The music of Dmitri Shostakovich falls into two categories. There are the faceless proletarian marches, patriotic hymns, propagandistic film scores, and other superficial works which were written to appease Stalin and his cultural censors. Then, there is the music that Shostakovich dared not release publicly until after Stalin’s death in 1953. Much of this music ended up hidden in the composer’s “desk drawer.”

The Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor was a piece destined for the desk drawer. The work’s completion in 1948 coincided with the “anti formalism” campaign of the Zhdanov Doctrine in relation to music. Under the directive, all art had to serve a larger social purpose. In anticipation of an eventual performance, Shostakovich worked in collaboration with the Concerto’s dedicatee, the violinist David Oistrakh, on revisions to the score. The October 29, 1955 premiere, featuring Oistrakh with the Leningrad Philharmonic, conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky, was an “extraordinary success.”

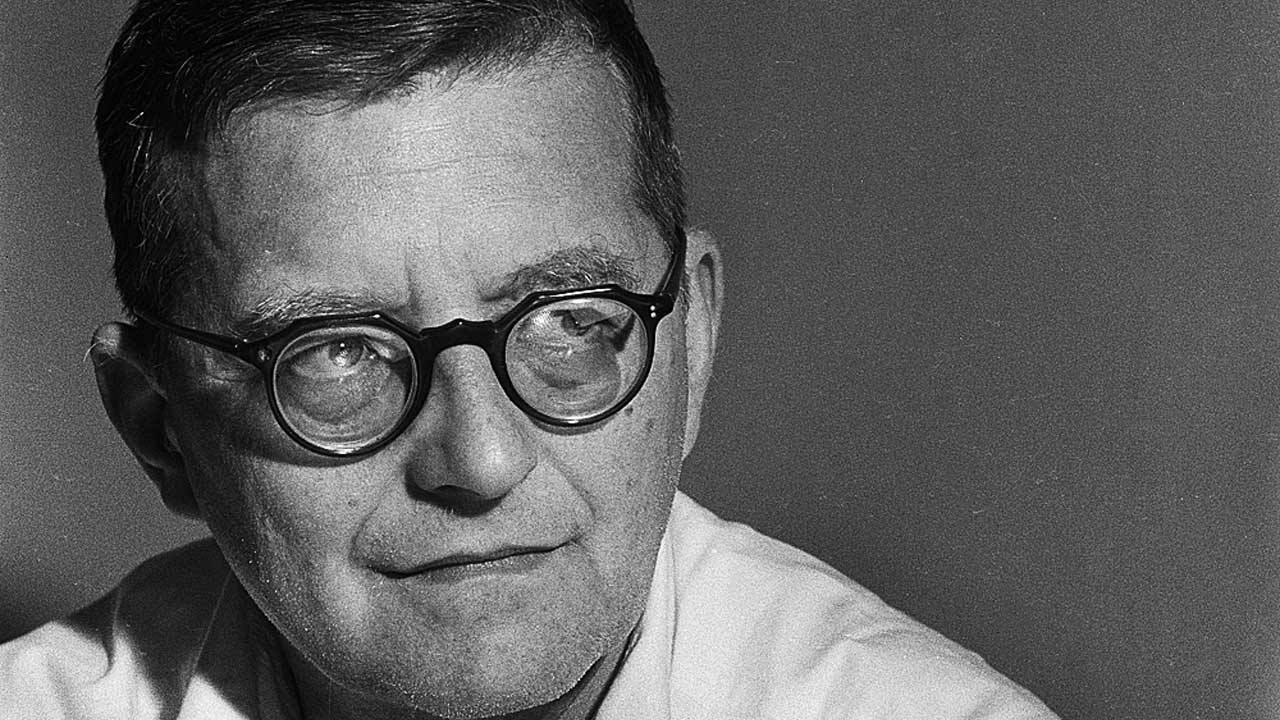

In 1997, Richard Taruskin wrote, “No one alive today can imagine the sort of extreme mortal duress to which artists in the Soviet Union were subjected, and Shostakovich more than any other.” For Shostakovich, a knock on the door from the KGB (secret police) in the middle of the night was a real possibility. For a time, the composer slept in the stairway of his apartment building to spare his wife and children the trauma of seeing him taken away. It was amid this terrifying environment that Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto was born.

Set in four movements, the Concerto was once described by Shostakovich as “a symphony for solo violin and orchestra.” Its unusual instrumentation includes a full wind section, four horns, tuba, tambourine, tam-tam, xylophone, celesta, and two harps, but no trumpets or trombones. The first movement is titled, Nocturne: Moderato. This is not the magical, shimmering night music of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Instead, we are plunged into the quiet terror of the night. This ghostly nocturnal landscape is filled with lament and persistent anxiety. For Oistrakh, it represented “a suppression of feelings.”

The second movement is a demonic Scherzo. It is a grotesque dance, infused with jagged rhythms. The snarling solo violin (often called the Devil’s instrument) is surrounded by ghoulish, shrieking woodwinds. Echoes of klezmer music seem to rise in defiance of Stalin’s anti-Semitic reign of terror. Shostakovich’s signature is imprinted on the music in the form of the famous DSCH motif, in which the pitches D, E-flat, C, B translate into the composer’s initials using the German alphabet.

The third movement is a Passacaglia. Popular during the Baroque period, this form features a series of variations over a recurring bass line in triple meter. Shostakovich’s seventeen measure long passacaglia theme takes the form of a funeral dirge. Following its initial announcement by the horns and low strings, it is heard as a somber woodwind chorale. Gradually, new voices enter, one by one, to join the solo violin in a soulful, lamenting musical conversation. With every repetition of the passacaglia theme, the conversation becomes increasingly frustrated in the face of inexpressible sadness. In an extraordinary, climactic moment, the bass line emerges as anguished, defiant octaves in the solo violin. Eventually, the elegiac procession fades away. We are left with the solitary voice of the solo violin, and an extended cadenza which grows in intensity, brings a ferocious restatement of the DSCH motif, and delivers us into the final movement.

“Please consider letting the orchestra take over the first eight bars in the Finale so as to give me a break; then at least I can wipe the sweat off my brow,” David Oistrakh pleaded, noting the extent to which the Concerto is a test of physical and emotional endurance. The final movement (Burlesque: Allegro con brio – Presto) is a boisterous, sardonic romp. It is wild, unabashed Russian fiddle music. Oistrakh described it as “a joyous folk party, [with] even the bagpipes of traveling musicians.” There is a mocking remembrance of the Passacaglia theme. It is a fragment of this theme, heard in the horns, which has the final word as the Burlesque hurtles to a conclusion.

Five Great Recordings:

- Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 99, Maxim Vengerov, Mstislav Rostropovich, London Symphony Orchestra Amazon

- David Oistrakh with Maxim Shostakovich and the London Philharmonic Orchestra (1972 studio recording)

- Hilary Hahn with Marek Janowski and the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra

- Leonid Kogan with Evgeny Svetlanov and the USSR State Symphony Orchestra (1960 live recording)

- Viktoria Mullova with Andre Previn and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The best modern recording is by Frank Peter Zimmermann. He recorded both concertos some years ago, and he does a good job. I would put him right behind Kogan and Oistrakh.

As good as any violin concerto ever written – the Shostakovich 1st is a dark yet beauteous gem of a piece. The Vengerov-Rostropovich version cries and sizzles!

I agree with your selections, but the ultimate performance is Oistrakh with the NY Phil conducted by Mitropoulos. The later stereo recording with the composer’s son is excellent but the earlier recording is both more moving and more intense…

Surely, Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto also has the distinction of being the last major work—perhaps the final work of any kind—to become part of the standard repertoire.

I think his Cello concerto came after and that is played very regularly. Made even more popular by Sheiku Kanneh Mason when he won the BBC competition with it.

Heard it played in Haifa last week with Haifa Symphony Orchestra lead cellist playing the solo – amazing performance especially with rockets firing in from Lebanon – not that far away!

Amazing concert with charged playing from ther elatively young orchestra.

Shaber, thank you for the correction. Stay Safe!

lords you can write Mr Judd.

Prof Taruskin would be proud.

may your light shine through endless staves and students

and yes desks

Thank you, Leo!

Thanks for another excellent summary. You are my go-to site for reading about pieces as I listen to them. Another great recording not on the list (in my opinion, better than some on the list) – Itzhak Perlman with the Israel Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta conducting.