Guillaume Tell, which premiered in 1829, was the last of Gioachino Rossini’s 39 operas. Its four acts tell the story of the revolutionary folk hero William Tell who, with the expert use of his bow and arrow, launched the struggle for Swiss independence from Austria. Donizetti once proclaimed that the opera’s second act was so sublime that it had been composed not by Rossini but by God. The complete opera is rarely performed now. But the overture stands as one of the most iconic works ever written.

Thanks to its use in the 1950s television drama, The Lone Ranger, the Overture’s galloping final section is instantly recognizable. In the context of the opera, this section represents “the Swiss soldiers’ victorious battle to liberate their homeland from Austrian repression.” There is something equally extraordinary about the way the Overture begins. Evoking a spellbinding dawn, a longing melody unfolds in a choir of five solo cellos. Berlioz wrote that this introduction “suggests the calm of profound solitude, the solemn silence of nature when the elements and human passions are at rest.” Rossini’s use of a cello choir influenced similar passages in later Italian operas, perhaps most notably the love duet, Già nella notte densa, from Act I of Verdi’s Otello.

The Overture’s interior sections might remind you of the nature-inspired scenes of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony. Following the turbulence of a storm, we find ourselves in the tranquility of an Alpine pasture with the herdsmen’s melody, Ranz des Vaches, in the English horn. Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, with its mournful, distant offstage English horn was first performed a year after Guillaume Tell in 1830. In the Overture of Wagner’s 1843 opera, The Flying Dutchman, the “love and redemption” theme is heard in a similarly bucolic English horn solo.

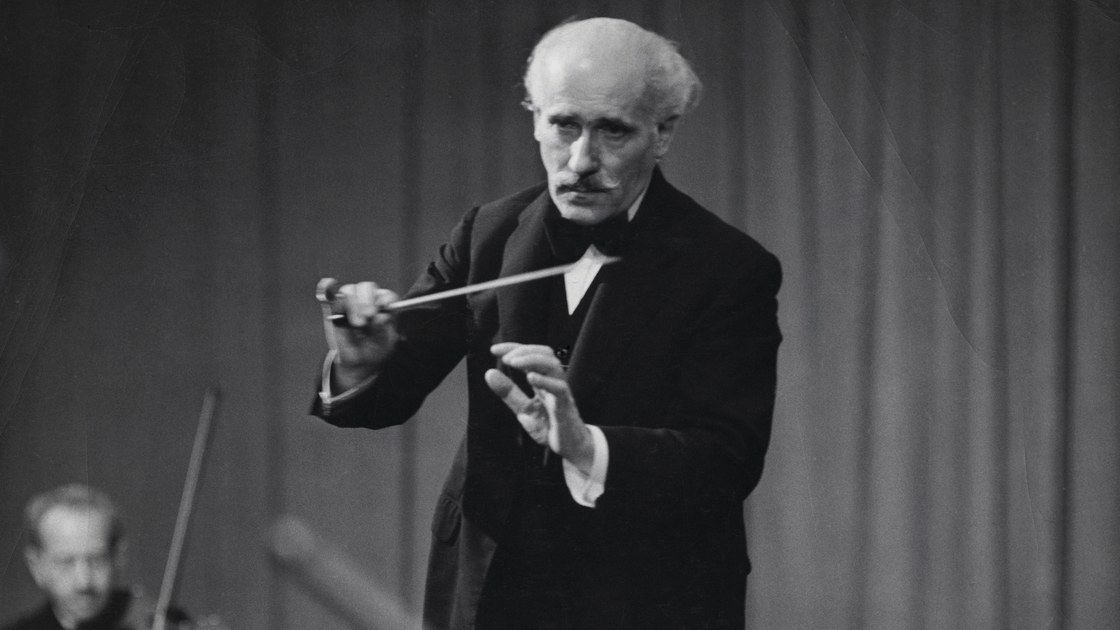

Here is a video clip of a performance given by the 85-year-old Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall on March 15, 1952. We get an intimate look at the laser precision of Toscanini’s conducting, and the exhilarating result from the orchestra:

Recordings

- Rossini: William Tell Overture, Arturo Toscanini, NBC Symphony Orchestra Naxos Records

I’m not a musician, but I listen many types of music and a lot of classics. I often compare Toscanini’s rendition of The William Tell Overture to other conductor’s. Consequently, I have questions.

1. Toscanini uses a cello duet at the very beginning instead of the solo that was written. The result is wonderful, but did this cause any public stir at the time?

2. The conductors of today have changed the last note of the 33rd bar of the Ranz des vaches to a B instead of the A, that was originally written. Why did this come about?