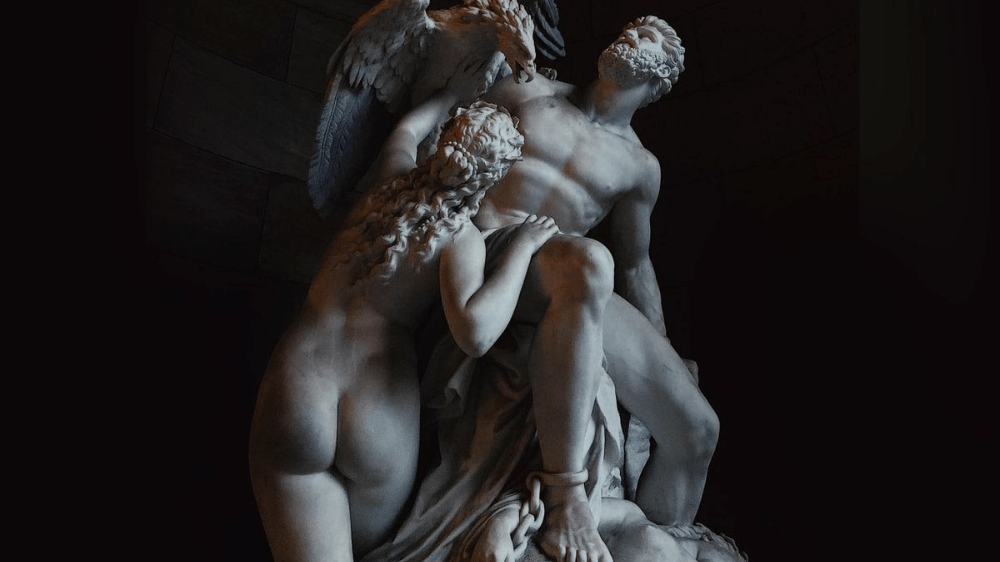

In Greek mythology, the Titan and “supreme trickster” Prometheus steals fire from the gods and brings it to humanity in defiance of Zeus.

For the Russian composer Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915), Prometheus’ fire symbolized searing creative energy and an ecstatic expansion of human consciousness. Influenced by mysticism, Theosophy, and the theories of Nietzsche, Scriabin believed that the highest calling of humanity was to escape the physical world and enter a vast “oneness” with the cosmos. The composer expressed these ideas with provocative statements such as, “I am a moment illuminating eternity…I am affirmation…I am ecstasy,” and “I am God! I am nothing, I’m play, I am freedom, I am life. I am the boundary, I am the peak.”

Scriabin believed that music held the power to unlock a transcendent level of consciousness. As a pianist-composer, he was initially influenced by the music of Chopin and Liszt. By the early years of the twentieth century, he embarked on a series of symphonic works that attempted nothing less than to open the door to the universe. The trilogy proceeded from The Divine Poem (1905), to The Poem of Ecstasy (1908), and concluded with Prometheus, The Poem of Fire (1909-1910). A final work, Mysterium, was to have been a grand, multimedia fusion encompassing all of the arts. Before the work was completed, Scriabin died of a terminal infection at the age of 43.

Prometheus, The Poem of Fire begins with a sonority which simultaneously delivers eerie status and quiet, searing intensity. Known as the “mystic chord,” it is a hexachord built on fourths (A, D-sharp, G, C-sharp, F-sharp, B). Scriabin called it “the chord of the pleroma,” suggesting the embodiment of all divinity. In the score, he described the tonal color as “smoky.” It’s a chord in which all harmonic function dissolves into pure sound.

Emerging from this strikingly cosmic chord, the work develops as a vast, gradual crescendo and acceleration. It unfolds in a single movement, suggesting an uninterrupted and timeless journey. Harmony and melody blend into one. The solo piano becomes a major protagonist, symbolizing man. The rapturous drama includes symbolic allusions to the dawn of consciousness, the creative will, and ecstatic human love. The “mystic chord” is a persistent presence. In the final moments, the orchestra is augmented by a cosmic chorus which sings only vowels. The conclusion brings a radiant F-sharp major chord.

For Scriabin, who experienced synesthesia, sound and color were inseparable. In the score for Prometheus, The Poem of Fire, he attempted to move beyond sound itself, with the inclusion of a “color organ.” Notated on a separate staff at the top of the score, harmonic changes were translated into light and color. Although Scriabin went so far as to describe the piece as “a symphony of color rays,” the color elements were not technically feasible at the time. A 2010 performance at Yale University, in collaboration with the scholar Anna Gawboy, attempted to realize something close to Scriabin’s intentions. With Prometheus, The Poem of Fire, Scriabin composed the ultimate aspirational work and grasped at the intangible.

Here is Pierre Boulez’ 1999 recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus and pianist Anatol Ugorski:

Recordings

- Scriabin: Prometheus, The Poem of Fire, Op. 60, Pierre Boulez, Anatol Ugorski, Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus Amazon

- Toshiyuki Shimada and the Yale Symphony Orchestra (presented with a lighting component based on the composer’s score)

Featured Image: Prometheus Bound and the Oceanids (1879), Eduard Müller