The key of F major has long associations with nature and calm pastoral scenes. As flowers bloom and the pollen count soars, let’s finish out the week with four pieces in F major which evoke images of a springtime pasture:

Bach’s Pastorale in F Major

Historians believe that bagpipes may have predated ancient Rome. On hillsides in southern Italy and beyond, shepherds played Zampogna (Italian bagpipes). You can hear echoes of the Zampogna in J.S. Bach’s Pastorale in F Major, BWV 590, written for organ around 1720. The first movement features gently rolling triplets in 12/8 time. The melody rises above an extended drone with two-voice imitative counterpoint frequently joining in thirds. Three dance movements follow: an Allemande, Aria, and Gigue.

Helmut Walcha made this recording at the Church of Young Saint Peter Protestant in Strasbourg in 1970:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S8I4yCmsi38

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony

How delighted I will be to ramble for awhile through the bushes, woods, under trees, through grass, and around rocks. No one can love the country as much as I do. For surely woods, trees, and rocks produce the echo that man desires to hear.

-Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven’s symphonies are a strange study in moderation. The odd numbered symphonies (3, 5, 7, and 9) are heroic and epic in scale. The equally profound, but less well known, even numbered works (No. 4, 6, and 8) are more classical and introspective.

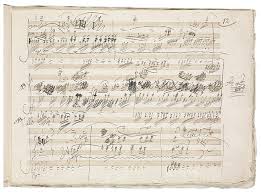

This sense of compositional “yin and yang” played out between 1804 and 1808 as Beethoven simultaneously sketched the powerful and ferocious Fifth Symphony and a radically contrasting work which encapsulated the poetry of nature: Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68. The two symphonies were published within weeks of each other in the spring of 1809 and were first performed on the same program. The Sixth Symphony was inscribed with the programmatically descriptive title, “Pastoral Symphony, or Recollections of Country Live.”

The Pastoral Symphony retreats into a bucolic world of bird calls, bubbling brooks and rustic folk dances. It’s music brimming with joy and gratitude at nature’s life-sustaining bounty. The outer movements are filled with open fifths, suggesting raw, natural elements and infinite possibility. (This is the first sound we hear at the beginning of the first movement). Motives develop over long periods of time with unbridled expansiveness (1:43). Listen to the multiple rhythmic layers in the strings beginning around the 5:35 mark. Also notice the prominence of the oboes with their pastoral connotations.

Here is Paavo Jarvi conducting the Bremen German Chamber Philharmonic:

[ordered_list style=”decimal”]

- Pleasant, Cheerful feelings awakened in a person on arriving in the country. Allegro ma non troppo 0:00

- Scene by the brook. Andante molto mosso 12:10

- Merry gathering of country folk. Allegro 23:48

- Thunderstorm. Allegro 28:51

- Shepherd’s Song. Happy and thankful feelings to the deity after the storm. Allegretto 32:20

[/ordered_list]

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Berlioz’s Scene in the Country

The third movement (Scene in the Country) of Hector Berlioz’s turbulent Symphony fantastique (1830) transports us to the quiet solitude of the pasture. In the opening and closing of the third movement, there’s a haunting sense that time is standing still. There’s also a spacial element: the dialogue between oboe and English horn evokes two distant shepherds. Listen for the idée fixe (the hero’s leitmotif which runs throughout the piece) at 8:17.

Here is an excerpt from Berloz’s program notes:

One evening in the countryside he hears two shepherds in the distance dialoguing with their ‘ranz des vaches‘; this pastoral duet, the setting, the gentle rustling of the trees in the wind, some causes for hope that he has recently conceived, all conspire to restore to his heart an unaccustomed feeling of calm and to give to his thoughts a happier colouring. He broods on his loneliness, and hopes that soon he will no longer be on his own … But what if she betrayed him! … This mingled hope and fear, these ideas of happiness, disturbed by dark premonitions, form the subject of the adagio. At the end one of the shepherds resumes his ‘ranz des vaches’; the other one no longer answers. Distant sound of thunder … solitude … silence …

This is the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Eliahu Inbal:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Blaník from Smetana’s Má vlast

Blaník is one of six symphonic poems that make up Czech composer Bedřich Smetana’s Má vlast (“My Homeland”). If you know any music from Má vlast, it’s probably The Moldau.

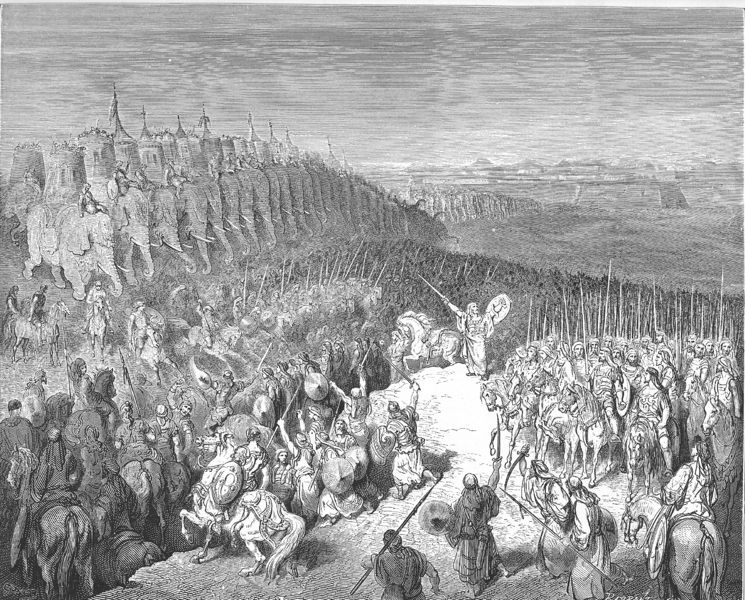

This music is inspired by a legend involving a huge army of knights asleep inside the mountain, Blaník. In the country’s darkest hour, when four hostile armies attack from all directions, it is believed that St Wenceslaus’ army will awaken and fight.

You can listen to the entire piece here. Here is the pastoral excerpt:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]