I have written a tiny little piano concerto with a tiny little wisp of a scherzo.

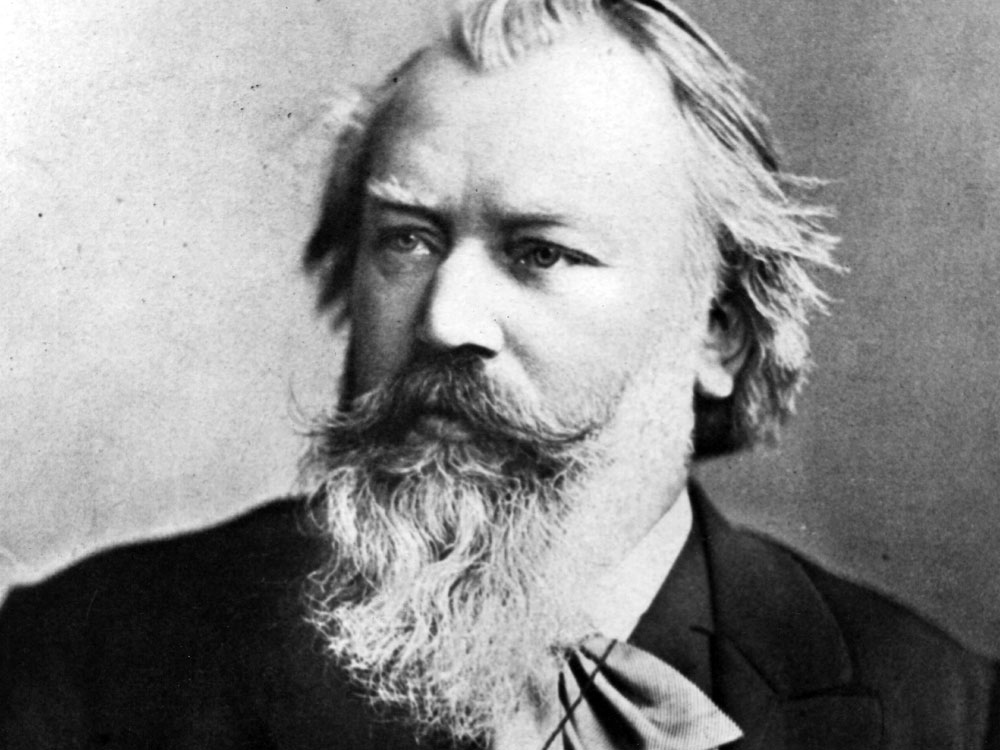

This is what Johannes Brahms wrote, jokingly, following the completion of his Second Piano Concerto in B-flat Major. In reality, he had composed one of the most monumental piano concertos ever imagined- a concerto set in four movements rather than the customary three, which unfolds as a virtual symphony for piano and orchestra instead of the usual “soloist versus orchestra” dichotomy.

The Second Concerto came twenty-two years after the First, a piece which Brahms originally conceived as a symphony. Without warning, the opening of the First Concerto thrusts us into the titanic struggle of a ferociously intense D minor. But the Second Concerto inhabits a much different world. It emerges out of silence with a plaintive, distant horn call. This is the music of nature and the serene pasture- something akin to what we hear in the Second Symphony. Trumpets and tympani are heard only in the first two movements, giving the work an overarching feeling of dramatic decrescendo.

For me, one of the most extraordinary moments in the first movement (Allegro non troppo) occurs at the end of the development section. The music seems to be searching to find a way forward amid hushed mystery and foreboding. Then, suddenly, we hear the familiar, comforting horn call from the opening and realize that we’ve slipped into the recap, almost without knowing it. It’s like returning home and seeing an old friend after a long, difficult trip. (You’ll hear this horn call at other key moments in the movement). And listen to the similarly amazing way we enter the second theme, earlier in the exposition.

I love Brahms’ long, passionately-flowing phrases which often throw in asymmetrical rhythmic surprises. One example of subtle rhythmic surprise (which fundamentally changes the way the music feels) comes early in the first movement when the violins enter, defiantly, a beat earlier than the rest of the orchestra. In the final bars of the movement, listen to the way the same motive is tossed, turned, and deconstructed. In this last example, the piano’s exuberant trills merge with the woodwinds. Piano and orchestra become integrated as one.

“Scherzo” translates as “joke.” But Brahms’ fiery D minor second movement is no joke, and the furthest thing from “a tiny little wisp of a scherzo.” Here the rhythmic games continue. (Just try counting along). The nostalgic voice of the solo cello opens the Andante third movement. Brahms later used this theme in the song Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer (“My Slumber Grows Ever More Peaceful”). There are no insignificant notes in the music of Brahms, or any great composer for that matter. The floating B-flat which emerges in the violins (28:16 in the clip below) is one of my favorite examples of a single note which changes everything. In this passage at the end of the movement, listen to the conversation which takes place between the cello and oboe, and then the flute, with its sudden, brightly contrasting voice. A frolicking rondo concludes the Second Concerto, casting aside the seriousness of the preceding movements.

Here is Emanuel Ax in a live performance at the 2011 BBC Proms. Bernard Haitink is conducting the Chamber Orchestra of Europe:

Five Key Recordings

- Hélène Grimaud and the Vienna Philharmonic with Andris Nelsons (a 2013 Deutsche Grammophon release) Listen to an excerpt here. iTunes

- Krystian Zimerman and the Vienna Philharmonic with Leonard Bernstein (1985 Deutsche Grammophon) Listen here. iTunes

- Rudolf Serkin and the Cleveland Orchestra with George Szell (1966 Columbia) Listen to an excerpt here. iTunes

- Arthur Rubinstein and the Boston Symphony Orchestra with Charles Munch (1952 RCA) Listen here. iTunes

- Sviatoslav Richter and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with Erich Leinsdorf (1960 RCA) Listen here. iTunes