Although they lived in Vienna as contemporaries, it is unclear if Schubert and Beethoven ever met.

The two composers shared a mutual respect, but in many ways they were polar opposites. While Beethoven dazzled audiences as a revolutionary giant of the symphony, during his lifetime, Schubert was known almost exclusively for his songs. Publishers failed to take interest in Schubert’s instrumental works, and many, such as the “Great” C Major Symphony No. 9, were heard publicly only years later.

As composers, Beethoven and Schubert approached music differently. Beethoven’s music unfolds with the development of dynamic motivic kernels. It is raw, fiery, and all-conquering. In contrast, Schubert’s music inhabits a more dreamy, introspective world melody. Rather than grab us by the collar, it invites us in. As violinist Mark Steinberg writes, Schubert’s music evokes “the glow of memories of an unredeemable idyllic past or in recognition of a paradise beyond reach.” At times, joy and melancholy seem to exist simultaneously in the music of Schubert, who once stated, “When I attempted to sing of love, it turned to pain. And when I tried to sing of sorrow, it turned to love.”

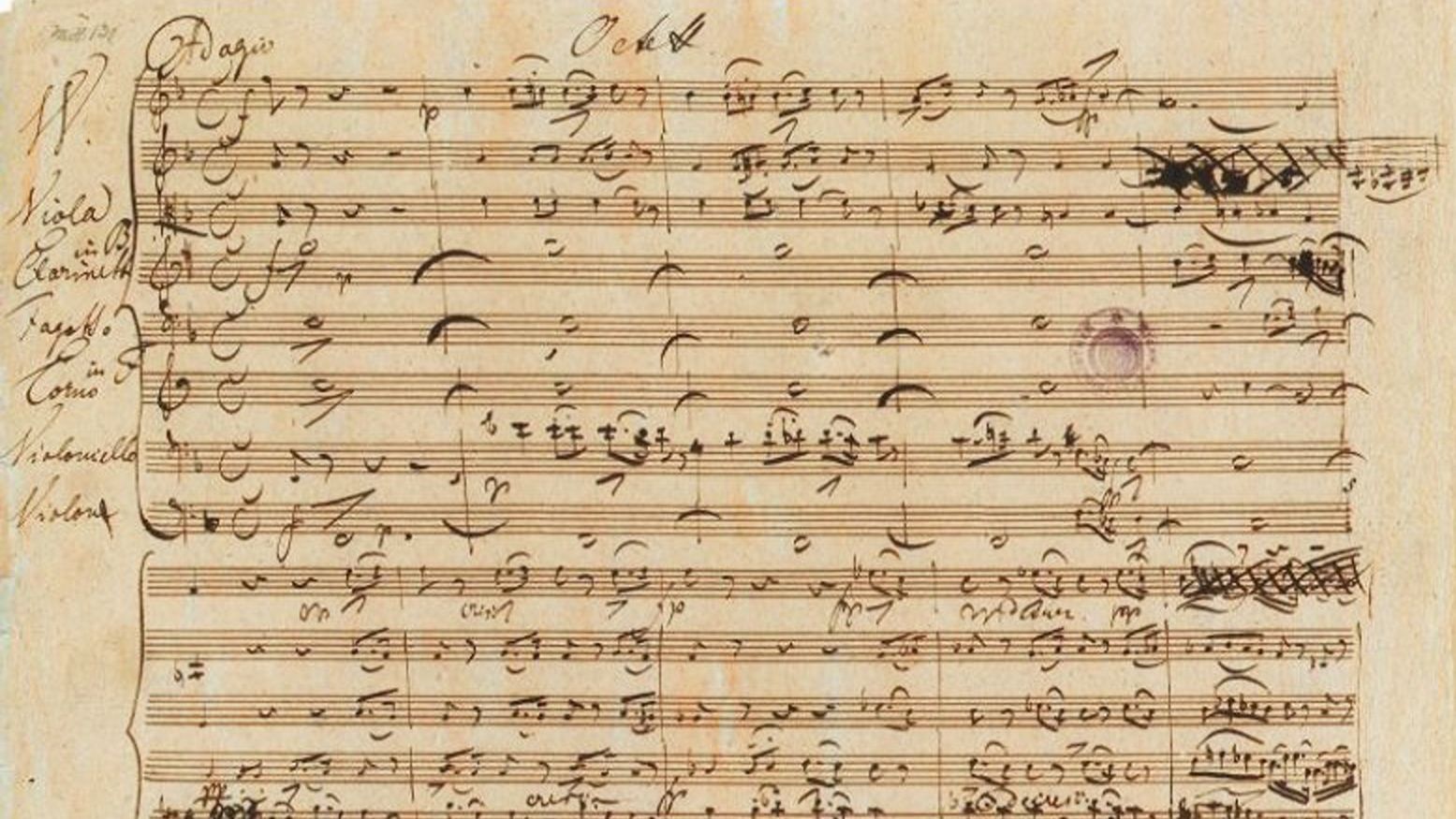

Indirectly, Beethoven was the impetus behind Schubert’s Octet in F Major, D. 803. The work was commissioned by Ferdinand Troyer, a renowned clarinetist who was employed by Archduke Rudolf, one of Beethoven’s great patrons. Troyer requested a piece similar to Beethoven’s Septet, Op. 20, composed 24 years earlier. Schubert obliged with a six-movement work of similar structure. (Both pieces pay homage to the 18th century serenade, or divertimento). Schubert scored the Octet for clarinet, bassoon, horn, two violins, viola, cello, and double bass. (The addition of a second violin is the only modification of the instrumentation of Beethoven’s Septet).

Schubert completed the Octet on March 1, 1824 during the same period as the Rosamunde and Death and the Maiden string quartets. The feverish pace at which the composer worked was observed by his friend, Moritz von Schwind, who wrote, “When visiting him during the day he gives his greetings, asks how everything is, and when asked how things go with him, he responds ‘fine,’ without interrupting his writing. So one leaves.” The Octet received a private performance in April of 1824, led by violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, and including many of the musicians who had premiered Beethoven’s Septet.

The Octet’s outer movements open with slow introductions. The first movement (Adagio – Allegro – Più allegro) begins with a unison F call to order. Spirited dotted rhythms pervade the movement, and the seed for this motif can be heard in the second measure. Throughout the mysteriously wandering introduction, the rhythm mirrors that of the funeral march of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, completed in 1812. The sun emerges with the arrival of the exuberant Allegro section, and an exuberant and virtuosic musical conversation unfolds in which the distinct persona of each instrumental voice comes into focus. A nostalgic statement by the horn brings the movement to a close.

The second movement is marked Adagio, or Andante un poco mosso, depending on the edition of music used. It begins with an expansive and serenely beautiful 12-bar melody, played by the clarinet, and accompanied by rolling lines in the strings. Soon, the first violin joins the clarinet, taking up the melody in a tender duet. As the movement continues, we enter a drama filled with joy, sorrow, mystery, and transcendence. We are transported through sudden modulations to remote keys, a device found throughout Schubert’s music. In the final moments, the serenity is shattered by a sforzando pizzicato F which erupts in the low registers of the bass and cello. The remaining music is shrouded in tragedy.

The third movement (Allegro vivace – Trio – Allegro vivace) is a jubilant, bucolic scherzo. It is filled with the adventure of a hunting party. In one passage, a rustic drone bass line emerges. The scherzo’s peasant dance gives way to a Ländler trio section, propelled forward by a walking bass line in the cello.

The fourth movement (Andante – variations. Un poco più mosso – Più lento) unfolds as a set of seven far-reaching variations on a charming melody. The theme was taken from the comic Singspiel Die Freunde von Salamanka (“The Friends from Salamanca”), which Schubert wrote when he was 18, and which remained unperformed during his lifetime.

The fifth movement (Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio – Menuetto – Coda) revives the minuet, a form which was already outdated at the time. It is filled with graceful motion and elegance. The trio section returns to the carefree, rustic world of the Ländler.

The cheerful final strains of the minuet are soon a distant memory as the opening of the final movement (Andante molto – Allegro – Andante molto – Allegro molto) plunges us into pure terror. It begins as a low, ghostly rumble in the cello and bass. The trembling grows and erupts in a cry of anguish. This is a quote of Schubert’s song, Die Götter Griechenlands, D. 677 (“The Gods of Greece”), the text of which centers around loss, mourning, and the restorative power of music (“the magic land of song”). The motif also is strikingly similar to the Trio section of the third movement of Beethoven’s Seventh symphony. This shocking introduction suggests an almost operatic sense of drama. With the arrival of the Allegro, we enter “the magic land of song.” Only briefly do the ghosts resurface. The joyful celebratory march seems to laugh in their face, and drive them away. In one twice recurring passage, a virtuosic and comic game of imitation takes place between the first violin and clarinet. The coda section surges to a euphoric conclusion

This performance, recorded at the 2015 International Chamber Music Festival in Utrecht, features Janine Jansen (violin I), Gregory Ahss (violin II), Nimrod Guez (viola), Nicolas Altstaedt (cello), Rick Stotijn (double bass), Andreas Ottensamer (clarinet), Fredrik Ekdahl (bassoon) and Radek Baborák (horn):

Five Great Recordings

- Gidon Kremer, Isabelle van Keulen, Tabea Zimmermann, David Geringas, Alois Posch, Eduard Brunner, Radovan Vlatkovic, Klaus Thunemann

- Camerata Freden

- Academy of St Martin in the Fields

- Melos Ensemble

- Mullova Ensemble

Featured Image: Schubert’s autograph of the Octet in F (D. 803)