Music has the ability to unleash mysterious powers which transcend the literal. I was reminded of this recently, as I listened to George Gershwin’s ebullient song, Of Thee I Sing, featured in Monday’s post. It’s the title song of one of the Broadway musical theater’s most zany political satires. Within the show, the premise of the song is delightfully ridiculous: It’s the campaign song of a goofy presidential candidate who’s running on a “love” platform. It’s the furthest thing from serious or “profound.” But recently, as I was listening to this lighthearted song, I couldn’t help but feel a strange undercurrent of nostalgia, sadness, and a complex, multidimensional mix of other emotions. I found myself drawn to the mellow, lamenting tones of the saxophones, which, in that orchestration, hold court like a group of soulful, old guests. For me, it’s not the first time that “happy” music has had this effect. For example, Mahler’s music is full of these indescribable ironies. Perhaps in this case, it’s a testament to Gershwin’s ability to turn a simple melody into an eternally expressive work of art. But more broadly, it speaks to something fundamental about music itself.

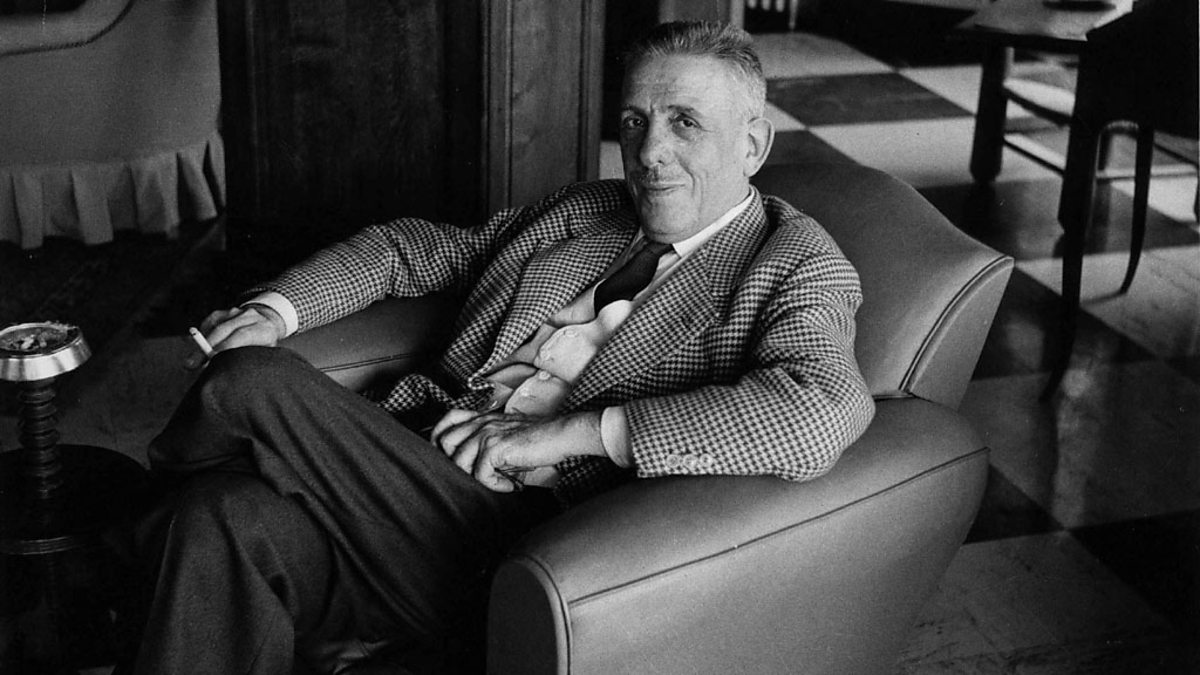

In a recent post at his blog, A View from the Podium, conductor Kenneth Woods describes a similar experience involving the music of French composer Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)- specifically, the witty, neoclassical 1924 ballet score, Les biches. Woods writes,

Poulenc’s frothy, frivolous and rather sexy ballet Les biches does not seem, at first glance, to be the sort of piece to make a hardened muso well up with emotion, but it had just that effect on me about a week ago as I listened to it for the first time in ages…On the other hand, few composers could ever squeeze as much poignancy into a few notes as Francis Poulenc. He had a genius for distilling rich, powerful and complex emotions into simple, economical and seemingly familiar musical gestures- I sometimes think of him like a French Janacek for his ability to make 2 or 3 chords or a tiny turn of phrase bring a tear to your eye. And Les biches, playfully raunchy as it is, is not without its moments of deep feeling.

In the same post, Woods mentions the Cavatina second movement of Poulenc’s Sonata for Cello and Piano. Listen to the piano’s serenely floating opening chords and you’ll hear the expressive power of simplicity. As the second movement unfolds it explores more intense territory, although often within a dreamy, veiled context which seems uniquely French. But at the end of the movement, we suddenly find ourselves back at the simple power of those glistening opening chords.

There are other extraordinary moments throughout this piece. For example, listen to the amazing harmonic shifts which occur in this passage towards the first movement (Allegro – Tempo di Marcia). Enjoy the vivacious frivolity of the third movement (Ballabile) which ends with the musical equivalent of a playful wink. And listen to the passionate dialogue between piano and cello that takes place in the final movement.

Poulenc first sketched this work in 1940, but it wasn’t finished until 1948, well after the Second World War. It’s music which leaves behind the excesses of Romanticism and the horrors of war in favor of sparkling neoclassicism. Here is the complete Cello Sonata, from a 2008 recording by cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras and pianist Alexandre Tharaud:

Kenneth Woods concludes with this thoughtful ode to the music of Poulenc:

Poulenc’s music is full of an intoxicating, almost desperate sense of longing, and real, aching nostalgia, juxtaposed with the most direct and unfiltered outbursts of childlike pure joy. “Joie de vivre” is a far more beautiful expression than any of its English translations, and to me, it points up the difference between mere happiness and true “joy of life.” Life is not always happy. It is full of sorrow, loss, disappointment, loneliness, terror and fear, to express, in true musical Technicolor glory as Poulenc does, joy in life, of life, is to find joy in the full mix of happiness and sorrow, delight and disappointment that we all must ultimately experience in the fullness of our lives. And so in an age where pre-packaged consumerist instant gratification and plastic instant “happiness” tries to paper over the pain of social isolation, personal hopelessness and great injustice, where autotune anthems try to drown out an inner soundtrack of utter despair, vive la joie de vivre, vive la frivolité.