Mahler, Schoenberg, Sibelius, Debussy, Ives, and other voices from the past emerge throughout the music of John Adams like fleeting ghosts. These voices are present in Adams’ towering neo-minimalist, neo-romantic symphony, Harmonielehre. They can also be heard in Slonimsky’s Earbox, the composer’s brief 1995 tone poem, premiered by Kent Nagano and the Manchester, UK-based Hallé Orchestra on the occasion of the September, 1996 opening of Bridgewater Hall.

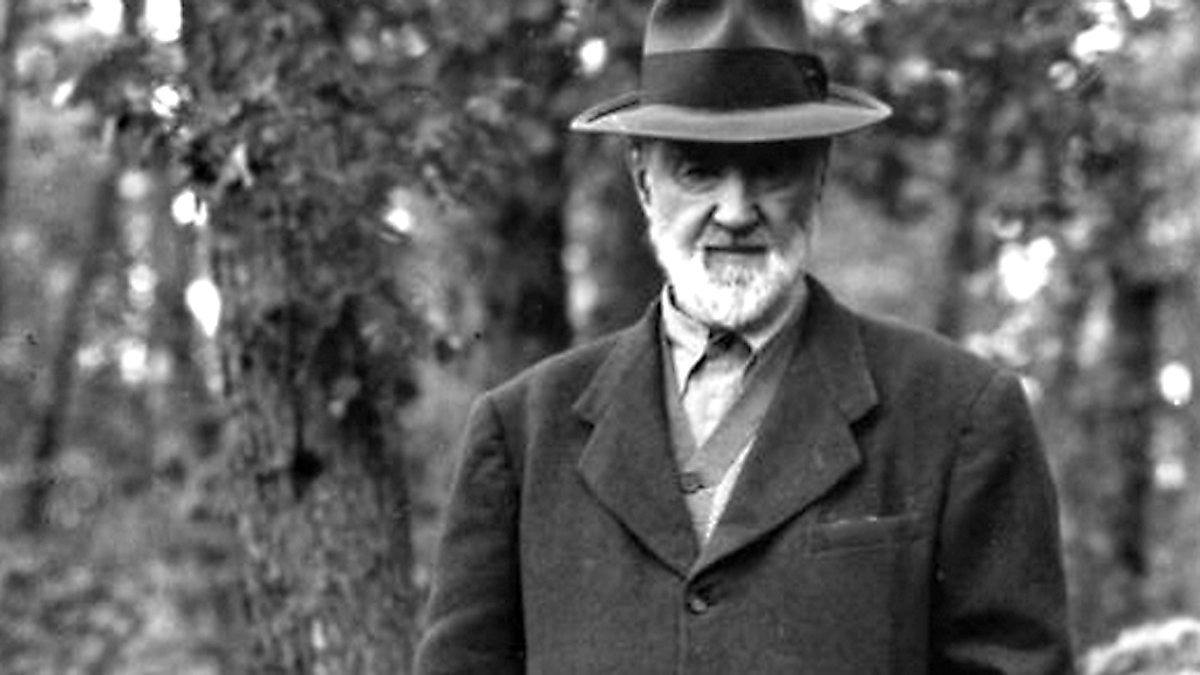

The title refers to Nicolas Slonimsky (1894-1995), the Russian-born American conductor, composer, musical theorist, and author. John Adams became aquatinted with this musical Renaissance man in his final years. The piece, with its cleverly-coined “Earbox” title, was written as a tribute to the man who enjoyed the semantic exercises of lexicography. Slonimsky’s Earbox is an exuberant and virtuosic celebration of the modal scales which are found in Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns. You’ll hear the influence of the equally modal opening of Stravinsky’s orchestral poem, Le chant du rossignol (“The Song of the Nightingale”), with its bright splashes of sound. Adams writes,

The model for this piece was the exploding first few moments of Stravinsky’s symphonic poem, Le Chant du Rossignol (The Song of the Nightengale). The way Stravinsky’s orchestra bursts out in a brilliant eruption of colors, shapes and sounds. What also attracted me was Stravinsky’s use of modal scales, a practice doubtless influenced by his Russian roots but which he abandoned soon after. I have long thought that the Russians–not only Stravinsky but composers like Scriabin and Tcherepnin–had begun something very important in their use of modal scales and harmonies, a direction that unfortunately was overwhelmed by more prestigous practices such as Neoclassicism and Serialism.

…Slonimsky was a character of mind-boggling abilities. He had a completey eidetic memory and could recall with absolute precision the smallest detail of something he’d read forty years before. He lived to be over a hundred, and his century spanned Czarist St. Petersburg where he was educated as a child to Santa Monica, California, where he lived into the 1990’s and where I’d come to know him. His autobiography, “Perfect Pitch”, stands alongside Berlioz’s memoirs as one of the few genuinely original literary works about music.

All of this is interesting. But for today, I want to focus on one haunting passage in Slonimsky’s Earbox in which a fragment of Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question emerges and then, just as quickly, evaporates. We get only the shortest glimpse of The Unanswered Question‘s timeless string choral, surfacing out of a vast, musical stream of consciousness. It’s there and then it’s gone, like a hazy, ephemeral image in a dream. Listen to Slonimsky’s Earbox and see if you can hear this musical “ghost”:

Did you hear the Ives with its distinctive, shifting passing tone in the bass right around the piece’s Golden Mean? It’s a brief moment of mystery and introspection in what is otherwise an exhilarating romp.

There is another interesting and fleeting reference to Ives’ The Unanswered Question in the late Oliver Knussen’s opera, Where the Wild Things Are:

In his lecture, The Twentieth Century Crisis, from the Norton series, The Unanswered Question, Leonard Bernstein discusses the central position Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question occupies in twentieth century music. Let’s finish up by listening to this famous piece, written by Ives, the adventurous New England Yankee, in 1906. When listening to this music, we often assume we know which voice is asking the question and which is unable to answer, but how can we really be sure? Consider this question and try listening to Ives’ famous, cosmic dialogue with new ears: