The word “metamorphosis” signifies a transformation from an embryonic state to maturity.

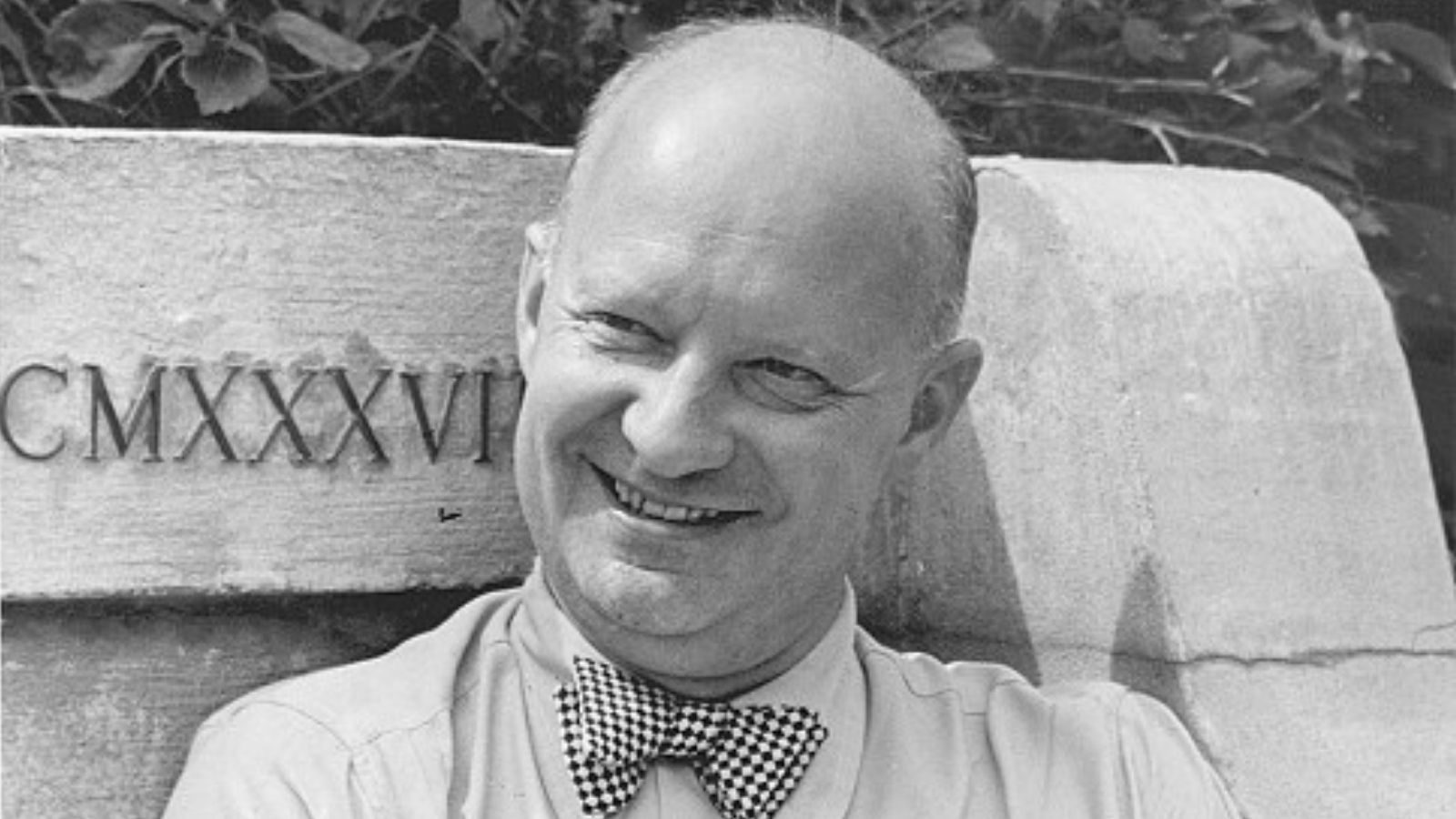

Symphonic Metamorphosis on Themes of Carl Maria von Weber by Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) employs this process. The four-movement orchestral work, completed in 1943, is based on obscure music by Weber, an innovative opera composer who is credited with expanding the size and dramatic scope of the orchestra at the dawn of the Romantic period. The themes, almost completely preserved, are drawn from four hand piano duets Hindemith played frequently with his wife. Dressed in new harmonic garb, the original themes become seeds for striking new music.

The genesis for the work came in early 1940. Hindemith had emigrated to the United States, having fled the Nazis, who branded his music “degenerate.” Russian choreographer Léonide Massine suggested that Hindemith compose a ballet based on themes by Weber. The two, who had collaborated two years earlier on Nobilissima visione, had artistic differences. Rather than adventurous new music, Massine wanted a simple re-orchestration of Weber. At the same time, Hindemith was taken aback by proposed sets and costumes based on the art of Salvador Dali. The abandoned ballet score was soon reborn as music for the concert hall.

Symphonic Metamorphosis begins with a sunny, exuberant Allegro in which the instrumental voices of the orchestra engage in a playful romp. In one passage (beginning at 3:03), the violas and upper woodwinds blend to suggest the mixture stop on a pipe organ (shimmering high-pitched overtones above the principal lower pitch). The same effect can be heard in Ravel’s Bolero.

The second movement, Scherzo (Turandot) comes from Weber’s incidental music to Schiller’s adaptation of Carlo Gozzi’s Turandot. It is the same story popularized by Puccini’s 1926 opera. The infectious theme, evocative of China and the orient, is introduced by the solo flute, and accompanied by dreamy chimes and a hushed string drone. Emerging in solo voices and groups of instruments, it is tossed around the orchestra. The distinct personas of the voices come alive in a colorful conversation. Just when we think the music is exhausted, the theme develops into the subject of a lively fugue. Hindemith, a noted teacher of composition and music theory, seems to be reveling in his knowledge of the instruments and his mastery of traditional forms.

The third movement (Andantino) unfolds as a simple melody filled with mystery and quiet longing. It begins as a musical conversation between the clarinet and bassoon. In the final section, the theme is embellished by a “dancing” flute obligato.

Beginning with a bold trombone “announcement,” the final movement is a spirited march, punctuated by drumbeats and noble horn calls. A grand instrumental tour de force, Symphonic Metamorphosis concludes with a sense of festive celebration.