Stephen Sondheim’s grisly 1979 musical thriller, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, tells a story of blood-soaked, all-consuming revenge which ends in self-annihilation.

The action is set in 1845, amid the gloom and hellish alienation of rapidly industrializing Victorian London. The barber, Sweeney Todd, has returned to London from exile in Australia. He was sent there on false charges by the corrupt Judge Turpin, who with the help of Beadle Bamford, tormented and raped Sweeney’s wife, Lucy. The vengeful Sweeney is determined to get the unsuspecting Judge into his barber’s chair, where he promises to give the ultimate close shave. Along the way, Sweeney’s razor gets plenty of practice on other victims. A darkly symbiotic relationship develops between the demonic barber and his downstairs neighbor, Mrs. Lovett, whose filthy pie shop was previously short of meat.

Sweeney Todd alternates abruptly between chilling terror and gruesome humor. The cast steps out of the drama to function as a Greek chorus in the recurring Ballad of Sweeney Todd, which delivers the earthy punch of early rock and roll. Sondheim has said, “what the show is really about is obsession.” Beginning with The Ballad of Sweeney Todd, the orchestra lines are filled with short, obsessively repeating fragments. The presence of the Dies Irae is evident, not only in the Ballad, but throughout the score. There are echoes of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Ravel’s La Valse, and the film scores of Bernard Herrmann. Judge Trupin’s leering, lustful soliloquy, Johanna, begins and ends with a dissonant chord that Sondheim claims was used in every Herrmann score.

Stephen Sondheim has acknowledged a personal aversion to opera. He inhabits the world of musical theater, in which song and lyric exist exclusively to develop characters and further the plot. In many ways, Sweeney Todd pushes the musical to its dramatic limits. It’s the pinnacle of an evolution which began with the extended “bench scene” from the first act of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel. Yet, there are also decidedly operatic moments in Sweeney Todd. Only twenty percent of the show is spoken dialogue. The score is not a collection of insular songs, but rather a rich tapestry, woven together by a complex web of recurring motifs. At times, two, three, or four characters sing simultaneously, expressing independent inner thoughts or dialogue. This is the kind of dramatic counterpoint we find throughout opera, especially in the works of Mozart. Sweeney Todd, which Sondheim has called a “black operetta,” has moved into the opera house, with performances by such notable companies as the New York City Opera and San Francisco Opera.

My Friends

One of the first operatic moments in Sweeney Todd comes early in the first act. Mrs. Lovett, who recognizes Sweeney Todd’s true identity as the exiled Benjamin Barker, presents him with his old silver shaving razors. The first four pitches are an inversion of the Dies Irae. The music begins with a sense of quiet intimacy and wonder. Gradually, it grows into a soaring statement filled with passion and nostalgia. Yet this is a love ballad, not to a person, but to the instruments that will exact Sweeney’s revenge. Mrs. Lovett expresses her fondness for Sweeney, yet he is so absorbed that he cannot hear her. The two characters are there together, yet they are locked in separate realities. This is a duet of disconnection.

Kiss Me/Ladies In Their Sensitivities/Kiss Me (Quartet)

Anthony, a young sailer who returned to London on the same ship as Sweeney, falls in love with the beautiful Johanna. Unbeknownst to him, she is the infant daughter Sweeney Todd left behind when he went into exile. She was raised as a ward of Judge Turpin. Now, Turpin intends to marry her. In this sequence, Anthony tries to comfort the terrified Johanna by proposing a rescue plan. Meanwhile, the Beadle suggests to Judge Turpin that he should visit Sweeney Todd in order to clean up his appearance for Johanna. The piece ends as a full-blown quartet between the four characters.

Johanna (Quartet)

Sweeney Todd contains three Johanna pieces. The first is a soaring and heroic declaration of love, sung by Anthony in the first act. Its accompaniment line grows out of the church chimes that toll throughout the score. The second Johanna is Judge Turpin’s diabolical soliloquy. In the final Johanna, Sweeney attempts to escape haunting visions of his long-lost daughter. As he bids her “goodbye,” we hear the thud of bodies dropping down a chute into Mrs. Lovett’s pie shop.

In this quartet, several dramatic threads come together. The piece begins with a brief remembrance of Anthony’s yearning love song. Sweeney’s painful “goodbye” is accompanied by a dry, incessant rhythmic motor in the orchestra, punctuated by occasional icy violin harmonics. It’s music of cold detachment. As the quartet unfolds, Sweeney’s Johanna blends with Anthony’s. The Beggar Woman (actually the now insane Lucy Barker) shrieks about a “city on fire,” perhaps a statement on the foul-smelling smoke which rises from Mrs. Lovett’s chimney. Johanna’s angelic fragments from Kiss Me complete the quartet. Perhaps the entire drama of Sweeney Todd is encapsulated in this one piece.

Recordings

- Sondheim: Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (original Broadway cast album) Amazon

- Sondheim: Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (dvd of the original Broadway production) Amazon

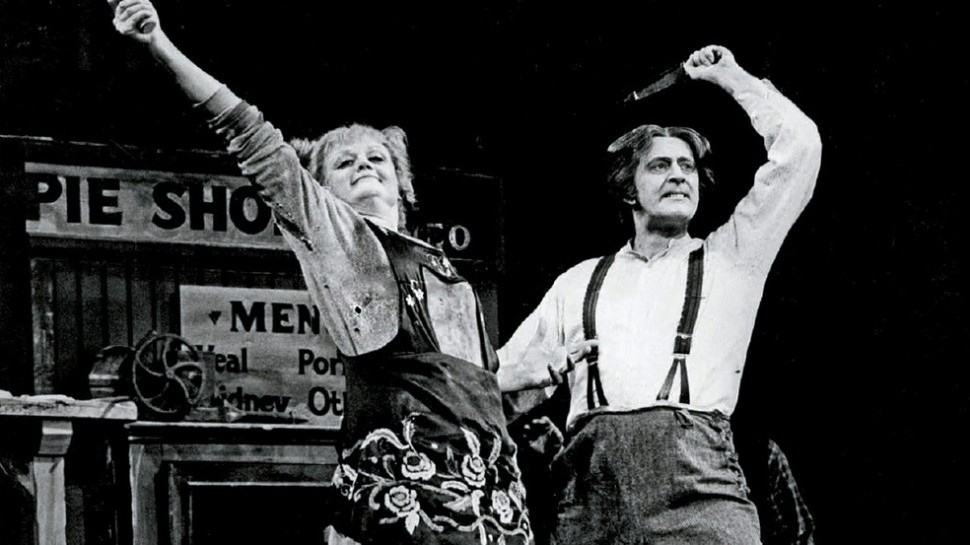

Featured Image: Angela Lansbury and Len Cariou in the original Broadway production of “Sweeney Todd”

Thank you for the insightful analysis of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. However, I have never liked nor enjoyed Stephen Sondheim’s grisly 1979 musical thriller! And I do enjoy opera!