Last month, we began working our way through Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos. Today’s post continues the series. Follow these links to revisit the First, Second, and Third Concertos.

In each of Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos we meet a different cast of musical characters. The First Concerto opens the door in magnificent style with a large, “symphonic” group, including horns with their connotations of the hunt. The Second brings high voices to the forefront with recorder, oboe, violin, and trumpet lines which soar exuberantly into the stratosphere. In the Third, the strings weave a thrilling counterpoint.

It’s important to remember that these are not concertos in the nineteenth century sense, in which a single instrument is set against the full orchestra. Instead they are examples of the baroque concerto grosso where groups of solo instruments alternate with the full ensemble. In the Brandenburg Concertos, Bach took the concerto grosso model, developed by Vivaldi and his Italian counterparts, to new heights.

In Concerto No. 4 in G Major, a new, intimate combination of solo voices take the stage. The violin and two recorders (described in the original score as “fiauti d’echo”) form a sunny, almost naively endearing trio. The atmosphere of this piece is joyful, buoyant, and virtuosic.

Following the first movement’s opening ritornello (the recurring tutti section) the violin takes center stage with an extended statement. As the movement progresses, the violin interjects with increasing virtuosic exuberance. (Notice the violin’s wild scales as the ritornello returns around the 2:53 mark). A magical and vivacious conversation unfolds:

In the second movement, the violin steps into the background and the two recorders become more prominent. We move into more solemn, contemplative territory with a sighing, E minor sarabande. From the opening bars, listen to the back-and-forth between full orchestra and the sudden lonely lament of the solo voices. Notice the extraordinary moment at 2:34 when the basso continuo comes to the melodic forefront, forming a brief duet with the recorder.

The final movement begins with a fugue subject, initiated by the violas. Listen to the way this theme is passed from one voice to another with an increasing sense of celebration and joy. Amid all of this complex counterpoint, the violin interjects passages of sparkling, unabashed virtuosity. Just before the final cadence, the party comes to a halt with two pauses. Imagine a room full of boisterous people whose divergent attention is suddenly thrust into collective focus. This music is pure fun:

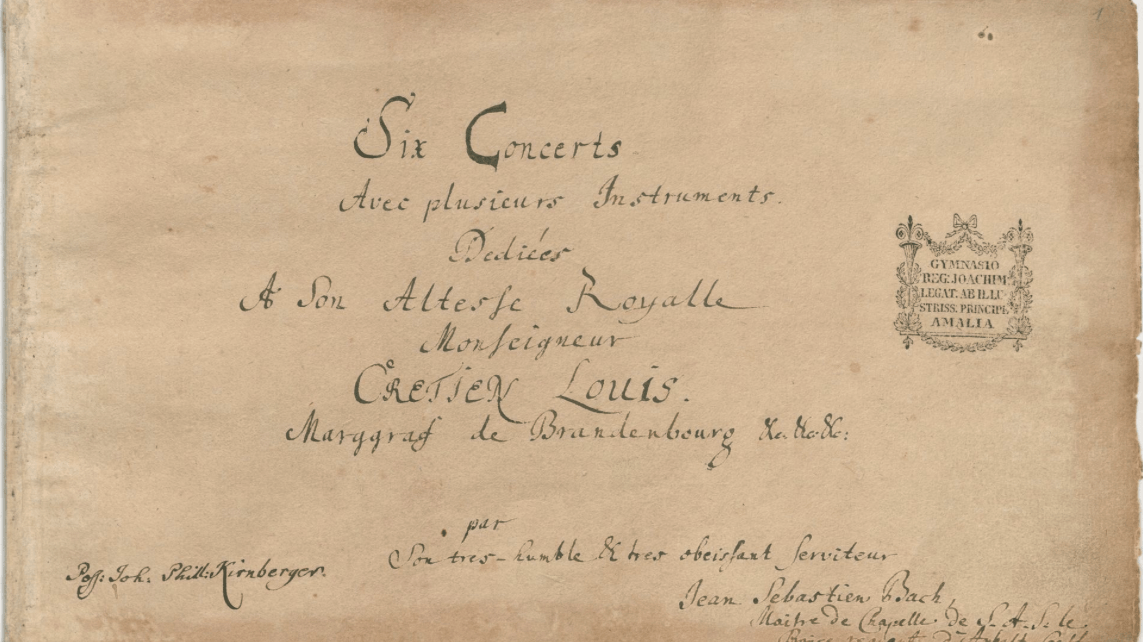

Amazingly, Bach compiled the six groundbreaking Brandenburg Concertos in 1721 as a kind of musical résumé for an unsuccessful job inquiry. Their recipient, Prince Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg, never responded and may not have opened the bundle of scores. The backstory seems inconsequential today, as this music continues to come to life for us.

Five Great Recordings

- Trevor Pinnock and the European Brandenburg Ensemble Amazon (This 2007 recording is featured, above).

- Freiburger Barockorchester (live performance)

- Cappella Gabetta (live performance)

- Oregon Bach Festival Chamber Orchestra

- Netherlands Bach Society