Even in the case of a popular song, harmony can be as important as melody. For example, listen to the harmonic surprise at the beginning of Richard Rodgers’ If I Loved You from Act 1 of the groundbreaking 1945 musical, Carousel. On the word, “loved,” a sudden, poignant diminished seventh chord takes us to a completely different world. This one melancholy chord tells us everything we need to know about what might lie ahead in the drama. It reminds us that emotions are complex and multidimensional and love and tragedy are all-too-often connected. The rich darkness of this harmony quickly subsides with the next chord, but somehow it stays in our ears for the rest of the song. Listen to the entire duet and you’ll hear that this is one of many luscious harmonic shifts in If I Loved You. And this is so much more than just a song. It’s an extended dramatic sequence unlike anything on the Broadway stage up until this point- an entire scene which unfolds through music and ties us intimately to the characters.

A few years later, in the score of South Pacific, Rodgers used the same chord in Bali Ha’i. Here, it coveys something exotic, bordering on mystical. Listen to I Wish I Were in Love Again, from the 1937 musical comedy Babes in Arms, and you’ll hear Rodgers flirting with the same harmony in a less dramatic context. This song, with its dizzying alternations between major and diminished chords, comes from his earlier, jazzier days with lyricist Lorenz Hart.

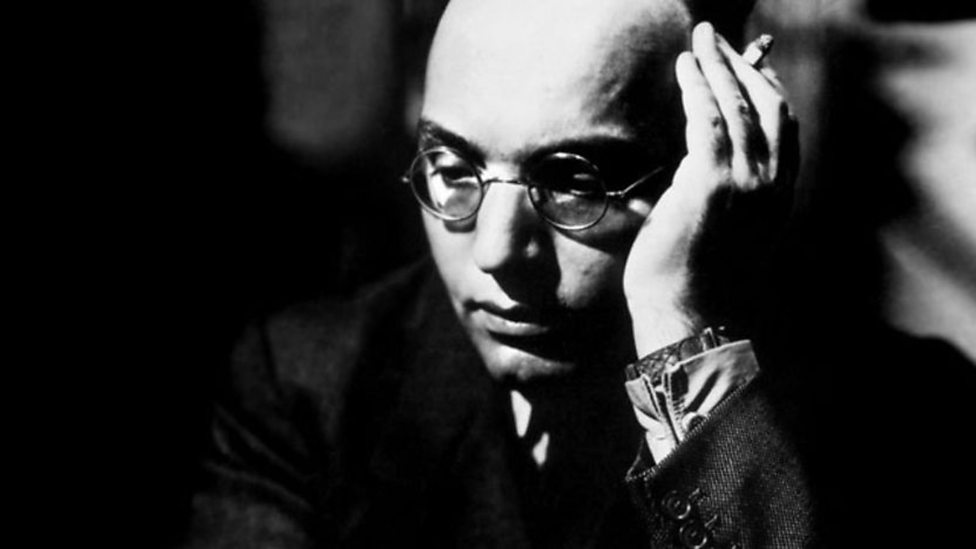

Which brings us to Kurt Weill’s September Song, written for the 1938 allegorical Broadway comedy, Knickerbocker Holiday. Throughout September Song, we hear the same kind of melancholy harmonic shifts. Maxwell Anderson’s lyrics remind us that life, like the turn of the seasons, is a cycle of birth and death:

Weill and Anderson wrote September Song in a matter of hours after Walter Huston requested that he should have one solo song in Knickerbocker Holiday. The song later became a standard, with performances by Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and even Lou Reed. As is common with popular song covers, these adaptations stripped the original harmony and became vehicles for the unique expressive capabilities of these performers. (Richard Rodgers reportedly hated many jazz adaptations of his songs). In its original form, with Walter Huston’s limited vocal ability, it’s the rich details of the song, itself, which take center stage.

Thank you, Timothy, for this interesting and lovely article on two of my favorite composers, Rodgers and Weill!

I would like to respectfully add Lotte Lenya’s interpretation of her husband’s memorable “September Song.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdc4oBnu_fw

Thank you, Mary!

Recently found your blog…keep the songs and works coming…it’s lovely to find someone who has the knowledge to do this and who wants to share with elderly folk like me (76)…love the takes on September Song…will share with my baritone…many thanks…Rosemary, Melbourne Australia

Thank you for your kind words, Rosemary. I’m glad you found the blog! Best wishes, Tim