For several days drums and trumpets in the key of C have been sounding in my mind. I have no idea what will come of it.

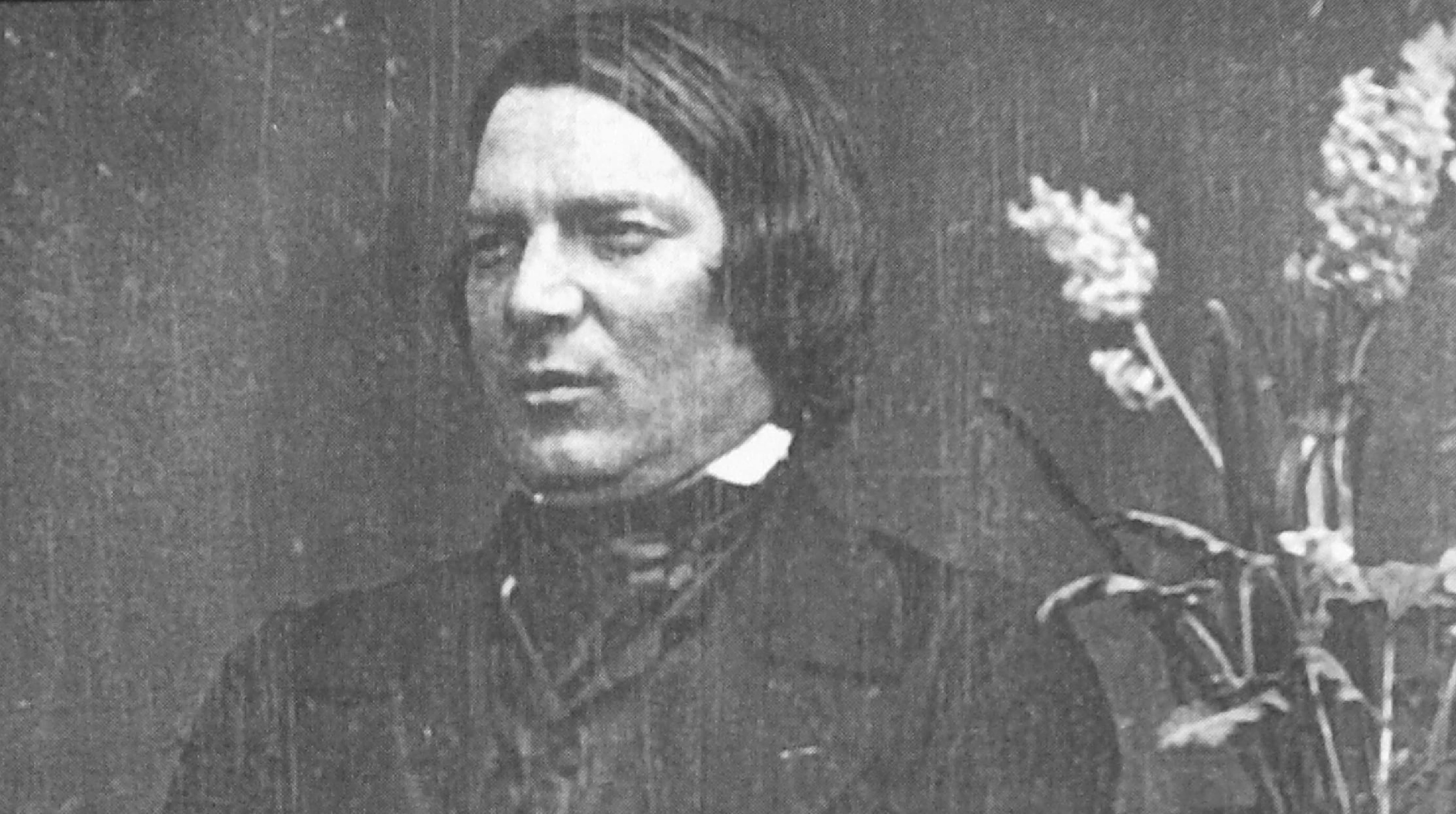

Robert Schumann wrote these words to his friend, Felix Mendelssohn, in September, 1845. We know now that the musical voices playing in Schumann’s mind were the first echoes of the Symphony No. 2 in C Major. (Actually, it would be Schumann’s third completed symphony. The D minor Symphony, completed in 1841, would be heavily revised and published as Symphony No. 4 in 1851). Mendelssohn led the premiere at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on November 5, 1846.

A solemn trumpet call opens the first movement (Sostenuto assai- Allegro, ma non troppo) amid shifting undercurrents in the strings. There is something restless and unstable about this mysterious opening. We feel as if we’ve joined music already in progress, with the trumpet motive (which enters alone on beat one) and the strings floating past each other as independent strands of sound. This foggy and uncertain opening initiates a great symphonic journey which culminates in ultimate triumph in the final movement’s coda. The trumpet’s majestic fanfare statement is the seed out of which the entire Symphony develops. Thematically, this motive might remind you of the opening of Haydn’s final Symphony, No. 104. We hear this statement, which is imprinted into the DNA of the introduction, return as a persistent presence throughout the Symphony— in the codas of the first and second movements and, finally, in the transcendent finale.

As we move into the exposition’s first theme, notice the obsessive repetition of the double-dotted rhythmic motive. There is something simultaneously noble, dancelike, and delightfully deranged about this motive, which at one point spins off into a dialogue between the strings and winds. The development section begins with a sudden harmonic turn. Listen to the way the motives of the exposition are thrown together, tossing and turning in an exhilarating, unfolding process which leads to a return home with the recapitulation.

Echoes of Beethoven can be heard in this music. There is also the strong influence of Schubert’s Ninth Symphony (also in C), with its dialogue between “choirs” of instruments (strings vs. winds, for example), and exuberantly repeating triplets in the winds and brass. (Schumann and Mendelssohn were instrumental in the rediscovery of Schubert’s forgotten final symphony). Interestingly, we also hear foreshadowings of the yet-to-be-written Brahms symphonies. (This might remind you of a similar passage in Brahms’ First Symphony. Or listen to this moment earlier in the movement).

The second movement (Scherzo: Allegro vivace) gives us a dose of effervescent Mendelssohnian lightness. (The first violin part is on almost every professional orchestra audition list). Its scurrying lines develop out of similar passages from the first movement’s coda. This Scherzo, in duple meter rather than the more standard triple meter, contains two contrasting trio sections. The second trio contains a fascinating musical cryptogram. The motive is made up of notes that spell the name of B-A-C-H in the German notation (B-flat-A-C-B). Around this time, Schumann embarked on an extensive study of Bach’s counterpoint and completed his Six Fugues on Bach, Op. 60 for organ. With its rapid walking bass line and weaving contrapuntal lines, it is easy to hear this trio as an homage to Bach.

The third movement (Adagio espressivo) is filled with long, sensuously expansive phrases, strange harmonic turns, and haunting mystery. Listen to the way the opening intervals evoke a sense of longing which only increases with statements by the solo oboe and bassoon. Just when we think we’re reaching a decisive cadence, listen to the way the music reaches higher, soaring passionately before falling back into the shadows. A moment later, fugal counterpoint brings us back to the world of Bach. The sense of suspended tension in the harmony at 26:53 almost seems to anticipate Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, as do the overlapping voices a moment later when the violins dissolve into descending trills and the woodwinds pick up the melodic line.

The final movement (Allegro molto vivace) kicks off with a flourish. With spirited, feisty energy, the winds state the main theme in the “wrong” key before being pulled forcefully into the “correct” key by the full orchestra. This motive contains vague echoes of the sunny opening of Mendelssohn’s “Italian” Symphony. A reference to the third movement’s main theme returns in the solo clarinet (31:42). In Wednesday’s post, we listened to the final song from Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved), Op. 98 cycle, and explored the way its main motive emerges in several of Schumann’s works. In this final movement, following a shadowy C minor cadence, the “Beethoven motive” propels the music forward towards its triumphant conclusion. In its joyful final moments, the Second Symphony achieves a remarkable and visceral sense of motion and majestic grandeur. The “trumpets and drums” which played in Schumann’s mind are set free.

Five Great Recordings

- Schumann: Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61 Christoph von Dohnányi, Cleveland Orchestra Amazon

- George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra (1958 studio recording)

- Leonard Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic (concert clip)

- Paavo Järvi and the Staatskapelle Dresden

- Kenneth Woods and the Orchestra of the Swan

Sorry that you had problems submitting this comment, Lee. If others are having problems with the comment form please let me know!

Great article! But you haven’t heard the Sawallisch recording with the Dresdeners?