Perhaps, as Alex Ross suggests in the opening pages of his bestselling book, The Rest is Noise, twentieth century music was born with the first scandalous performances of Richard Strauss’ 1905 opera, Salome.

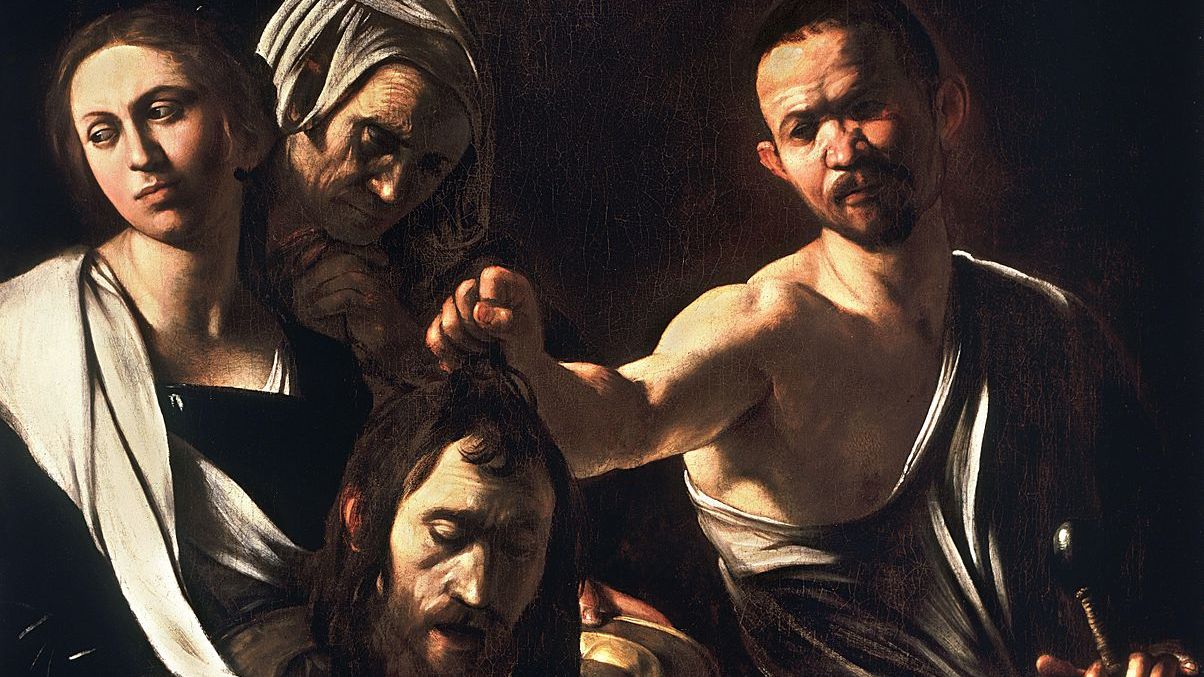

Set in one act, the opera was inspired by Oscar Wilde’s French play based on characters from the Gospel of Saint Matthew. The imprisoned Jochanaan (John the Baptist) becomes an object of desire for princess Salome, the teenage stepdaughter of King Herod of Judaea. Jochanaan rejects her depraved advances. Later, over the objections of Herodias, the lustful, incestuous Herod begs Salome to dance for him. As a reward, he promises to grant her whatever her heart desires. She complies with the Dance of the Seven Veils, an exotic striptease which renders her naked at his feet. Following the dance, Salome demands Jochanaan’s head on a silver platter. Herod attempts to dissuade her with promises of riches, but it is to no avail. “Hide the moon, hide the stars! Something terrible is going to happen!” exclaims the horrified Herod before the deranged Salome kisses the severed head. A moment later, he orders his soldiers to “Kill that woman!”

At the time of its premiere, Salome was widely banned by censors. Consent for a performance at the Vienna State Opera, to be conducted by Gustav Mahler, was not granted. Following a crusade led by the daughter of J.P. Morgan, a 1907 staging at the New York’s Metropolitan Opera was cancelled after one performance. A physician wrote to the Times to denounce Salome as a “detailed and explicit exposition of the most horrible, disgusting, revolting, and unmentionable features of degeneracy…that I have ever heard of, read of, or imagined.” Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II, otherwise a fan of Strauss’ music, warned that it would do the composer “a lot of damage.” Yet, Strauss later quipped, “Thanks to that damage I was able to build my villa in Garmisch!” Following the successful premiere in Dresden, Salome received a subsequent staging in Graz, with Mahler, Giacomo Puccini, and Arnold Schoenberg in attendance.

With Strauss’ Salome, tonality begins to fray. Wagnerian chromaticism is pushed to its breaking point. In its place, fragmented, post-tonal strands emerge which anticipate the music of Schoenberg. At first, the final moments of Salome seem to be building towards a transfiguring climactic resolution akin to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Yet, the demented necrophilia of Salome is the antithesis of enduring love, and the moment turns into a nightmare. A cadence in C-sharp major is marred by a sudden flash of polytonality. A low A dominant seventh is smashed against a higher F-sharp major chord. It’s a sonority which has been called, “the most sickening chord in all opera,” an “epoch-making dissonance with which Strauss takes Salome…to the depth of degradation,” and “the quintessence of Decadence: here is ecstasy falling in upon itself, crumbling into the abyss.” (Craig Ayrey) With the anticipated transfiguration abruptly interrupted, the final bars of Salome suggest a visceral harmonic decapitation.

Recordings

- Strauss: Salome, Op. 54, Herbert von Karajan, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Agnes Baltsa, Hildegard Behrens, José van Dam, Karl-Walter Böhm Amazon

- a Royal Opera House Covent Garden performance conducted by Christoph von Dohnányi featuring Catherine Malfitano Amazon

Featured Image: “Salome with the Head of John the Baptist” (c. 1607/1610), Caravaggio

O.M.G. – fearsome performance of a devastating story! Thank you so much for putting this gruesome yet essential opera into cultural and historical context. I particularly enjoyed your final paragraph describing how it pushed music into the 20th century, not unlike “The Rite of Spring.” It’s been a while since I read Alex Ross’s portrayal in “The Rest is Noise” so your refresher here compels me to return and spend some more time with this amazing work.