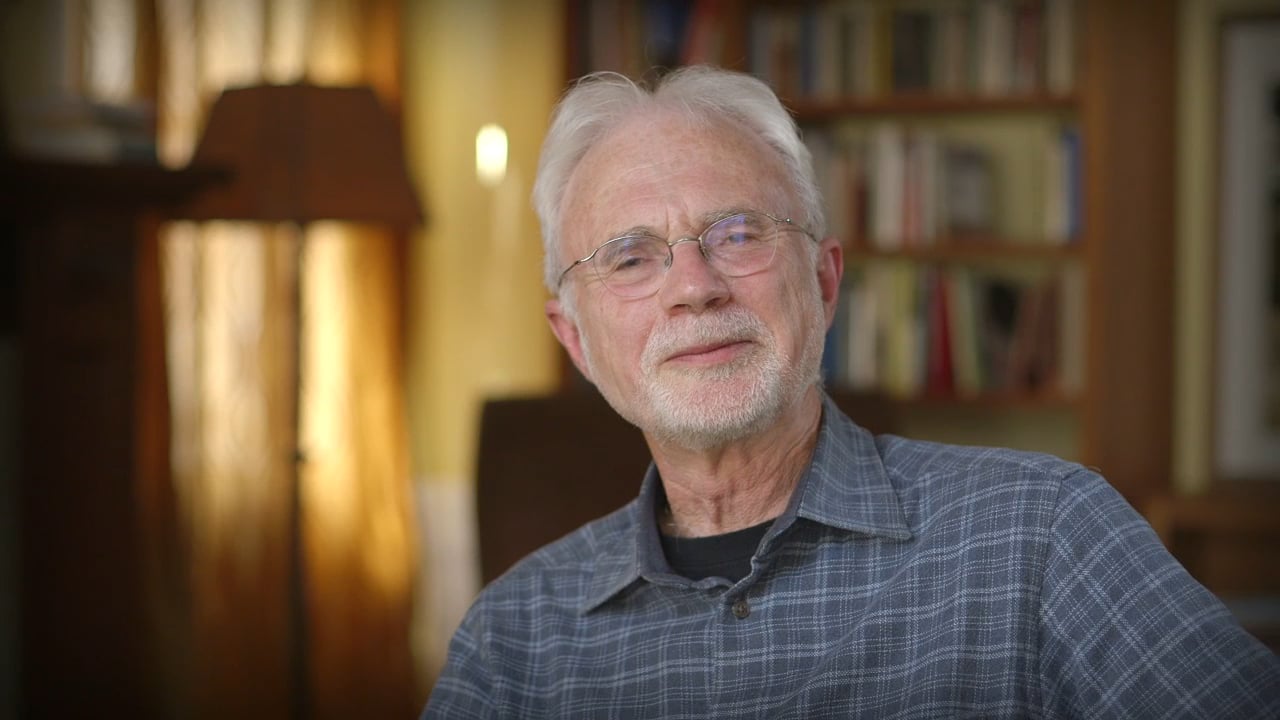

Today marks the 70th birthday of American composer John Adams. Adams may be the most publicly recognizable face of contemporary American music. More than any other living American composer, he seems to have inherited the mantle once held by Aaron Copland.

John Adams’ earliest music, like Phrygian Gates (1977) and Common Tones in Simple Time (1979), grew out of the pulse-based, pattern-oriented minimalism of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. But even these early works seem restless to move beyond pure minimalism into new directions. In the final movement of Grand Pianola Music (1982), repeating patterns suddenly give way to an outrageous blend of Beethovenian bravura and gospel music. Audiences at the premiere found the piece so shocking that it was booed. In Shaker Loops, we hear the hushed, shivering tremolos of Sibelius. The hazy Eros Piano flirts with jazzy impressionism. The Wound-Dresser is a haunting setting of Walt Whitman’s Civil War-era poem.

Several of John Adams’ works have been inspired by dream images. A dream involving a supertanker lifting off like a rocket from San Francisco Bay inspired the stern, pounding, opening minor chords of Harmonielehre (1985). It’s a piece which summons the ghosts of Arnold Schoenberg, Mahler, and Sibelius and draws upon rich orchestral color. In the virtuosic Chamber Symphony (1992), Schoenberg’s serialism blends, irreverently, with cartoon music. Adams’ operas, which include Nixon in China (1987), The Death of Klinghoffer (1991), and Doctor Atomic (2005), treat topics as unlikely as foreign diplomacy, terrorism, and nuclear physics as a mythic backdrop.

We’ll listen to a few of my favorite John Adams pieces over the next few months. Today, let’s start with Fearful Symmetries, a piece described by Adams as “an industrial-strength boogie.” In a recent post, I mentioned Beethoven’s sense of compositional moderation, alternating between the big, heroic, odd-numbered symphonies and their more classical, even-numbered counterparts. John Adams has commented frequently on a similar alternation between “serious” pieces and “trickster” pieces. Fearful Symmetries falls into the second category. It’s a piece filled with characters and multiple allusions. The jazz of Ellington and Gershwin collide with Stravinsky and the endless arpeggios of Philip Glass. Pop rock and the garish sounds of the double-manual Yamaha Electone synthesizer blend with a “lounge lizard” saxophone quartet. In an interview with Edward Strickland, Adams suggested that the piece evokes images of a silent film, as in “the girl tied to the railroad tracks.”

Fearful Symmetries was written in the spring of 1988, immediately following Nixon in China. Adams might have been trying to move beyond his newly completed opera but, to his surprise, the “sounds” of Nixon began to emerge. The instrumentation is almost identical to the opera’s pit orchestra. Adams describes it as “a kind of mutated big band, heavy on brass, winds, synthesizer and saxophones.” In his 2008 autobiography, Hallelujah Junction: Composing an American Life, John Adams writes,

The title phrase comes from the poem, “The Tyger” by William Blake. It was not so much the content of Blake’s poem that stirred me but rather the key phrase, “fearful symmetries,” that I was drawn to. As I worked on the piece, I found that ideas were coming to me in almost maddeningly symmetrical packages of four-, eight-, and sixteen-bar harmonic units. This was not far removed from the back-and-forth harmonic alternations of “On the Dominant Divide,” the final movement of Grand Pianola Music. Rather than try to deconstruct the obviousness of these harmonic structures, I did the opposite: I amplified their predictability and in so doing ended up composing an insistent pulse-driven juggernaut of a piece that has continued to prove useful to scores of choreographers and dancers.

As you listen to Fearful Symmetries, enjoy the visceral sense of pulse and the continuous rhythmic groove. Notice all of the competing, sometimes conflicting, currents which swirl around the pulse. Consider the overall shape of the piece as it moves through a series of adventures. For me, part of the fun of Fearful Symmetries is the way it always keeps us off balance. A cast of outrageous, comic characters emerge. At the same time, there’s a slightly ominous undertone to the continuously chugging, unending pulse. Listen and then share your experience in the thread below.