Consider that iconic moment in the 1939 film, The Wizard of Oz, when black and white, tornado-swept Kansas dissolves into the technicolor brilliance of Oz. With the help of a magical cinematographic slight of hand, Dorothy steps into a luscious dreamscape in which every tree and flower seems to be coated in an extra-glossy sheen. The film’s colorfully surreal middle section is bookended by the “real world” of black and white, which returns in the final scene and credits.

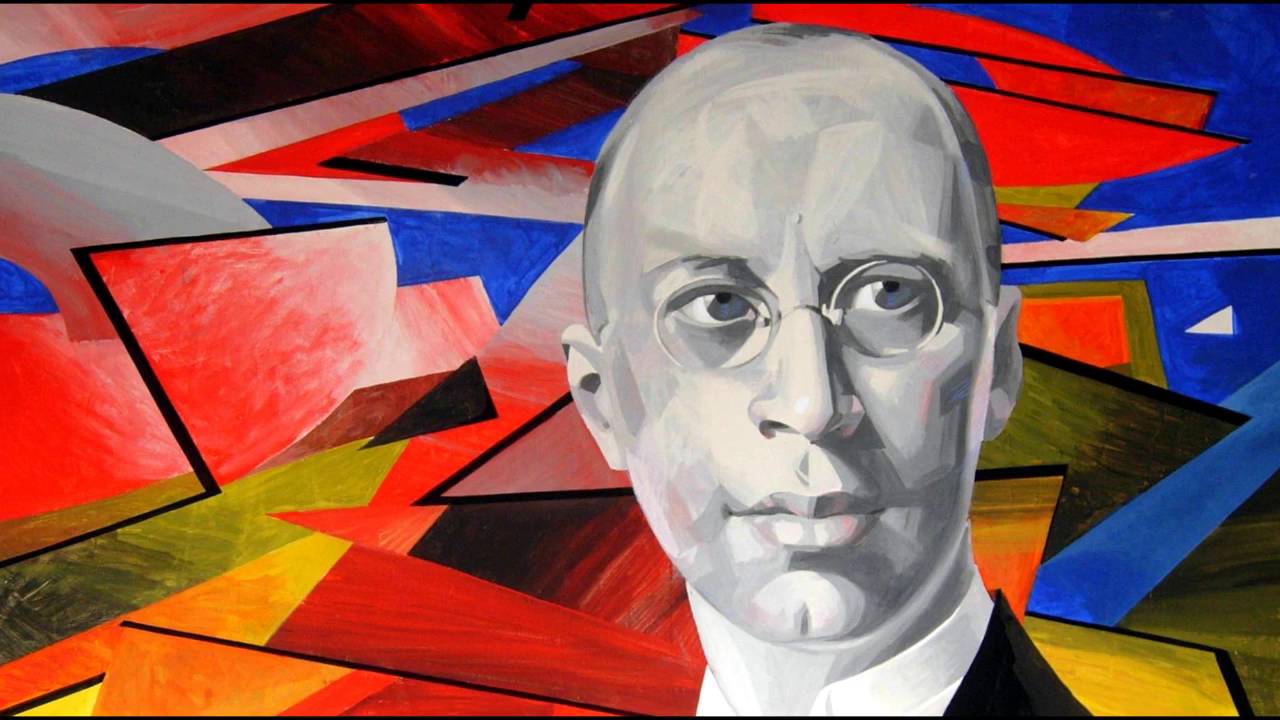

In its most shimmering, dreamlike moments, Sergei Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto, completed in the summer of 1917 amid the turmoil of the Russian Revolution, could be called “music in technicolor.” It begins somewhere up in the clouds with an expansive, gradually-unfolding melody in the solo violin. Woodwind voices awaken slowly and join the conversation. In the score, Prokofiev provides the marking, Sognando (“dreamy”). Soon, we move into a biting, quirky second theme which Prokofiev marks, narrate (“in a declamatory style). “Play it as though you’re trying to convince someone of something” the composer told the young David Oistrakh. As the first movement unfolds, its drama becomes increasingly snarling and agitated. But then, storm clouds subside and we find ourselves back in the floating serenity of the opening theme, this time played by the flute. The final bars seem to evaporate into thin air.

One of the most interesting aspects of this piece is the unusual way the violin interacts with the other instruments. The Russian music critic I. Yampolsky pointed this out when he described the solo violin as “first among equals.” He wrote,

The solo violin is not set against the orchestra, but rises from within to dominate it. This is a unique modern treatment of the violino principale role found in the pre-classic violin concerto.

Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto also disrupts the typical “fast-slow-fast” structure we might expect. The second movement is a grotesque Scherzo- Vivacissimo filled with raspy voices and biting sarcasm. It’s the hellish evil twin of the bubbly, swirling final movement of the “Classical” Symphony which Prokofiev completed the same year.

The final movement (Moderato) opens with more of Prokofiev’s trademark sarcasm: a dry, incessantly rigid rhythmic motor and a cartoonish statement in the bassoon. An interesting dichotomy takes shape as a lushly romantic melody blossoms over this “motor.” The Concerto’s final moments are a tour of glistening technicolor landscapes. Unlike The Wizard of Oz, Prokofiev’s Concerto doesn’t find an ultimate resolution in the rationality of “home.” Instead, it melts into a comforting, yet bizarre, musical hallucination. The first movement’s opening theme returns as a dreamy memory of the original. This passage might even be vertigo-inducing. Who knew that Prokofiev could be so trippy?

Five Great Recordings

- Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Major, Op. 19, Maxim Vengerov, Mstislav Rostropovich, London Symphony Orchestra iTunes– This 1994 recording on the Teldec label is featured above.

- When a youthful David Oistrakh first played this concerto for Prokofiev in Odessa, the composer chastised him for not playing it correctly. Oistrakh and Prokofiev eventually became friends and chess rivals. Oistrakh was regarded as one of the greatest early interpreters of this music. Here is his 1954 studio recording with the London Symphony Orchestra.

- The Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti was drawn to Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto “by its mixture of fairy‑tale naïveté and daring savagery in lay‑out and texture.” Here is his London Philharmonic Orchestra recording with Sir Thomas Beecham.

- Here is an excerpt from James Ehnes’ 2013 recording with the BBC Philharmonic.

- Here is Hilary Hahn’s live concert performance in Madrid with the RTVE Symphony Orchestra.