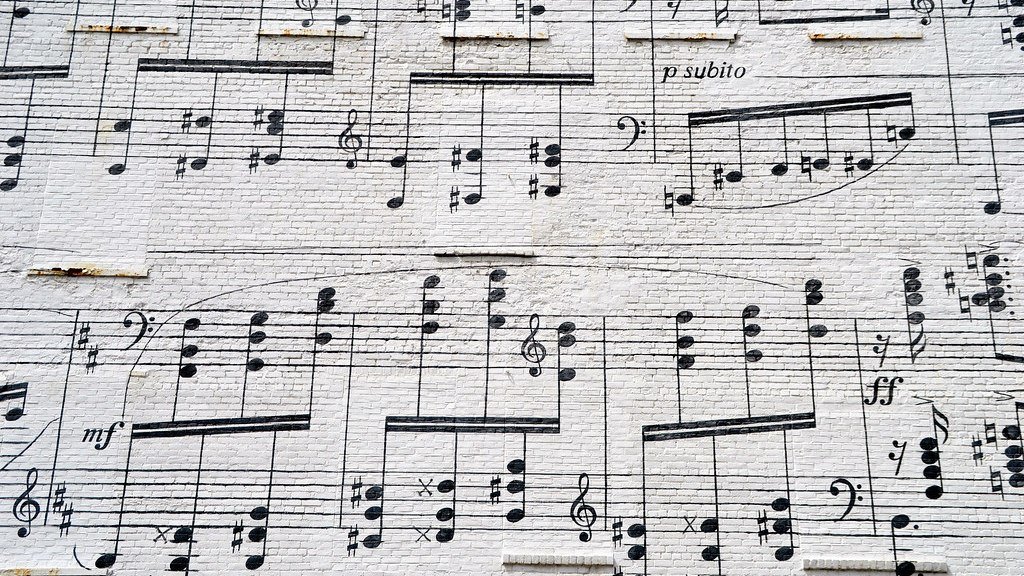

Sometimes the notation of a musical score becomes a work of art in its own right. Such is the case with a vast mural painted in the early 1970s on the exposed brick wall of the Schmitt Music Company building in downtown Minneapolis (pictured above). The mural was created after Minneapolis Star columnist Barbara Flanagan called out the blank wall’s unsightliness. “You need to make that wall sing,” she wrote.

The three-story-tall mural which sings out over a parking lot depicts a page from the score of Scarbo, the final movement of Maurice Ravel’s 1908 solo piano suite, Gaspard de la nuit. These exuberant notes add up to some of the most ferociously difficult music ever written for the piano. The pianist Steven Osborne has compared playing this piece with “having to solve endless quadratic equations in my head.” In his 2004 article, Alexander Eccles compares the suite to “a realistic dream, a lucid world of darkness and terror evoked through refinement and detail.”

Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit was inspired by a similarly titled book of poems and drawings by Aloysius Bertrand, published in 1842. The book is filled with nightmarish, hallucinatory fantasies similar to the work of Edgar Allan Poe. Bertrand suggested that Satan, going by the pseudonym “Gaspard” (translation from Persian: “a man who guards mysterious, jewel-like treasure”) was the true author of the collection. After the struggle of composing the piece, Ravel said, “Gaspard has been a devil in coming, but that is only logical since it was he who is the author of the poems.”

The first movement, Ondine, evokes the shimmering splashes and flowing current of water. In Bertrand’s poem, a beautiful water nymph attempts to seduce a man. When he rejects her, explaining that he is married to a mortal, she “dissolves in tears and laughter” and evaporates like a fleeting dream. Throughout this movement, I can’t help hearing echoes of the haunting theme from the final movement of Debussy’s La Mer, completed three years earlier in 1905, which begins with a longing minor second followed by the interval of a major second.

The second movement, Le Gibet, relates to the image of the solitary corpse of a hanged man on a gibbet in the middle of a desolate desert landscape. A reddish, setting sun descends on the horizon. The tolling bells of a distant walled city can be heard in the haunting persistence of a B-flat ostinato. Time seems to stand still. This is music filled with mystery and lament. Harmonically, there are some fascinating hints of jazz.

The final movement, Scarbo, erupts with demonic virtuosity. We hear the influence of Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Études. Ravel clearly wanted to push the piano to its technical limits as Liszt had, even admitting that he attempted to exceed the technical demands of the Russian composer Mily Balakirev’s treacherous “Oriental Fantasy,” Islamey. Describing the movement’s Lisztian bravura, Ravel said, “I wanted to make a caricature of romanticism. Perhaps it got the better of me.” The poem depicts a mischievous goblin who appears in the dead of night and plays terrifying tricks on the mind of the narrator as he lies in bed.

Ravel was a composer who frequently transferred piano scores to the rich color palette of the full orchestra. Although the conductor Eugene Goossens orchestrated Gaspard de la nuit in 1942, Ravel left the work to stand in its solo piano form. Within the solo piano lines of Scarbo, we get the sense that a rich array of orchestral voices are conversing. Regarding this final movement, Ravel said, “I wanted to write an orchestral transcription for the piano.”

Here is an extraordinary 1992 recording featuring Jean-Yves Thibaudet:

I. Ondine

II. Le Gibet

III. Scarbo

Recordings

- Ravel: Gaspard de la nuit, M.55, Jean-Yves Thibaudet Amazon

- a 2003 recording featuring Jean-Efflam Bavouzet

- Martha Argerich’s live 1972 recording

Excellent enlightenment! I knew nothing of the mural and am pleased to learn of Aloysius Bertrand. Thank you.

thank you so much ! re info on Gaspard de la Nuit and recordings

I had heard Martha Argerich’s recording of this piece , but Jean-Yves’ rendition is right up there with her. I would have to listen to them back to back to see if either is better than the other, but there’s no doubt that Thibaudet is a master of the French impressionists.