“What does it mean?”

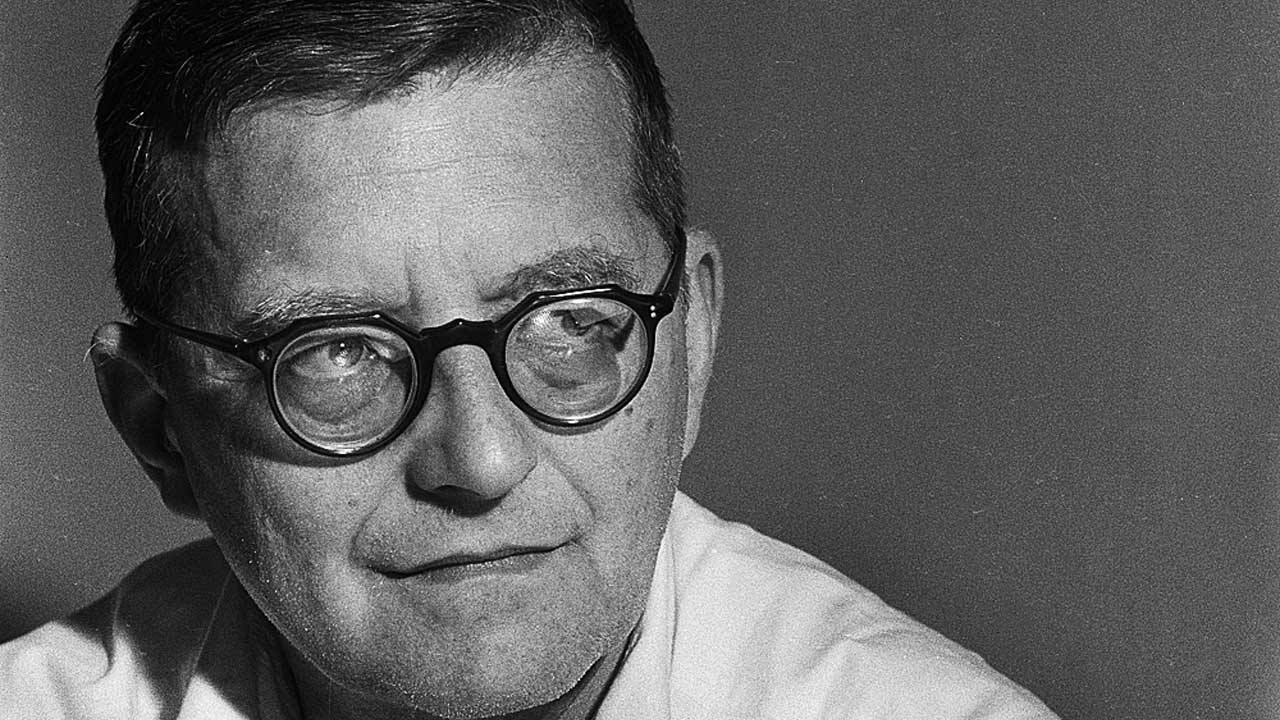

You may find yourself asking this question as you listen to Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 15 in A Major. This final Shostakovich Symphony, written in a little over a month during the summer of 1971 as the composer faced declining health, is filled with persistent and unsettling ambiguity.

First, there are the strange, inexplicable quotes and fleeting allusions to music of earlier composers, as well as cryptic references to Shostakovich’s previous works. It begins only a few minutes into the first movement with a fragment from Rossini’s William Tell Overture, heard in the trumpets. From the first bars, there are echos of the “William Tell” rhythm. But when the quote arrives, it jolts us with its banality. Heard in the wrong instrument (in the original it is played by the strings with ricochet bowing) and the wrong tempo, the motive is stripped of its original meaning. It becomes the kind of sardonic joke that might elicit uncomfortable laughter. A few moments later, the trumpet fanfare openings of William Tell and Mahler’s Fifth merge.

As the Symphony unfolds, references to Mahler, Strauss (Ein Heldenleben), Rachmaninov, and Beethoven’s Egmont Overture emerge. (Could this be an echo of the stepping bass line in the final movement of Brahms’ First Symphony?) In the final movement, we hear the “Fate motive” from Wagner’s Ring Cycle. A fragment from the Prelude of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde melts into a ghostly remembrance of Glinka’s beautiful and melancholy song, “Ne iskushay menya bez nuzhdï” (“Do not tempt me needlessly”), the final lines of which intone the ultimate farewell to life:

Do not augment my anguish mute;

Say not a word of former gladness.

And, kindly friend, o do not trouble

A convalescent’s dreaming rest.

I sleep: how sweet to me oblivion:

Forgotten all my youthful dreams!

Within my soul is naught but turmoil,

And love shall wake no more for thee.

Characters from Shostakovich’s previous works take the stage, from the trombone glissandos of scandal-inducing opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, to the Second Cello Concerto, the Scherzo of the Fourth Symphony, the Fifth Symphony’s triumphant culmination, and a veiled statement of Seventh Symphony’s “Invasion Theme.” These kinds of spontaneous, uncontrollable references can be heard throughout Mahler’s Symphonies. In Shostakovich’s Fifteenth, they seem to reach a fevered climax. It’s the ultimate farewell to the Symphony, and to life, itself.

Even Shostakovich was at a loss when he was asked to explain the significance of all of these quotes. He told his friend, Isaak Glickman,

I don’t myself quite know why the quotations are there, but I could not, could not, not include them.

There are other enigmatic references throughout the Symphony. The five-note motive in the opening of the first movement (E-flat-A-flat-C-B-A) translates in German notation to “SASCHA,” the name of Shostakovich’s nine-year-old grandson. Additionally, the composer seems to have thrown out false clues about the “meaning” of the music. He said that the first movement “describes childhood, a toy-shop with a cloudless sky above.” Yet the music is far from innocent or childlike. The conductor Kurt Sanderling has noted,

In this “shop” there are only soulless dead puppets hanging on their strings which do not come to life until the strings are pulled. (It) is something quite dreadful for me, soullessness composed into music, the emotional emptiness in which people lived under the dictatorship of the time.

Ambiguity is present in the Symphony’s final moments. At the end of the last movement, a shimmeringly colorful chord from Wagner’s “Tristan” (heard earlier) sets the stage for one of the strangest endings in all of symphonic music. Endlessly unfolding motives continue to dance and play while slowly enveloped in a prolonged and sustained open fifth. The sparkling added third of the celesta has the final word.

So what does this music actually mean? Ultimately, this is an unsolvable enigma. To hear what the music truly has to say, we must just listen…

This is a strange symphony, albeit my favourite of Shostakovich’s works, and maybe my favourite symphony ever. I may want to add something- he wrote this partly when he was in the hospital, so to me, I hear some sounds that you may hear in one. The first few notes sound very… clean to me. Especially the celeste throughout the score. Just my two cents.

This is one of my very favorite symphonies as well, along with Stravinsky’s Symphony in 3 Movements and Symphony in C, and Prokofiev’s Symphonies 1, 3, and 6- though Shostakovich’s 15th is probably my favorite among all of them.

Sanderling’s with the Berlin Symphony Orchestra is easily my all-time favorite to date (of the half dozen or so I’ve heard), followed by Pletnev’s interpretation, though I’m about to check out Wigglesworth Kondrashin, and Maxim S’s.

Have just heard Mravinsky’s, which I haven’t seen mentioned on any ‘best of’ lists, but which sounds like a decent interpretation to me with what seems like a certain rawness/lack of polish that actually serves the work in this case. I expect to be returning to it. Obviously everyone hears and may like different things.

But what a musical creation! The morbid and morbid tone, the strong existential quality, the diverse quotations and deconstructive nature- and overall the shift to a profound, if subdued emotionality- I’ve never heard another musical work quite like it. It really does take one out of the everyday state of mind in a dark but IMO necessary manner to understand this life/mortality of ours from another angle.

Just wandered across this post again, and I certainly misspoke on Pletnev being one of my favorite interpretations- I’d meant to say Petrenko’s. I actually don’t like Pletnev’s recording of it at all. Again, though, it’s obviously all personal taste.

Also hadn’t heard Maxim Shostakovich’s premiere recording of the piece with the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra in a while, but recently did- that’s a favorite as well.

BTW, anyone who likes the aesthetic of the Shostakovich’s 15th Symphony but who hasn’t heard his second cello concerto should definitely give it a listen!

Well, leaving aside the fact that the oft-mentioned William Tell quote is actually a misquotation – deliberate or otherwise – and that your supposed reference to Heldenleben is no such thing – just Shostakovich’s characteristic spiky-winds-in-scherzo vein he’d used forever in symphonies and film scores with no discernible Straussian provenance – there’s the problem of “Sascha” as a musical acrostic, because he didn’t have a grandchild called Alexander aged nine or indeed anything else. His male grandchildren were Dmitri Jr. – son of Maxim – and Andrei and Nikolai, his daughter Galina’s sons. None of these reduce in Russian pet-names to Sacha – Andrei becomes Andryusha – and can only refer to an Alex(ander). And no-one seems to know who this was.

I think the MUSICAL quotes mean nothing and sascha was also supposed to lead people down rabbit holes. It was DSCH’S FINAL JOKE. I think it is a rubbish symphony. My teachers teacher’s teacher same from the same class as DSCH.