As a musical form, the “theme and variations” is pure fun. For the composer and performer, it can represent the ultimate display of cleverness—as if to say, “listen to what I can do!” We can imagine Mozart, Beethoven, or Schubert showing off at a party with a series of increasingly intricate keyboard variations on a given theme.

Sergei Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43 is filled with this kind of adventure and frolicking exuberance. It delivers blazing virtuosity with a twinkle in the eye. Rachmaninov composed twenty four variations based on the 24th and last of Niccolò Paganini’s Caprices for solo violin, composed in 1817. The jaunty and mysterious A minor theme has provided fertile ground for numerous composers, from Schumann, Liszt, and Brahms, to Andrew Lloyd Webber and Fazıl Say.

Rachmaninov composed the Rhapsody in six weeks during the summer of 1934 while staying at his vacation home in Switzerland. A day after completing the work, in a letter dated August 19, he wrote, “I’ve kept myself at work, working literally from morn to night, as they say.” The premiere took place at the Lyric Opera House in Baltimore on November 7, 1934, with Rachmaninov at the piano and Leopold Stokowski leading the Philadelphia Orchestra. Hours before going onstage, Rachmaninov reportedly suffered performance anxiety and steadied his nerves with a glass of crème de menthe, concealed under the piano.

While the variations unfold as a continuous stream, the outline of a three movement concerto (fast-slow-fast) is perceptible. The introduction begins with a gruff statement of the theme’s distinctive four-note turn. Plunging into the adventure, it suggests both ferocity and humor. Following Beethoven’s example in the finale of the Third Symphony, we are presented first, not with the theme, but with a variation. In fact, it is the theme in spare, skeleton form. Soon, the violins present the full melody, punctuated by key notes played by the solo piano, and we are off. It is a dazzling musical conversation filled with virtuosity for soloist and orchestra alike.

Paganini’s theme is, itself, a subtly inverted variation on the Dies irae, the 13th century Gregorian chant of the dead, the “Day of Wrath”. (Appropriately, a myth developed that Paganini’s mother sold his soul to the devil in a Faustian exchange for his violin skills). The Dies irae is a recurring motif throughout Rachmaninov’s works, from the haunting tone poem, Isle of the Dead to the valedictory Symphonic Dances. It is even lurking in the first four notes of the famous Vocalise. In the Rhapsody’s seventh variation, the Dies irae emerges as a solemn chorale in the solo piano, joining Paganini’s theme, which can be heard in the bassoon. The violins interject with the theme’s four-note motivic fragment, played as a ghostly ricochet (dropping the bow from above). The Dies irae returns in the 10th and 24th variations.

The Rhapsody’s second section begins with Variation 11, which moves to an exotic, impressionistic landscape. Rachmaninov joined Vladimir Horowitz in his admiration for the American jazz pianist, Art Tatum. (Both considered Tatum to be the greatest living pianist). In the fifteenth variation (Più vivo scherzando), Rachmaninov pays homage to the brilliance of Tatum’s stride style keyboard passagework. (9:46)

The sixteenth and seventeenth variations move into mysterious, shadowy territory, with shuddering tremolo in the strings. Then, suddenly the clouds part, and we arrive at the famous eighteenth variation. (Andante cantabile) The opening four-note motif of Paganini’s theme shifts from minor to a warm, sensuous D-flat major, and is inverted. Heard first with the quiet intimacy of the solo piano alone, this new melody grows to become a declaration of soaring passion. It is not just the melodic line, but the wrenching notes and harmonies surrounding it, which make this variation so extraordinary.

The playful nineteenth variation (A tempo vivace) quickly sweeps passion aside, and ushers us into the Rhapsody’s final section. In its final moments, the music feels as if it has magically become airborne, climbing to new euphoric heights amid shimmering splashes of orchestral color. The final notes evaporate with the suddenness of a fleeting ghost. In the words of pianist Jon Kimura Parker, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini concludes “with a wink and a question mark.”

This August, 2018 concert performance at Moscow’s Zaryadye Hall features Russian pianist Daniil Trifonov with Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Orchestra:

Paganini: Caprice No. 24 in A minor

The ultimate catchy theme, Paganini’s mischievous melody provides the perfect blueprint for endless variations. Rachmaninov biographer Barrie Martyn observes that “it enshrines that most basic of musical ideas, the perfect cadence, literally in its first half and in a harmonic progression in the second, which itself expresses a musical aphorism; and the melodic line is made distinctive by a repetition of a simple but immediately memorable four-note semi-quaver [sixteenth-note] figure.”

Here is Paganini’s Caprice No. 24, performed in concert by Augustin Hadelich:

Five Great Recordings

- Rachmaninov: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43, Daniil Trifonov, Yannick Nezet-Seguin, The Philadelphia Orchestra Amazon

- Arthur Rubinstein with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Stephen Hough with Andrew Litton and the Dallas Symphony Orchestra

- Zoltán Kocsis with Edo de Waart and the San Francisco Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninov with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra (historic recording)

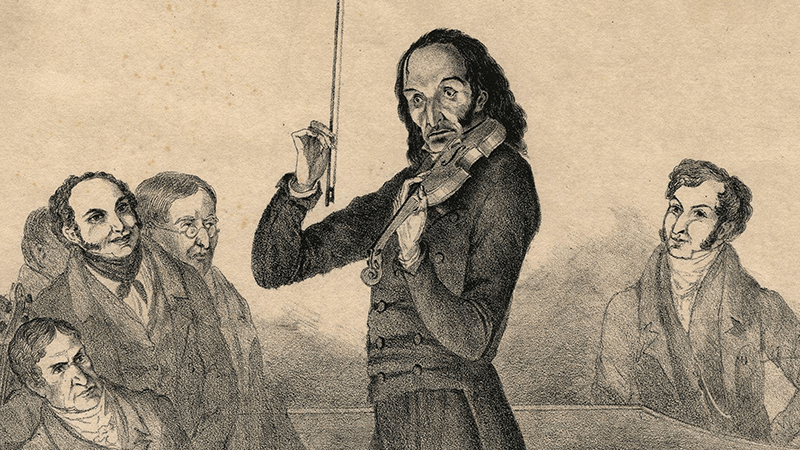

Featured Recording: “The Modern Orpheus,” an 1831 poster advertising a Paganini performance