Beethoven’s First Symphony springs to life as a frolicking newcomer, teeming with audacious youthful vitality. Premiering at Vienna’s Burgtheater on April 2, 1800, it seems to say goodbye to one century, while eagerly anticipating another. “This was the most interesting concert in a very long time,” reported the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, Germany’s foremost musical periodical at the time. The review noted the work’s “considerable art, novelty and wealth of ideas.”

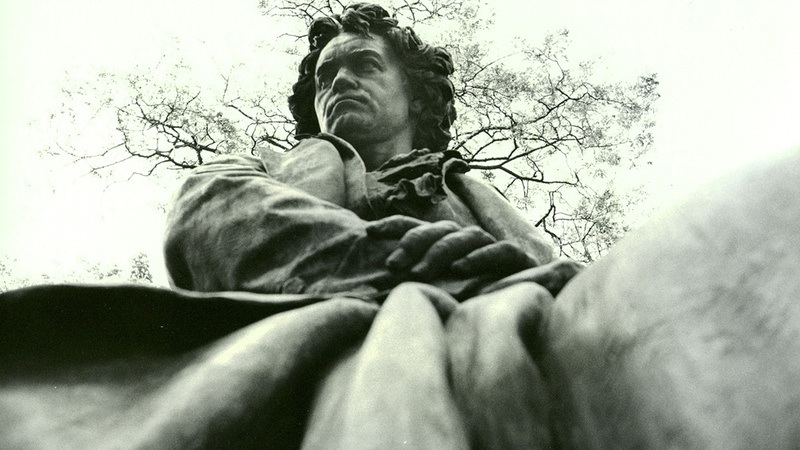

Make no mistake, Beethoven’s First is still a profoundly classical symphony. The influence of Haydn and Mozart is palpable. Haydn, who taught the rebellious young Beethoven, had completed his final Symphony (No. 104) five years earlier, while Mozart’s monumental “Jupiter” Symphony was already twelve years old. Beethoven’s First Symphony, set in the pure, wide-open key of C major, contains none of the jarring, revolutionary fire of the composer’s later symphonies, such as the “Eroica.” Yet, listening to this music, you can tell that something new is in the air. Beethoven’s distinctive voice is evident. This is the symphony of a giant, boldly taking his place among other giants.

The first convention-shattering moment comes with the Symphony’s opening. Audiences in 1800 might have expected the piece to begin with a forceful musical “call to order”—something left over from the days when unruly opera audiences needed to be quieted down. For example, listen to the way the opening of Haydn’s Symphony No. 102 simultaneously grabs our attention and establishes the home key, with deep octave B-flats throughout the entire orchestra. Instead, Beethoven’s twelve-measure introduction begins in the “wrong” place, with a series of dominant-tonic chord sequences that give us no sense of the home key. The first resolution outlines F major, the second only hints at C, and the third leads to G major. Only gradually, does the music find its way out of the weeds. One critic who attended the premiere wrote, “Such a beginning is not suitable for the opening of a grand concert in a spacious opera house.”

The music which follows is filled with sudden modulations, abrupt changes in dynamic, and the sting of Beethoven’s trademark sforzandos. An exuberant conversation unfolds between “choirs” of instruments. Just listen to the thrilling weave of voices in this passage from early in the exposition section. The sense of dialogue among this vast cast of musical characters is almost dizzying. In its review, the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung was baffled by “the excessive use of wind instruments, so that there was more Harmonie (wind ensemble) than orchestral music as a whole.” As the first movement’s coda section draws to a close with a sustained celebration of C major in the winds, you can almost hear the seeds of the triumphant final movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

The second movement (Andante cantabile con moto) ushers in a graceful and charming dancelike melody in 3/8 time. First, we hear it in a single, unassuming voice. Then, another voice enters…then a third, and finally the entire movement blossoms. Here, Beethoven again shatters the conventions of the classical symphony by using the full orchestra, rather than retreating into the intimacy of reduced forces. Throughout the second movement, notice all of the rhythmic tricks which occasionally throw off our sense of the three underlying beats in each measure.

The third movement is called a “Minuet.” But as the opening bars launch into motion, we realize that we’re far removed from the elegant, stately minuet third movements of Haydn’s symphonies. It’s almost as if the young Beethoven is playing an irreverent practical joke, shattering our expectations, and laughing along the way. What we get is actually a thundering scherzo, filled with wild shifts in the tonal center, sudden ferocious jabs, and trumpet fanfares.

The final movement (Allegro molto e vivace) begins with the kind of musical “call to order” which might have opened the first movement. Then, in the ultimate musical tease, a tentative, ascending three note fragment rises in the violins. We soon realize that a simple scale is being constructed, one note at a time. Then, we’re off and running. Amid wildly swirling scales, the First Symphony concludes with the ultimate infectious humor and fun.

Five Great Recordings

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21, Riccardo Chailly, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra Amazon

- Christopher Hogwood and The Academy of Ancient Music

- Sir John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique

- Leonard Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic

- Arturo Toscanini and the BBC Symphony Orchestra