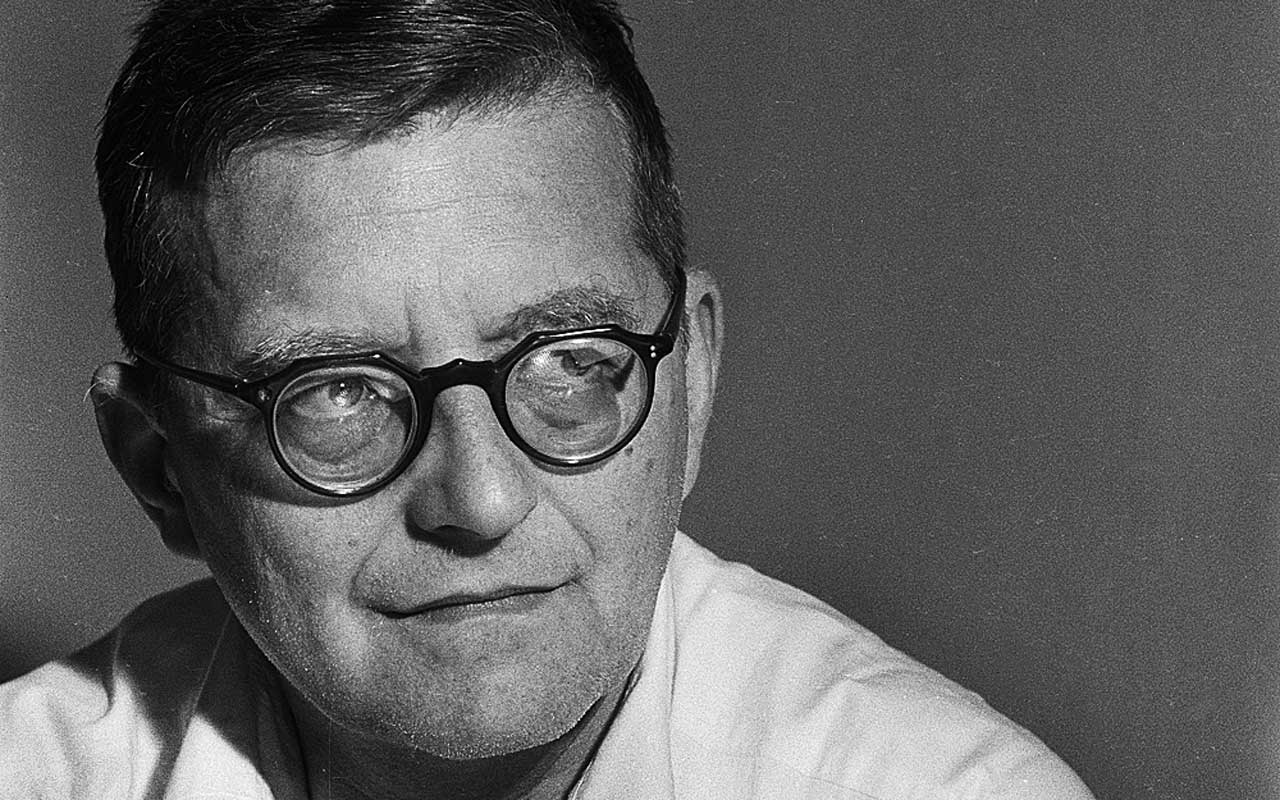

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Sixth Symphony is an outlier…a rule breaker. At first glance, its form seems startlingly unbalanced and arbitrary. It’s cast in three movements rather than four: A slow, darkly ominous first movement followed by two short, almost frivolous scherzos. The result is schizophrenic and unsettling…a jarring juxtaposition of starkly contrasting moods. It’s the quintessential anti-heroic symphony, shattering our hopes and expectations. By the time we reach the final movement, a simultaneously grotesque and giddy circus march, we’ve given up on the kind of transcendent journey from darkness to light we experience in Beethoven’s Fifth, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth, or even Shostakovich’s Fifth. This music has something much different to say.

Shostakovich’s music cannot be separated from its time: the repressive political environment under Stalin, and the grim drumbeats of war. Music which was not openly patriotic, not easily appreciated by the masses, and not rooted in the literal, such as Communist ideology, was subject to banning by the Soviet Composers Union. Following charges of “affronts to decency and comprehensibility” after the premiere of his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the more conservative and approachable Fifth Symphony put Shostakovich back in good standing with the authorities. He promised that his Sixth Symphony would be a musical monument to Lenin, a massive choral symphony on the order of Beethoven’s Ninth:

I have set myself a task fraught with tremendous responsibility, to express in sound the immortal image of Lenin as a great son of the Russian people and as a leader of the masses. I have received numerous letters from all over the Soviet Union with regard to my future symphony. The most important advice contained therein was to make considerable use of musical folklore.

But when the Sixth Symphony was first performed in Leningrad in November, 1939, there was no chorus and no audible reference to Lenin. Amid speculation regarding what the symphony was “about,” Shostakovich gave this politically expedient non-answer to the Soviet press:

The musical character of the Sixth Symphony will differ from the mood and emotional tone of the Fifth Symphony, in which moments of tragedy and tension were characteristic. In my latest symphony, music of a contemplative and lyrical order predominates. I wanted to convey in it the moods of spring, joy, youth.

The “joy” of the final two movements feels empty and sardonic, especially after the first movement’s unresolved gloom. As conductor Mark Wigglesworth points out:

In the Sixth Symphony, Shostakovich wanted to express an illogical and contradictory world and so chose a form that is both those things. The upbeat nature of the two scherzos should sound hollow, the phoney heartlessness of large groups of people. It is daylight, and false. Stalin had asked for light and boisterous finales. Shostakovich responded with such extreme agreement that he was again able to satisfy the conflicting demands of his mentor and his conscience. The writer Ian MacDonald puts it perfectly: ‘If you want light music, you are going to get it – and with vengeance.’ At the most bombastic moments of the finale, a thought must be spared for the pain of the first movement. The contrast makes for uncomfortable listening. You feel almost guilty at being carried away, however briefly, by the joie de vivre of the finale. It was a guilt that many did not want to own up to when it came to supporting Stalin.

The spirit of Mahler emerges throughout the Sixth Symphony, from the occasional edgy sounds of stopped horns and screaming clarinets, to the chamber music-like parade of individual instrumental voices, to the bubbling up of strange psychological references. (In the Sixth Symphony’s final movement, there’s a brief, bizarre nod to Rossini’s William Tell Overture, a reference which re-emerges in the Fifteenth Symphony). As with much of Mahler’s music, the Sixth Symphony is filled with uncomfortable ironies. We often don’t know quite how to interpret this music. Is it joyful or mockingly sarcastic, or both? Before starting the Sixth, Shostakovich created a piano transcription of the haunting Adagio first movement of Mahler’s unfinished Tenth Symphony. As with Shostakovich’s Sixth, Mahler’s final symphonies radically alter the standard ordering of symphonic movements. In both Mahler and Shostakovich, there’s a sense that the drama is shaping the form.

The Sixth Symphony is also filled with brief echoes and fragments of the Fifth. The Fifth Symphony’s desperate, rising scale lines reappear in the Sixth Symphony in the opening of the first movement, and again in this later passage. Throughout the first movement, there’s a feeling of relentlessly building tension…the sense of seething frustration just below the surface. Then, there’s the passage in the final movement when the DSCH motive (Shostakovich’s initials translated into pitches using German musical notation) appears. It’s a musical cryptogram which is practically the “idea fixe” of Shostakovich’s compositional output. At one moment in the final movement (a few seconds into this excerpt), a soaring trumpet statement seems to be trying to pull us back to the forced exultation of the final bars of the Fifth Symphony. But this time there won’t be even an attempt at a triumphant ending…only a whirling, grotesque circus.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ABll94SYXvM

Recordings

- Kirill Kondrashin and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra (featured above): iTunes, Amazon.

- Carlos Miguel Prieto and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra in a live performance

- Mariss Jansons and the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra’s 1991 recording

- Dmitri Kitayenko and the Gürzenich Orchestra’s 2008 recording

- Leonard Bernstein offers a brief discussion of Shostakovich’s Sixth Symphony