They’ve been called, “the most complex and artistically successful failed job application in recorded history.”

300 years after their composition, J.S. Bach’s six monumental “Brandenburg” Concertos are regarded as some of the greatest and most groundbreaking works of the Baroque period. But surprisingly, they came about as a result of seemingly practical, even mundane concerns.

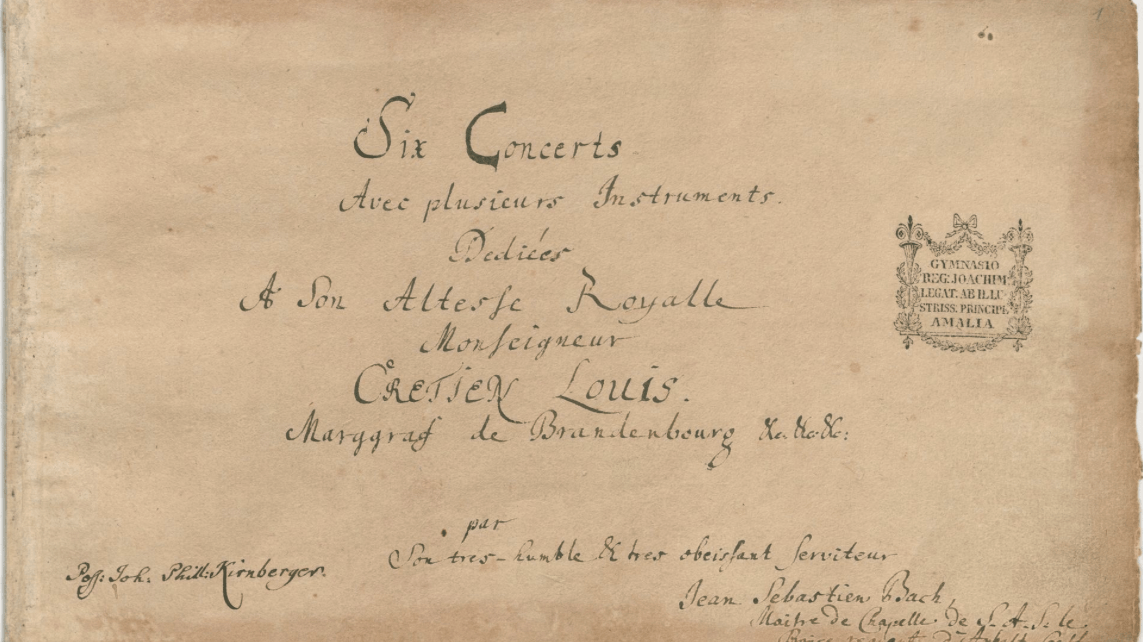

Around 1721, Bach was worrying about his job security. The new wife of his patron, Prince Leopold of Anthalt-Cöthen, was not interested in music. The court’s funds were being reallocated. As a result, Bach compiled a collection of “Six Concertos for Several Instruments” from earlier works and sent the bundle to Prince Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg. In 1719, Bach had traveled to Berlin to negotiate the purchase of a harpsichord from the Prince. During that visit, the Prince commissioned Bach to write some orchestral music. Bach offered the following dedication, dated March 24, 1721:

As I had the good fortune a few years ago to be heard by Your Royal Highness, at Your Highness’s commands, and as I noticed then that Your Highness took some pleasure in the little talents which Heaven has given me for Music, and as in taking Leave of Your Royal Highness, Your Highness deigned to honour me with the command to send Your Highness some pieces of my Composition: I have in accordance with Your Highness’s most gracious orders taken the liberty of rendering my most humble duty to Your Royal Highness with the present Concertos, which I have adapted to several instruments; begging Your Highness most humbly not to judge their imperfection with the rigor of that discriminating and sensitive taste, which everyone knows Him to have for musical works, but rather to take into benign Consideration the profound respect and the most humble obedience which I thus attempt to show Him.

It appears that Bach received no response or money from the Prince. In fact, it’s possible that the manuscript was never even opened. In contrast to Bach’s orchestra in Cöthen, the Prince’s musicians may not have been good enough to play these virtuosic and complex pieces. In 1723, Bach became Kapellmeister at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig where he remained until his death in 1750. The “Brandenburg” Concertos remained unknown and unperformed until they were published in 1850.

The “Brandenburg” Concertos elevate the concerto grosso (“big concerto”) form to its most sublime heights. Originating in Italy with composers such as Corelli and Vivaldi, the concerto grosso employs a back-and-forth dialogue between the full ensemble and small groups of solo instruments. In each of the six “Brandenburg” Concertos, a different combination of solo instruments take the stage. Each Concerto has its unique persona and atmosphere. It is the unique combination of instruments and the magical way in which they converse that gives this music its profound drama.

Over the next few months, we’ll explore each of Bach’s “Brandenburg” Concertos. For today, we’ll begin with Concerto No. 1 in F Major, scored for thirteen musicians: three oboes, bassoon, two horns, violino piccolo (a small violin tuned a third higher than usual), a quintet of strings, and harpsichord continuo. This is the largest and most “symphonic” of the six. It’s also the only one set in four movements. With the addition of the horns, this music is filled with allusions to the hunt. The Concerto is an extensive reworking of Bach’s Sinfonia in F Major, BWV 1046a, music that may have formed the introduction to “Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd,” BWV 208, a secular cantata written in 1713 for hunting festivities celebrating the birthday of Duke Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels.

The first movement comes to life with an exuberant dialogue of voices. Notice the giddy three-against-two cross rhythms in the horns:

The second movement, Adagio, takes us to a completely different world, set in a mournful, lamenting D minor. As the theme moves from one voice to another (including the lowest instruments), there is no sense of “melody” or “accompaniment.” Each voice is equally important in this sublime drama without words:

Listen to the way buoyant, dance-like Allegro third movement plays tricks with our sense of the rhythmic pulse. At key moments, a predictive feeling of three beats (within a larger “one”) gets thrown off, yet the music “rights” itself just in time:

The first “Brandenburg” Concerto concludes with a French-styled minuet and a Polish polacca, set over a drone. In the second Trio, we return to the celebration of the hunt with the horns:

Five Great Recordings

- Trevor Pinnock and the European Brandenburg Ensemble Amazon (This 2007 recording is featured, above).

- Rinaldo Alessandrini and Concerto Italiano (2014)

- Akademie fur Alte Musik Berlin

- Gottfried von der Goltz and the Freiburger Barockorchester

- Reinhard Göbel and Musica Antiqua Köln

I think the Brandenberg Concerto no1 sounds like Handel not Bach. I wonder if you agree?