In music one must think with the heart and feel with the brain.

-George Szell

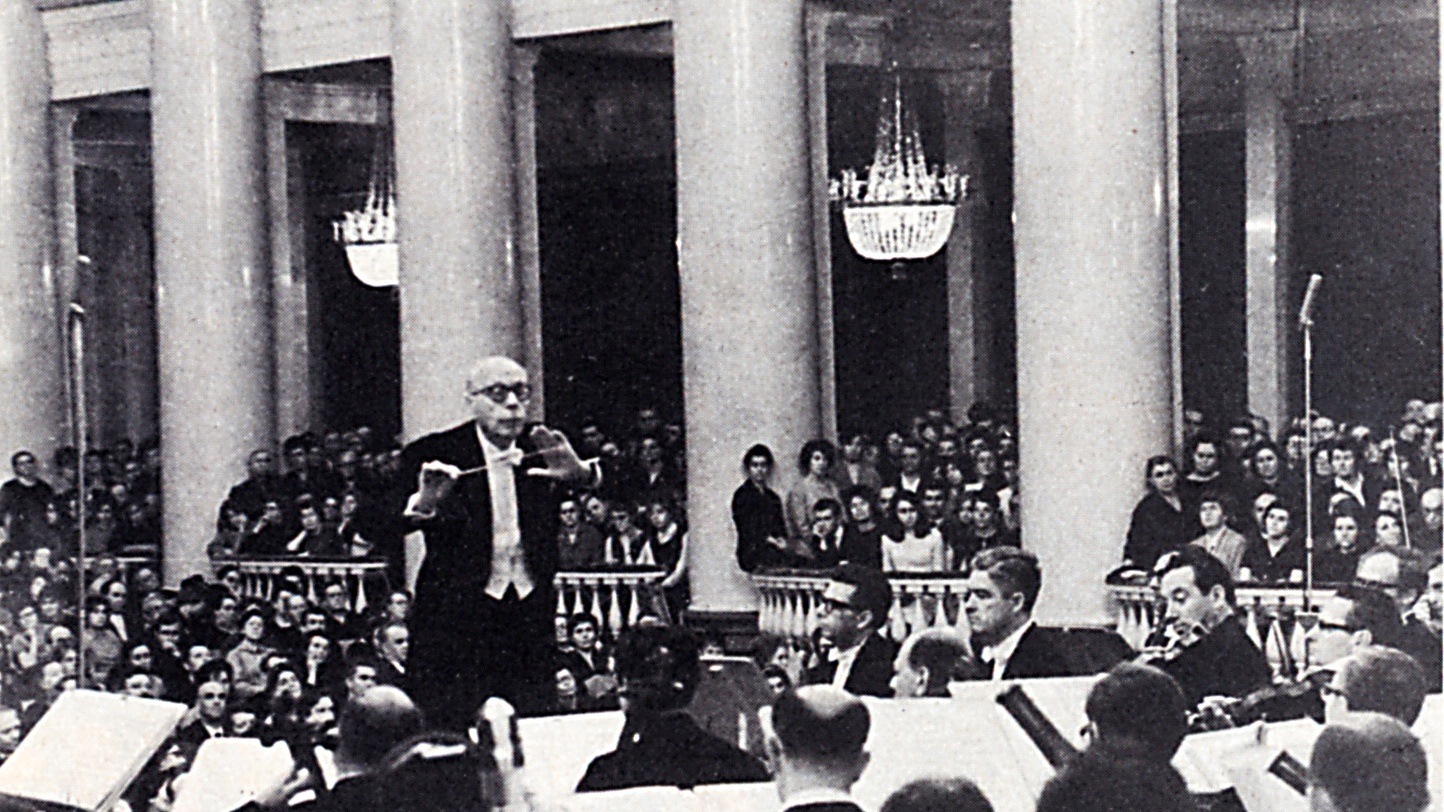

George Szell was music director of the Cleveland Orchestra from 1946 until his death in July, 1970. During that time, the Hungarian-born Jewish-American conductor transformed the orchestra on the industrial shores of Lake Erie into one of the world’s most esteemed ensembles. He created an orchestra with a distinct sound and style- a seamless blend of European warmth, clarity, and refinement, combined with crackling American virtuosity.

Szell ruled over his orchestra as an autocrat, exerting a meticulous attention to detail. Before accepting the job, he demanded total artistic control from the Orchestra’s trustees. On occasion early in his tenure, musicians were fired in the middle of rehearsals, occurrences which would never happen today with the protections of the Union. Under Szell, an orchestra of over one hundred musicians played with the polish and precision of a chamber ensemble. Szell’s autocratic control extended to everything from the custodial staff which cleaned Severance Hall to the personal appearance of members of the orchestra. (Facial hair was forbidden).

In his biography, George Szell: A Life of Music, conductor Michael Charry (who served as Szell’s assistant) remembers the way Szell “sometimes leaned heavily on new players in the Orchestra to toughen them up or bring them up to the Orchestra’s incredibly high standards.” He writes,

Szell possessed a personal intensity that inspired fear and awe. His face could take on a stern expression, and his gaze, magnified by his strong glasses, seemed to penetrate with X-ray power. Even people who had to communicate with him by letter developed cases of nerves. And one could tell when he was in residence from the way Severance Hall was swept and polished. Hard to explain, but it was tangible. And for soloists who worked with him or members of the Orchestra and conducting staff, there was constant tension.

In his autobiography, Violin Dreams, violinist Arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri String Quartet, details his years as assistant concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, where he sat next to concertmaster Josef Gingold. Szell offered the young Steinhardt fatherly guidance, setting up lessons for him with the great violinist Joseph Szigeti. He outlines Szell’s supervision of his purchase of a new violin (which Szell personally “auditioned” in Severance Hall). Steinhardt writes,

He was brilliant but obsessive, deeply knowledgeable but rigid, candid to the point of cruelty, a shrewd collector of the very best players but capable of ruthlessly casting off those who did not meet his standards.

Michael Charry shares some interesting insights into Szell’s recordings with the Cleveland Orchestra:

If rehearsals and concerts were serious business, recordings, which were for posterity, were even more a life-and-death matter. Preparation for a concert included detailed preparation of the orchestra parts weeks ahead of the first rehearsal. Preparation for a recording could mean that the parts were ready months and even a season ahead of the recording session. Orchestra members were expected to take the parts out of the library and practice them until they were note-perfect at the first rehearsal, and they did just that. “We begin where others leave off” was not an idle wish for the Cleveland, it was a daily fact of life.

With five rehearsals a week, Szell could properly prepare for a concert with four, and use the fifth to read ahead new works of unusual difficulty or works that were going to be recorded in the future. The recording sessions were planned to take place after the piece had been rehearsed and performed at least once that season, even though it may have been in the Orchestra’s regular repertoire in previous seasons.

Recordings were usually made on Friday mornings, after the Thursday-evening subscription concert. The pressure and artificiality of recording, without the stimulus of a live audience, makes it difficult for artists to produce their best. Naturally, the results could not always achieve the spontaneity of a performance; in order to duplicate the concert situation as much as possible, however, Szell preferred to record in long takes, later supplemented by inserts for editing. On some recordings, movements and even whole works—the Moldau comes immediately to mind—were the results of a single take with no editing. That the players were able under recording conditions to perform at such consistently high levels speaks for their highly disciplined professionalism, pride, and artistry. And some of the recordings are spectacular!

Let’s listen to five of those “spectacular” recordings. Feel free to share your own favorites in the comment thread, below.

Schubert: Symphony No. 9 “The Great”

In this 1957 recording, the Cleveland Orchestra’s warm, noble sound is on display. Every voice speaks with remarkable clarity and precision. At moments, there is an almost frightening intensity to the sound. Also, notice the powerful sense of underlying rhythm which keeps the music unfolding with a feeling of sublime inevitability.

Dvořák: Symphony No. 8

For all of Szell’s “autocratic” control, the music seems to come alive with a remarkable sense of spontaneity. This 1958 recording is still considered to be an “authoritative” performance:

Wagner: Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey, from Götterdämmerung

So much of the drama of Wagner’s operas comes from the orchestra, with all of its intertwining leitmotifs. This excerpt begins with the awakening of Siegfried and Brünnhilde after their first night together. Siegfried places a gold ring on Brünnhilde’s finger. Later, we hear Siegfried’s horn call and the swirling waters of the Rhine River. One of my favorite moments in this piece is the ear-bending chromatic contrary motion of this passage.

Strauss: Death and Transfiguration

In a previous post, we heard the spectacular virtuosity of Richard Strauss’ Don Juan performed by Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. Death and Transfiguration is also included on that 1957 album:

Dutilleux: Métaboles pour orchestre

A number of world premieres were given in Cleveland during Szell’s tenure. The music of Bartók, Hindemith, and Prokofiev were performed, frequently. In 1958, the Orchestra commissioned Sir William Walton’s Partita for Orchestra in celebration of its fortieth anniversary season. Similarly, Szell commissioned Métaboles by the French composer, Henri Dutilleux (1916-2013). At moments, we hear the influence of jazz in this music. In his program notes, Dutilleux wrote,

The rhetorical term Métaboles, applied to a musical form, reveals my intention: to present one or several ideas in a different order and from different angles, until, by successive stages, they are made to change character completely.

Here is a recording of the world premiere performance on January 14, 1965:

So let me urge you to consider that the composer is the alpha and the omega of everything we are doing, and our devotion to him must express itself in our endeavor to transmit his message—to communicate his message—which we can do only if we understand his message…. And I would like to say that in my life as a performing musician, the happiest moments were those where I had the feeling that I had approached to a certain degree the way to the goal of really understanding and transmitting the message of the composer.

– George Szell at Oberlin College, 1964

Recordings and Links

- Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major, “The Great,” d. 944, George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra Amazon

- Dvořák: Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88, George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra Amazon

- Wagner: Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey, from Götterdämmerung, George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra Amazon

- Strauss: Tod und Verklärung, Op. 24, George Szell Cleveland Orchestra Amazon

- George Szell discusses recordings and the influence of Richard Strauss on his conducting

- George Szell in rehearsal

His recordings of the Beethoven Piano Concertos with Leon Fleisher have long been my favorites.

Szell’s recorded Haydn symphonies 88, 92 through 99 and 104. Of these, my favorites 92, 93 and 95. Had he lived longer, I suspect he would have recorded all of the “London Symphonies”. His Haydn was truly magnificent with superior playing and great warmth. Unlike some conductors, Szell did not set out to prove anything with his Haydn. He just produced wonderful performances.

You are SO right! Szell enjoyed, was never apologetic about, Hayden’s humor, sometimes witty, sometimes crude and raw. His wind/brass/timpani vs strings balance was also impeccably rugged.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 with Judith Raskin. Szell’s personal property, no one ever needs to record that one again.

Dvořák 7 and Dvořák 8: Same for sure!

Incidentally, few know it, and no one talks about it, but the Jewish-American conductor was a practicing Catholic.

He went to Mass on Sundays at Communion of Saints Church, f/k/a St. Ann Church, at the corner of Coventry Road and Cedar Road in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

A friend whose father was his final doctor mentioned that Szell had “last rites.” He indeed was a Catholic and his grave has a cross on it.

Szell’s greatest recording IMO was Walton Symphony No. 2, which I consider one of the greatest recurved made. Hearing Szell’s recording makes me puzzled why it is not a work in the repertoire.