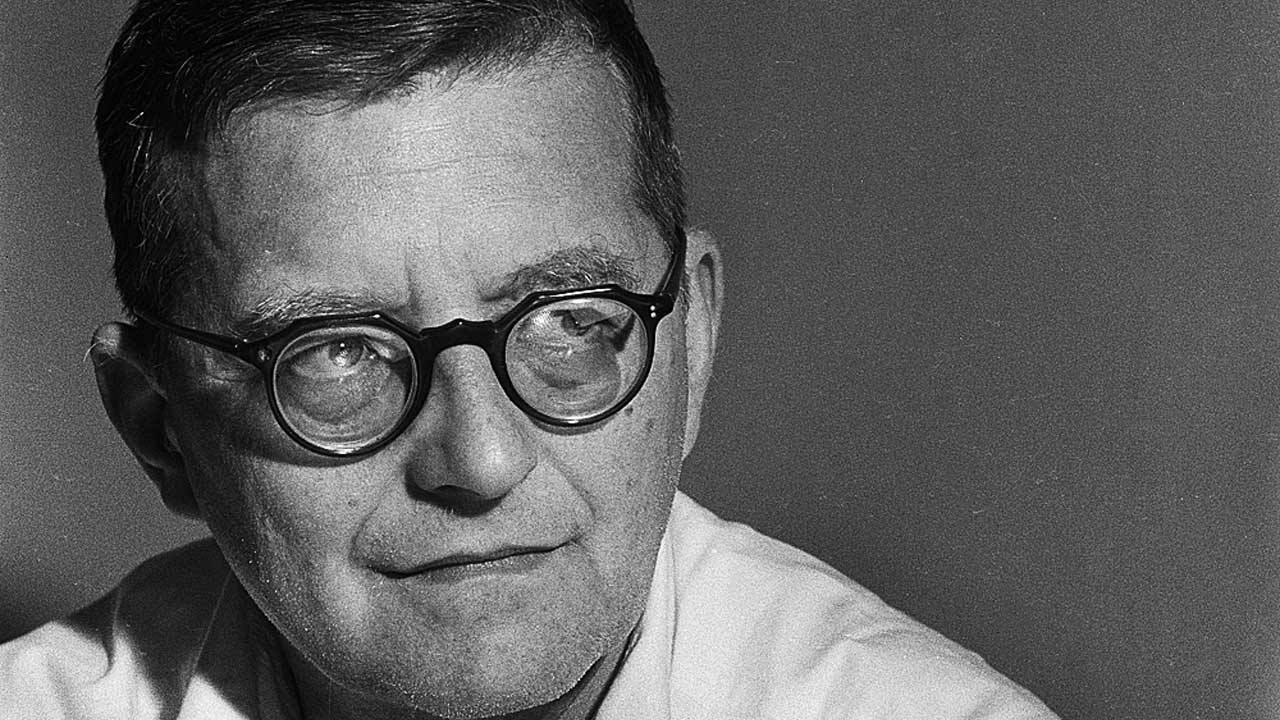

“Very slowly, with difficulty, squeezing it out note by note, I am writing a Violin Concerto,” Dmitri Shostakovich confided to a friend in the spring of 1967, adding, “Otherwise everything is going splendidly.”

The Violin Concerto No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 129 is a shadowy, introverted work. It is mournful and endlessly singing. “Gone are the instantly memorable images, the brightly etched colors and coruscating ferocity,” writes commentator Gerard McBurney. “Instead we find ourselves in a world of half-lights, confessions and deceptions.” Most violin concertos are set in brilliant open-string keys such as G, D, A, or E. Shostakovich’s choice of the veiled, distant key of C-sharp minor inhabits a different harmonic world.

Shostakovich’s final concerto, it is music from the composer’s twilight years, written amid declining health. (The First Violin Concerto was completed nearly 20 years earlier). It was intended to serve as a 60th birthday gift for violinist David Oistrakh, to whom the work was dedicated. In fact, Shostakovich miscalculated Oistrakh’s age by a year. (He was born in Odessa in September of 1908). Regardless, Shostakovich wrote the Concerto with Oistrakh’s soulful, noble sound in mind.

The first movement (Moderato) begins with a single ominous melodic line in the low strings. It emerges as a series of faltering fragments which coalesce and develop. The solo violin enters with a lamenting four-note theme. Entering in succession, the clarinet and higher strings weave new contrapuntal threads. Throughout the Concerto, the solo horn becomes a prominent voice. Soon, we hear the sardonic sounds of a Klezmer street fiddler. There are fragments of a Jewish street vendor’s song from Odessa, Kupite bublichki! (“Come buy my bagels!”) Each of the Concerto’s three movements includes a cadenza for the solo violin. In the first movement, the cadenza takes the form of weaving contrapuntal lines. The movement fades away with the beat of a tom-tom drum.

Set in G minor, the second movement (Adagio) again begins in the gloomy depths of the orchestra. Soon, the darkness is punctured by the radiance of the solo flute’s countermelody. This music pays homage to the counterpoint of Bach, and the austere accompanying lines of the Baroque period. With harsh chords, the solo violin enters into a duet with the timpani. The distant echo of a horn call leads directly into the final movement’s slow introduction.

The final movement (Adagio – Allegro) is a furious rondo. It is a peasant dance filled with gruff humor and biting sarcasm. This wild, exuberant fiddle music is accompanied by crude retorts by the horn and woodwinds. The final cadence is punctuated by tom-tom and timpani raps.

I. Moderato:

II. Adagio:

III. Adagio – Allegro:

Five Great Recordings

- Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 129, Alina Ibragimova, Vladimir Jurowski, State Academic Symphony Orchestra “Evgeny Svetlanov” Hyperion

- David Oistrakh with Kirill Kondrashin and the Moscow Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra

- Maxim Vengerov with Mstislav Rostropovich and the London Symphony Orchestra

- Alena Baeva with Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra

- Lydia Mordkovitch with Neeme Järvi and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Great collection of recordings of Shostakovich violin concertos. I had a student who chose to learn a Shostakovich Concerto and it wasn’t anything I had studied. I told myself I’d have to learn it first before I could really teach this work.