As a musical form, the serenade implies light, entertaining music of the evening, set in a loose collection of movements which resembles a divertimento.

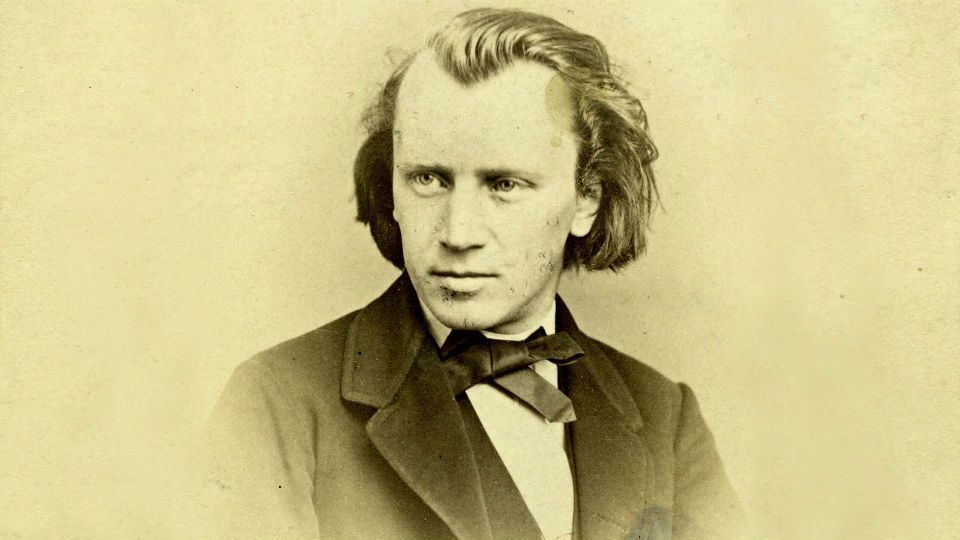

The two youthful Serenades which Johannes Brahms wrote in his early twenties conform to this description. Yet they can also be heard as trial runs on the path to a symphony. It was Robert Schumann who heard “veiled symphonies” in Brahms’ early piano music, and who anticipated that “we may expect all kinds of wonders” from a genius who would become the heir to Beethoven. Sensing that he was treading in the footsteps of a giant, Brahms wrote that Schumann’s praise “induces me to use extreme caution selecting pieces for publication.” Additionally, he recognized that “After Haydn, writing a symphony was no longer a joke but a matter of life and death.”

The two Serenades (Op. 11 and Op. 16) allowed Brahms to experiment freely with form two decades before the completion of the First Symphony. The First Serenade was conceived as a nonet, although initially Brahms gave it the bold title, “Symphony-Serenade,” before reconsidering. In the Second Serenade, completed in the autumn of 1859 and dedicated to Clara Schumann, Brahms’ distinct voice comes more into focus. Originally written for full orchestra, it was later rescored for chamber orchestra. Omitting violins, the final version was scored for low strings, woodwinds, and horns. The result is music with a sunny, pastoral flavor. We hear something similar in the opening movement of the German Requiem, which omits the violins, and in the first moments of the Second Symphony, where the violins eventually enter covertly.

The Serenade No. 2 in A Major, Op. 16 begins with warm, gently flowing lines, initiated by the woodwinds, which wander happily away from the home key of A. The first movement (Allegro moderato) unfolds in Sonata form. The end of the exposition leads into a false “repeat” which is soon swept away by an extended development section. The final notes drift away with a charming suddenness.

The second movement (Scherzo. Vivace) is filled with the exuberant, fun-loving spirit of a folk dance. With vibrant cross rhythms, we can imagine the boisterous, out-of-step hilarity of a dance hall in a remote corner of the Austrian or Czech countryside.

With the third movement (Adagio non troppo), the Serenade takes a somber and dramatic turn. The shivering opening lines mirror the stepping motion of the first movement’s main theme. Soon, we realize that the movement is a passacaglia, a form which was popular during the Baroque period in which variations develop over a repeating bass line. At moments, the music seems to pay homage to J.S. Bach. Later in the movement, the violas restate the passacaglia line, over which a fugal counterpoint emerges. Regarding this mysterious and transcendent music, Clara Schumann wrote in a letter to Brahms,

What shall I say about the adagio…I cannot find the words to express the joy it has given me and yet you want me to write at length! It is difficult for me to analyze what I feel; it impels me to something which gives me pleasure, as though I were to gaze at each filament of a wondrous flower! It is most beautiful!…The whole movement has a spiritual atmosphere; It might almost be a (Kyrie) Eleison. Dear Johannes, you must know that I can feel it better than express it in words.

Set in 6/4 time, the fourth movement bears the strange title, Quasi menuetto. This expansive music is far removed from the humor of a Haydn minuet. Instead, it is filled with irregular phrases and echoes of Schubert. Moving from D to F-sharp minor, the trio explores strange and ghostly territory.

The final movement (Rondo. Allegro) is jubilant, carefree, and adventurous. At moments, this cast of instrumental voices comes together in a glistening toy soldier march. For the first time, we hear the bright, cheerful tones of the piccolo. An exercise on the road to monumental symphonic form, the A major Serenade ends as pure fun.

Five Great Recordings

- Brahms: Serenade No. 2 in A Major, Op. 16, Riccardo Chailly, Gewandhausorchester Amazon

- Sir Charles Mackerras and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra

- Istevan Kertesz and the London Symphony Orchestra

- Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic

- Kent Nagano and the Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra

Thank you for your wonderful posts!