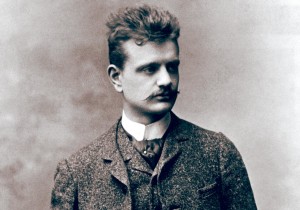

Jean Sibelius completed his Second Symphony in 1902 at a turbulent moment in Finnish history. Amid a surge of nationalism and renewed cultural unity, a growing movement called for Finnish independence from Russia. As Tsar Nicholas II sought to suppress Finnish language and culture, Sibelius’ music played an important role in the cultural reawakening of his homeland. Finlandia, the majestic nationalist hymn written in 1899 as a covert protest against Russian censorship, emerged as a defacto second Finnish National Anthem. A few years earlier, the Karelia Suite (1893) painted a mythic sound portrait and drew upon rough, backwoodsy Finnish folk elements. The same year, The Swan of Tuonela was inspired by the Kalevala, a collection of nineteenth century poetry which drew upon Finnish mythology. (The Swan of Tuonela was revised two years later and included in the Lemminkäinen Suite). Long dominated by Russia and Sweden, Finland would gain independence in 1917.

Some listeners have heard echoes of Finland’s struggle for independence in the Second Symphony. In 1902 the conductor Robert Kajanus, who championed Sibelius’ music and made the first recording of the Second Symphony in 1930 with the London Symphony Orchestra, wrote:

The effect of the andante is that of the most crushing protest against all the injustice which today threatens to take light from the sun (…) [The scherzo] depicts hurried preparation (…) [The finale] culminates in a triumphant closure which is capable of arousing in the listener a bright mood of consolation and optimism.

In 1998 conductor Osmo Vänskä suggested a similar, if more open-ended programmatic reading:

The second symphony is connected with our nation’s fight for independence, but it is also about the struggle, crisis and turning-point in the life of an individual. This is what makes it so touching.

But it’s possible, perhaps even likely, that Sibelius had none of this in mind when he was writing the Second Symphony. Despite the powerful nationalistic undertones of his smaller programmatic works, he seems to have approached the symphony as “pure music.” In his famous 1907 meeting with Gustav Mahler (in which Mahler declared, “A symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.”), Sibelius seemed to be interested in the pure, formal aspects of the symphony. During their philosophical discussion, Sibelius told Mahler that he

admired [the symphony’s] severity of style and the profound logic that created an inner connection between all the motifs…If we understood the world, we would realize that there is a logic of harmony underlying its manifold apparent dissonances.

We hear this sense of logical, organic development in the Second Symphony. It’s almost as if the invisible, creative powers of nature shaped and developed the work through the composer’s hand. The opening of the first movement emerges suddenly, even abruptly, out of silence. The first strong beats are literally silent rests, and the opening motive, set in 6/4 time, feels like a long upbeat leading to more silence. This ascending three note motive, first heard in the strings, is the seed from which the entire symphony grows. A few moments later, the woodwinds add the next layer of development: a buoyant, dancing countermelody. Quiet pizzicati lead into an exhilarating and terrifying accelerando. Then, listen to the sustained woodwind note which rises out of the string texture here. This single tone (a half step higher) becomes the thread which leads into the quietly shivering passage which follows.

That ascending motive in the opening is imprinted on the DNA of the entire symphony. It comes back slightly differently in the second movement, becomes a swirl of energy in the third movement, returns in the bridge to the final movement, and then becomes a triumphant proclamation in the opening of the final movement, the Symphony’s climax.

But let’s return to the silence of the opening. Sibelius was a composer who lifted music out of silence. He required hours of uninterrupted silence to work. In the final years of his life, he descended into a permanent creative silence, unable to compose and eventually destroying sketches of a stillborn Eighth Symphony. The Second Symphony is filled with unsettling moments which abruptly trail off into silence. It’s as if the music is unable to shake off the reality of its silent opening beats. One of these moments comes in the Nordic gloom of the second movement where, just as we seem to be reaching a climax, a brooding brass choral is interrupted by a series of pauses. When this music returns later in the movement, the silence is filled with strangely static woodwind chords. A moment later, one of the movement’s longest pauses delivers us into a hushed new sonic world. Barely emerging from the silence, strings are joined by a glassy, meandering woodwind line.

For all of its dramatic motion towards the climax of the final movement, Sibelius’ Second often seems to struggle with resolution. There are moments where the music can’t quite sum up what it’s trying to say, as if the titanic forces unleashed are too big to wrap your arms around fully (this passage from the second movement, for example). The first and second movements culminate in chords which seem slightly brusk, coming and going too soon. Even in the final two minutes of the symphony, there’s a sense of unresolved energy, as the music reaches increasingly higher, striving for an ultimate, unattainable goal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPd9znWgGLk

Recommended Recordings

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Osmo Vänskä 1997 recording (featured above) with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra at iTunes, Amazon.

- Vänskä is re-recording the Sibelius Symphonies with the Minnesota Orchestra. Find the new recording, released in 2012 at iTunes, Amazon.

- George Szell’s 1970 recording with the Cleveland Orchestra. This was his last recording with the orchestra.

- Leonard Bernstein’s performance with the Vienna Philharmonic.

- Gustavo Dudamel’s performance with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra

[/unordered_list]