“Is the conductor really doing anything, or is he/she just for show? I mean, couldn’t you guys play without someone standing on a podium and waving their arms?”

This is the unexpected question once posed to me by an audience member after a Richmond Symphony concert. It’s pretty much the same question that comes up in this classic comedy bit from Seinfeld. Recent news that the Dallas Symphony Orchestra paid outgoing Music Director Jaap van Zweden a cool, record-shattering $5,110,538 last year will probably shock anyone entertaining the notion that conductors are mere figure heads. And while it’s debatable whether any conductor is worth that much money, the vital importance of the conductor is indisputable.

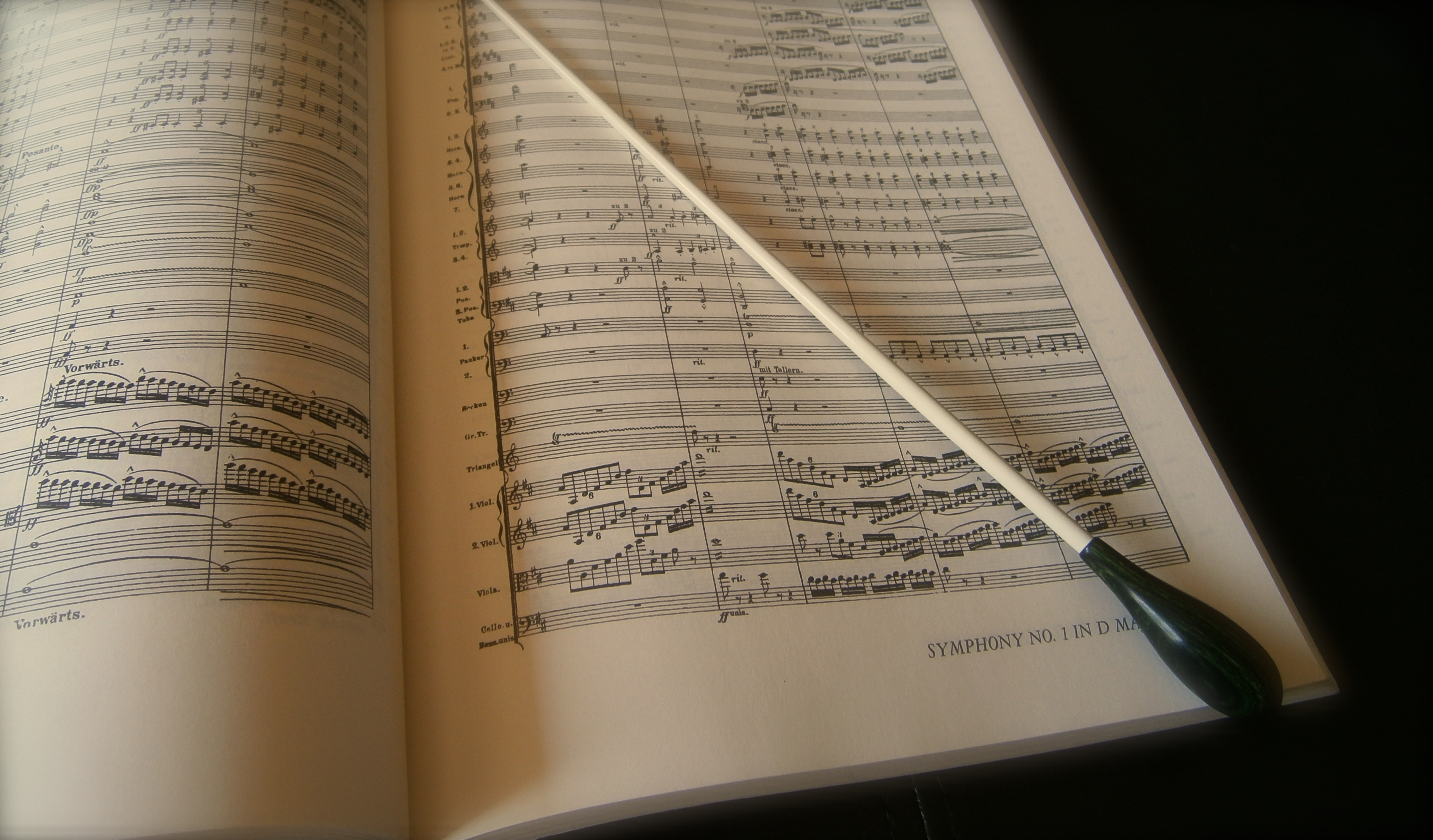

First, conductors are essential on a technical level. While earlier, smaller-scaled works, like a Mozart Symphony, can be played successfully without a conductor (the concertmaster becomes the leader and the interaction between musicians resembles chamber music), most orchestras would never be able to survive the fluctuating tempos of a Mahler symphony, or the complex meter changes of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, without the unifying force of a conductor’s beat pattern. The motion of the tip of the baton from one point in the air to another becomes a universal language signifying the rhythmic meter of the music. Cues give musicians confidence that they’re coming in at the right time.

But the technical, traffic cop element of conducting is only the beginning. Conductors have to be both students and teachers. They must know every intimate detail of the score and how it all fits together. Good ears, and the ability to distinguish the smallest detail buried under mounds of dense counterpoint, are required. Conductors hear the music in their mind a split second before it’s played, while simultaneously listening to what is being played. Great conductors have a compelling sense of how a given piece should sound- everything from tempo, to volume, to style. In rehearsals, through gestures and eye contact, they inspire the orchestra to share their vision. Orchestra musicians, who play the same pieces multiple times, often carry preconceived ideas about the music. There’s nothing more exciting than discovering a new way to hear an old piece.

Finally, there’s the mystical, ineffable aspect of conducting- the reality that the sound of an orchestra subtly changes depending on who’s on the podium. It’s not something that can be faked or calculated. There’s no room for ego. No great conductor practices in front of a mirror or thinks about how they look during a performance. A performance truly comes alive when conductor and orchestra enter into a magical sense of give and take, allowing the music to unfold in a way in which everyone becomes the audience.

The greatest conductors know when to help and when to get out of the way. In this Vienna Philharmonic performance of the final movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 88, Leonard Bernstein puts this into practice. This clip brings to mind Gustav Mahler’s quote, “My arms are not absolutely necessary when I conduct! If I weren’t obliged to wear glasses, I would conduct with my eyes.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oU0Ubs2KYUI

Additional Links

- The Art of Conducting – Great Conductors of the Past -fascinating video clips and commentary featuring legendary conductors of the past

- The Art of Conducting – Legendary Conductors of a Golden Era

- Gerard Schwarz gives a Conducting Lesson

- Kenneth Woods: How to rehearse an ensemble

- London Symphony Orchestra conducting masterclass with Valery Gergiev.

- Bernard Haitink and the Importance of Eye Contact

- Great conductors in rehearsal

Hi Timothy,

Lot of thanks for this incredible video showing Lenny conducting the last movement of Haydn’s 88th with the VPO. From my meaning only very great conductors such like Lenny can successfully do that, that’s probably mainly due to their exceptional aura. Other famous examples: Fritz Reiner with the Chicago and Yevgeni Mravinsky with Leningrad Philharmonic.

Friendly.

Claude

Sir Antonio Pappano conducting the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in a program of Rossini, Beethoven and Saint-Saëns was a magical evening to treasure. In April, 2016, in Paris at the Philharmonie de Paris I had the good fortune to attend this performance. It was the anticipation of Hélène Grimaud, piano in Beethoven’s Concerto No. 4, that was the catalyst. However, Sir Antonio and the orchestra in their interpretation of Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 3 with organ was an experience of a lifetime.