Last month, we began working our way through Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos. Today’s post continues the series. Follow these links to revisit the First and Second Concertos.

They’re now regarded as some of the most exceptional and groundbreaking works to come out of the Baroque period. But J.S. Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos were initially the result of an unsuccessful job search.

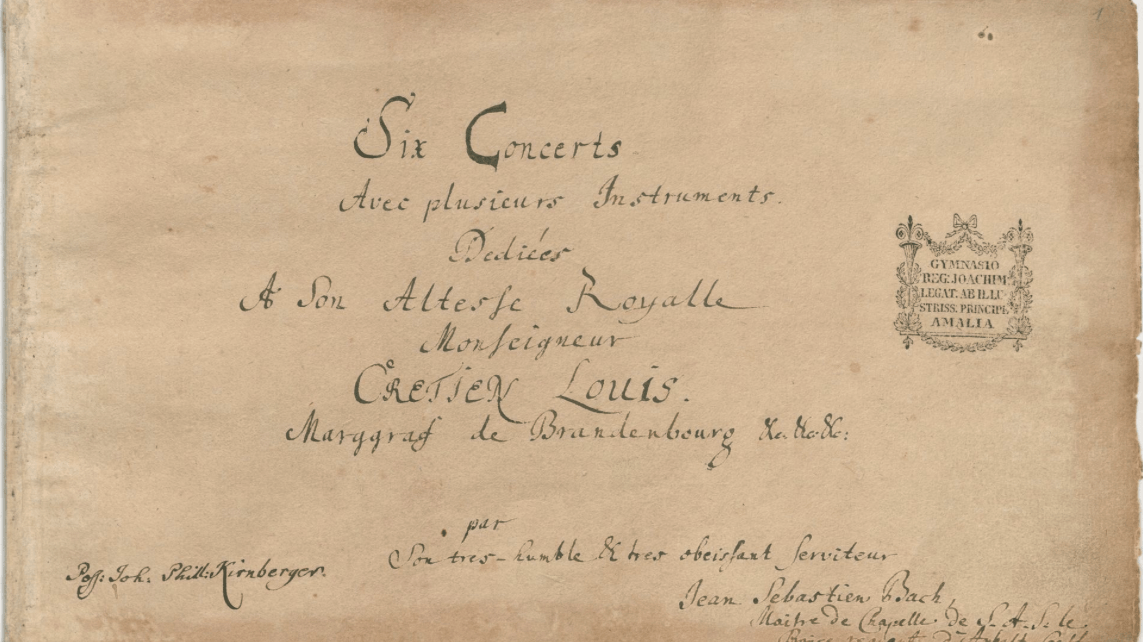

In 1721, Bach was employed as music director for Prince Leopold of Anthalt-Cöthen. When it became clear that the Prince’s new wife was not a music lover, Bach began to look for other employment. The Brandenburg Concertos, probably composed earlier, were bundled into a kind of musical résumé. As far as we know, the intended recipient, Prince Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg, never responded to Bach and may not have opened the bundle. Regardless, the musicians of his court were less skilled and would have struggled to meet the virtuosic requirements of the Brandenburg Concertos.

These are not concertos by the nineteenth century definition (a solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment). Instead, they are examples of the baroque concerto grosso, in which groups of conversing solo voices alternate with the full ensemble. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos were influenced by Vivaldi’s L’estro armonico, a set of twelve concertos Bach first heard in 1713. Yet Bach’s Concertos transcend all preexisting models. They push the form to its limits, opening up exciting and innovative new doors. The magic which unfolds in these concertos is something akin to the way Beethoven’s Eroica revolutionized the symphony. Sir John Eliot Gardiner writes,

What to me is so striking about the Brandenburg Concertos is the way Bach takes an up-to-the-minute genre—the ritornello form of the concerto pioneered and patented by the Italians of Vivaldi’s generation—and turns its conventions on their heads. Put simply, he teases us, the listeners, by setting up certain expectations of pattern and phrase-length and confounds them through his unpredictable and unconventional realisation.

In each of the six Concertos, a new and unusual combination of voices takes the stage. Concerto No. 3 in G Major is scored for three violins, three violas, and three cellos with continuo. In the first movement (beginning around the 0:19 mark), listen to the way each distinct group emerges, following the full ensemble’s spirited opening statement. They converse and overlap in an exuberant dialogue, with each section getting its moment of prominence. Near the end of the first movement, I love the way we turn a harmonic corner and suddenly find ourselves in a frighteningly unfamiliar new place. The tension rises as the short motive is repeated by each group. Then, after all of these adventures, comes a triumphant homecoming.

For the second movement of the Concerto, Bach left a single measure with only two cadential chords. Perhaps this set the stage for an improvised harpsichord or violin cadenza. Sometimes, another of Bach’s slow movements is inserted. Both solutions honor the freedom and spontaneity of performance practice in the Baroque period. Trevor Pinnock’s 2007 recording with the European Brandenburg Ensemble features an improvisation by violinist Kati Debretzeni:

Sparks fly in the exhilarating and virtuosic final movement- a wild and fun gigue-like dance. Listen to the way the opening ritornello (a recurring passage) is joyfully repeated by each new group, as if to say, “I can do that too!” Beginning at 0:28 seconds, notice the ascending violin line which leaps out of the texture.

Five Great Recordings

- Trevor Pinnock and the European Brandenburg Ensemble Amazon (This 2007 recording is featured, above).

- John Eliot Gardiner and the English Baroque Soloists

- Freiburger Barockorchester (live performance)

- Akademie fur Alte Musik Berlin

- Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert (1982)