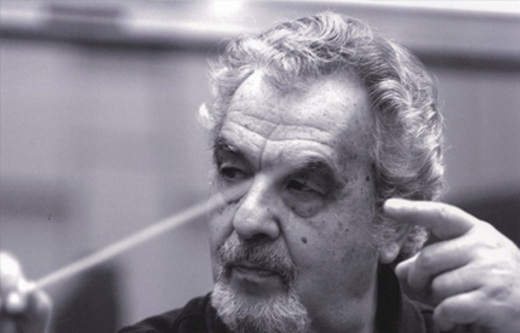

Austrian conductor and violinist Walter Weller passed away last Sunday at the age of 75. Weller was one of the last links to a Viennese musical tradition rooted in the nineteenth century.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Walter Weller joined the Vienna Philharmonic at the age of 17, eventually becoming one of its concertmasters. In addition, he performed as first violinist of the Weller Quartet. In 1966 he was asked to fill in on short notice for the conductor Karl Böhm. This launched a conducting career that included regular appearances at Vienna State Opera and Volksoper and principal conductor posts with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and the Scottish National Orchestra. In an article in Glasgow’s Herald Scotland, music critic Michael Tumelty said that Weller

had a seminal influence on the sound of [the RSNO] that extends to this day. He brought a depth and richness of sound that nobody else ever has.

Conductor Kenneth Woods offered this description in 2007.

Walter Weller leaves behind an extensive discography, ranging from music of Martinu and Suk to the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Prokofiev. Here is his 2004 recording of Mendelssohn’s overture, The Hebrides, Op. 26, “Fingal’s Cave” with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Throughout the overture, we hear the windswept mystery of the remote Scottish islands Mendelssohn visited around 1829…the play of light and shadow on the water and the rugged cliffs surround Fingal’s Cave. This sense of mystery remains unresolved in the final chords. Weller’s performance comes to life with fiery excitement and also with incredibly soft moments of introspection:

Here is Walter Weller’s 2006 recording with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra of Beethoven’s overture, The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43. The overture opened Beethoven’s 1801 ballet score.

Here is the final movement from Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony No. 1 from a 1975 recording with the London Symphony Orchestra. It’s hard to imagine a more exciting performance. Listen carefully to the little interjections throughout this joyful whirlwind of a movement:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-VzW2_Yr2hc

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]