Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9, Op. 47—better known as the “Kreutzer” Sonata—was first performed on May 24, 1803.

216 years ago today, Beethoven and the Afro-European violinist George Bridgetower (1778-1860) premiered this convention-shattering music at Vienna’s Augarten Theatre. Beethoven was so late in completing the manuscript that Bridgetower was forced to sightread the performance, at times looking over the composer’s shoulder at the full score. Originally, the manuscript was inscribed with the lighthearted dedication to Bridgetower, “Sonata per un mulattico lunatico.” But, as the story goes, Beethoven later broke off all relations with Bridgetower after the violinist allegedly insulted a woman whom Beethoven admired. The original dedication was replaced with a dedication to the esteemed French violinist, Rodolphe Kreutzer who never performed it and called the piece “outrageously unintelligible.”

Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Rita Dove dramatizes the relationship between Beethoven and Bridgetower in her lyric narrative, Sonata Mulattica. Leo Tolstoy also referenced the piece in the 1889 novella, The Kreutzer Sonata.

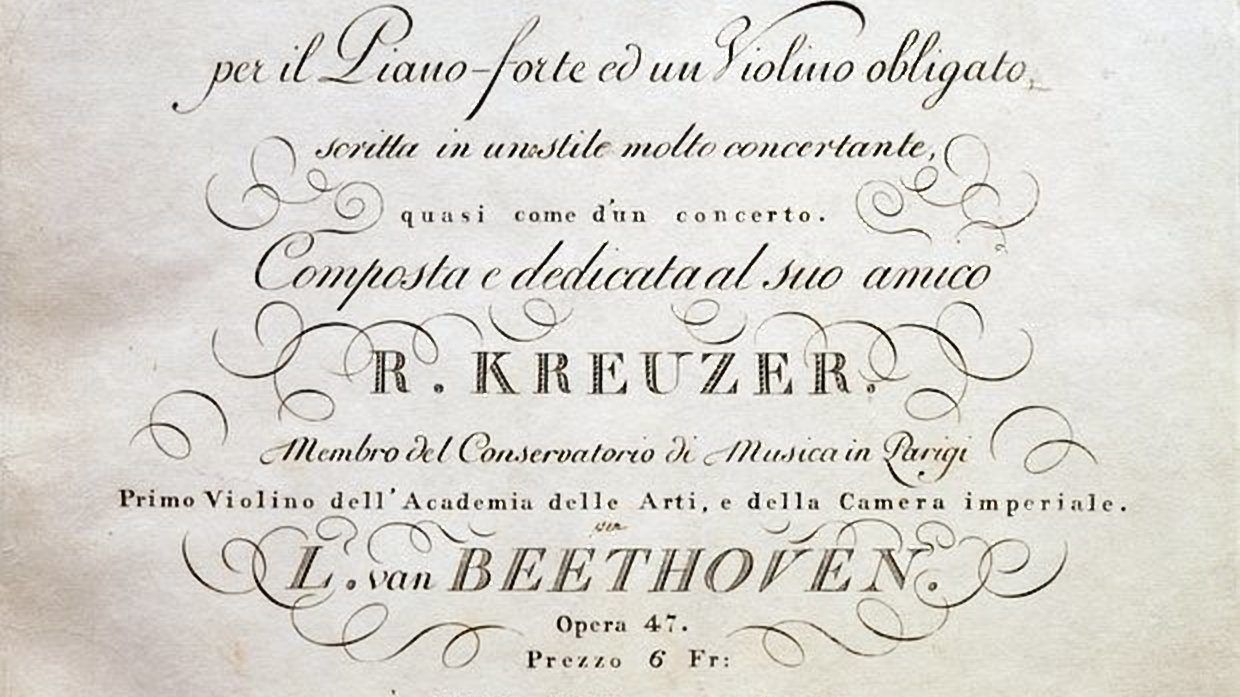

From the cosmic Ninth Symphony with its operatic associations and mighty chorus, to the otherworldly transcendence of the late string quartets, Beethoven’s music often seems to burst out of the confines of genre, style, and convention. It’s as if the music is too vast, ferocious, and timeless to be contained or classified. Listening to the “Kreutzer” Sonata, it’s easy to come away with this sense of awe. Beethoven’s description in his sketchbook suggests music in which a concerto has assumed the identity of a sonata: “Sonata per il Pianoforte ed uno violino obligato in uno stile molto concertante come d’un concerto.”

The violin’s solo chords in the first movement’s opening introduction (Adagio Sostenuto) tell us, immediately, that this is no typical sonata. The piano answers, pulling the music away from its home key of A major towards a darker minor and beyond. A conversation unfolds between the two equal voices. It’s what the commentator Robert Kapilow describes as “a collaboration in search for a connection.” As Kapilow points out, the half step becomes the seed out of which the entire first movement develops:

This is the creation of a universe…What can I make now that we’ve reduced the world down to an atom of just up a half-step or down a half-step? He finally discovers one more half-step up. And those two notes—E and F—are the cornerstone of the whole universe. He’s literally derived it for us from that ending.

The second movement (Andante con Variazioni) is a set of magical and adventurous variations on a noble and lamenting theme. It’s a melody which seems to begin in mid phrase, wandering down and back up. As with many of Beethoven’s melodies, this expansive theme is made up of a series of small motivic cells. After frolicking through several ebullient variations, the music falls into an atmosphere of quiet, dreamy serenity.

The final movement (Presto) follows the rhythmic pattern of a tarantella–the rapid dance originating in Italy which, according to legend, served as an emergency “cure” for the poisonous bite of the tarantula spider. This wild tarantella is set in motion by a massive and jarring A major chord which rudely wakes us from the second movement’s dreamscape. An exuberant musical conversation unfolds amid jubilant splashes of virtuosity and sudden, carefree modulations. Throughout this playful and unabashed movement, listen for those sudden moments of quiet, tender intimacy.

Here are five contrasting interpretations of the “Kreutzer” Sonata. Share your thoughts, as well as your own favorite recordings, in the comment thread, below.

Gidon Kremer and Martha Argerich

David Oistrakh and Lev Oborin

Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Fazıl Say

Pinchas Zukerman and Daniel Barenboim

Arthur Grumiaux and Clara Haskil

Recordings

- Gidon Kremer and Martha Argerich (1995 recording) Amazon

- David Oistrakh and Lev Oborin Amazon

- Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Fazıl Say (2008 recording) Amazon

- Pinchas Zukerman and Daniel Barenboim (1973 recording) Amazon

- Arthur Grumiaux and Clara Haskil (1957 recording) Amazon

Photograph: The front page of an original edition of the Kreutzer Sonata

Great post. You may wish to check out these striking personalities:

Patricia Kopatchinskaja & Fazıl Say play this – you can check them out on YouTube.

https://youtu.be/OF9fneQ50Us

This performance is among those above, and yes it does have an extraordinary electricity!

Two other worthy recordings, imho, are these:

Isabelle Faust (violin) and Alexander Melnikov (piano)

Itzhak Perlman (violin) and Martha Argerich (piano)

Another favorite of mine is Itzhak Perlman (violin) and Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano).

They display a fusion that’s very differnt from the dynamic conflict of Kremer and Argerich.

Kavakos and Pace were nominated for a Grammy for their Beethoven sonatas and their Kreutzer sonata is on par with all these mentioned. The violin better than all 4. The piano impeccable

My favorite still is by Jascha Heitfetz and Erik Friedman.