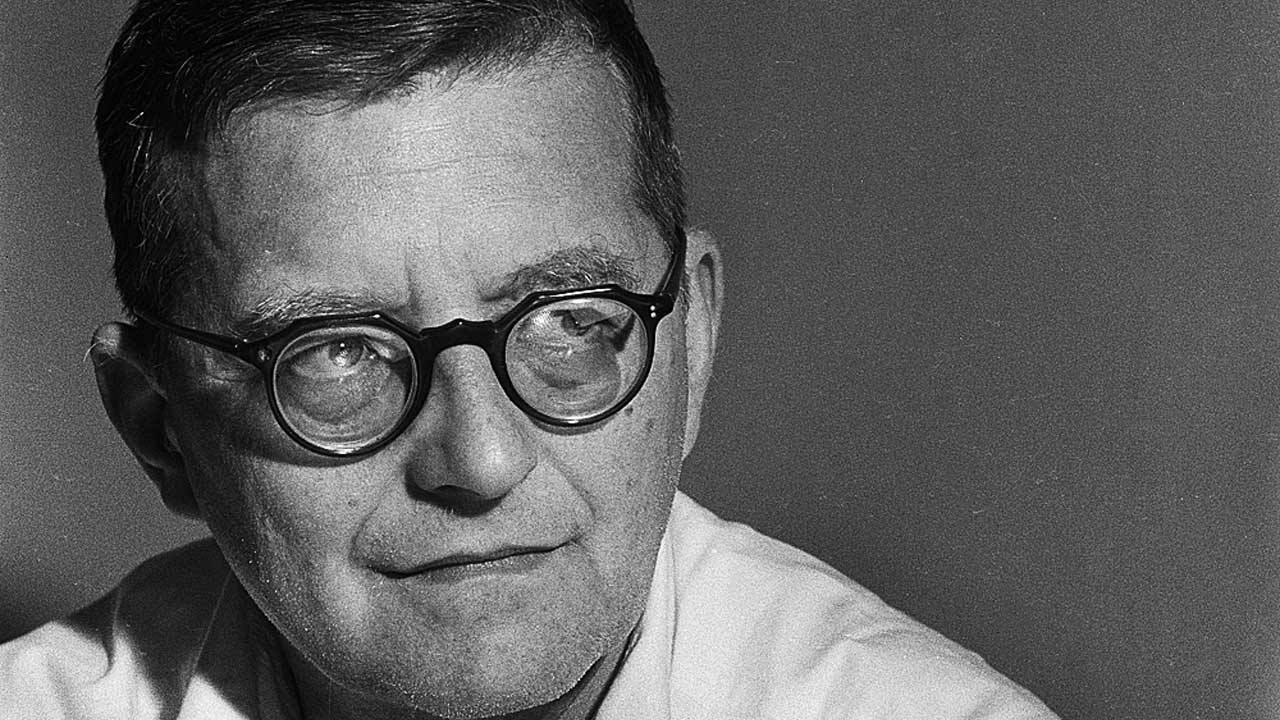

In his later years, the cellist, Mstislav Rostropovich, recalled a conversation that he had with Nina Vasilyevna, the wife of Dmitri Shostakovich. Rostropovich wondered what he could do to encourage Shostakovich to write a concerto for the cello. “Slava,” she answered, “if you want Dmitri Dmitriyevich to write something for you, the only recipe I can give you is this—never ask him or talk to him about it.”

Eventually, in July of 1959, Shostakovich did compose his First Cello Concerto, which he dedicated to Rostropovich. The famous cellist, who went on to give both the Russian and American premieres of the work, memorized the entire piece in four days. Rostropovich, a lifelong friend and chamber music partner of Shostakovich, had been one of the composer’s students at the Moscow Conservatory in 1943. Soon after, Shostakovich lost the teaching position amid an “anti-formalist” witch hunt by the Soviet cultural authorities. Partially inspired by Prokofiev’s Sinfonia Concertante, Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major, Op. 107 reflects, with sardonic defiance, a gloomy climate of terror and oppression that, only in the late 1950s, had begun to thaw.

In a preface to the score, Shostakovich wrote, “This four-movement concerto is divided into two large parts: the opening movement, and then three more movements played without pause. Together, they form an integral whole with unified themes and images.” The Concerto’s principal recurring theme is the four note motif which opens the first movement (Allegretto), where it is met with ghoulish woodwind retorts. The four notes are derived from the DSCH motif, a series of pitches which correspond to the composer’s initials using the German alphabet, and which return throughout his works. Here, as in Shostakovich’s turbulent Eighth String Quartet (1960), the motif repeats with obsessive persistence. It is a bold musical inscription which unrelentingly seems to assert the sanctity of the individual.

Shostakovich described this ferocious opening movement as a “jocular march.” Its ties to the composer’s score for the 1948 film, The Young Guard, which depicted Soviet soldiers being marched to their deaths by the Nazis, make the music seem all the more grotesque and sarcastic. Behind the terror lies the most ridiculous of military marches.

The First Cello Concerto is scored for a chamber orchestra. No brass instruments are used, apart from a single horn which becomes a predominant recurring voice. Raucously and almost mindlessly, it blasts out the principal motto. In the second movement (Moderato), the horn becomes a voice of distant lament. Here, the cello’s haunting melody rises over a gloomy ostinato. It grows into a passionate statement of anguish and despair which climaxes with a single timpani strike. In the final, chilling moments, the solo cello line dissolves into ghostly artificial harmonics and enters into a duet with the celesta.

Drifting into solitude, the third movement is a cadenza in which the solo cello reflects on the motifs of the previous movements. It is an intimate soliloquy which becomes increasingly agitated and leads directly into the final movement (Allegro con moto).

The Concerto concludes with a wild rondo, punctuated by shrieking woodwinds and timpani strikes. At moments, it takes the form of hideous circus music. Hidden within the music is a deformed version of Suliko, a Georgian folksong which was a favorite of Joseph Stalin. Shostakovich quoted the same song in his cantata, Rayok, a vicious satire of the Soviet system. In the final moments, the motif from the opening of the first movement returns and repeats, jeeringly. The final cadence arrives with timpani raps and the mocking blast of the horn.

I. Allegretto:

II. Moderato:

III. Cadenza:

IV. Allegro con moto:

Five Great Recordings

- Shostakovich: Cello Concerto No. 1 in E Flat Major, Op. 107, Mischa Maisky, Michael Tilson Thomas, London Symphony Orchestra Amazon

- Mstislav Rostropovich with Gennady Rozhdestvensky and the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra (live 1960 recording)

- Mstislav Rostropovich with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra

- Steven Isserlis with Avner Biron and the Israel Camerata Jerusalem

- Johannes Moser with Stanisław Skrowaczewski and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra