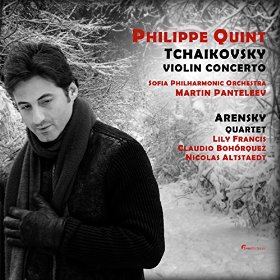

In September, Russian-American violinist Philippe Quint released a recording of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, accompanied by conductor Martin Panteleev and the Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra. If you already own a thousand recordings of the Tchaikovsky, there are good reasons to also include this CD in your collection. Quint offers a distinctive and introspective performance, which emphasizes a rounded, singing tone, even in the most difficult passages of the first movement’s cadenza. He also includes Tchaikovsky’s rarely heard original final movement.

In September, Russian-American violinist Philippe Quint released a recording of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, accompanied by conductor Martin Panteleev and the Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra. If you already own a thousand recordings of the Tchaikovsky, there are good reasons to also include this CD in your collection. Quint offers a distinctive and introspective performance, which emphasizes a rounded, singing tone, even in the most difficult passages of the first movement’s cadenza. He also includes Tchaikovsky’s rarely heard original final movement.

As Philippe Quint explains in this interview, Tchaikovsky originally dedicated the concerto to Leopold Auer, the legendary teacher of Mischa Elman, Jascha Heifetz and Nathan Milstein, among others. Auer considered the third movement to be “unviolinistic” and set the concerto aside. Tchaikovsky withdrew the dedication and rededicated the work to Adolph Brodsky, who gave an ill-fated premiere in Vienna on December 4, 1881. Leopold Auer later revised the final movement and this is the version we almost always hear performed.

Listen to Quint’s performance of the first and second movements and the standard Auer version of the third movement. Then compare it with Tchaikovsky’s original version of the final movement (below). The influence of ballet seems to be just below the surface in much of Tchaikovsky’s music. Throughout ballet scores like The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, and The Sleeping Beauty, Tchaikovsky often repeats short, symmetrical phrases. We hear a similar kind of repetition in the third movement of the Violin Concerto (1:01-1:09, for example). Auer condensed the score, cutting these repeated passages.

Arensky’s String Quartet No. 2

This recording also includes Anton Arensky’s String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, Op. 35 (1894). Arensky, a student of Rimsky-Korsakov and the teacher of Alexander Scriabin and Sergei Rachmaninov, dedicated the Quartet to the memory of Tchaikovsky. The second movement is a series of variations on a theme from Tchaikovsky’s Legend, No. 5 from 16 Songs for Children, Op. 54. Arensky’s Quartet features the unusual combination of violin, viola and two cellos. Here are the first, second and third movements.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]