J.S. Bach’s monumental chamber music collection, Musikalisches Opfer (The Musical Offering), was inspired by a momentous meeting.

It began on May 7, 1747 when Bach met Frederick the Great in Potsdam. At the time, J.S Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, was employed as one of the Prussian King’s most prized musicians. Frederick gave the elder Bach a tour of his palace, showcasing his vast collection of instruments, among which was a novel new keyboard instrument, the fortepiano, built and developed by Gottfried Silbermann.

J.S. Bach’s music, with its density and complex polyphony, had already gone out of fashion, displaced by the leaner, elegant galant style championed by C.P.E Bach. Still, “the old Bach of Leipzig” was hailed as one of the greatest improvisers. Frederick gave Bach an expansive theme and challenged the master to improvise a three-voice fugue. This melancholy subject, with its distinctive descending chromatic line, is not unlike the subject of Handel’s Fugue in A Minor, HWV 609, composed in 1716. Bach was so taken with the mysterious “Royal Theme” that, upon returning home, he used it as the basis for a six-voice fugue, ten miraculous canons, and a trio sonata for flute, an instrument which Frederick the Great played proficiently. The 16 movement collection, now know as The Musical Offering, was dedicated to the King. “Frederick was sent a splendid luxury print and Bach distributed his masterpiece among his friends, despite the high costs of printing.” (Netherlands Bach Society)

The Musical Offering is filled with musical riddles and theological symbolism. The ten canons are an allusion to the Ten Commandments. Canon No. 9 bears the inscription, Quaerendo invenietis (“Seek and ye shall find” from the biblical Sermon on the Mount. The two fugues are given the title, Ricercar, a type of improvisatory composition originating in the late Renaissance which means, literally, to “seek out” the possibilities of a piece in terms of key or mode. The first letters of each word in Bach’s title for the collection, Regis Iussu Cantio Et Reliqua Canonica Arte Resoluta (the theme given by the king, with additions, resolved in canonic style) spell out Ricercar. Perhaps Frederick the Great, seduced by the styles of the times, failed to fully appreciate Bach’s collection. In reality, the aging composer’s timeless “offering” was meant for God and posterity.

Ricercar a 3

This is the three-voice fugue which opens The Musical Offering. It gives us a sense of the music Bach might have improvised when initially presented with the theme. The theme’s descending chromatic line develops into a dizzying roller coaster ride (4:17).

In this performance and the one below, Leo van Doeselaar plays the fortepiano:

Ricercar a 6

Arnold Schoenberg believed that Frederick the Great may have presented the theme to Bach as a practical joke. He may have believed that it would be impossible, even for Bach, to build a six-voice fugue on such a theme. While the Ricercar a 3 flirts with the gallant style, Ricercar a 6 represents the grand summit of polyphony.

Webern’s Orchestration

Bach’s score does not specify what instruments should play this music. In 1934, Anton Webern orchestrated the Ricercar a 6 for a chamber orchestra which included strings, solo winds, harp, and timpani. Through a technique he called Klangfarbenmelodie (“tone-color melody”), Webern transforms Bach’s fugue into technicolor. At times, a single melodic line alternates between a variety of instrumental voices. We hear each line with renewed clarity:

Sofia Gubaidulina’s Offertorium -Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

The Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina picks up where Webern left off with her violin concerto, Offertorium. The work was composed in 1980 for Gidon Kremer. It has been described as a series of variations or “an extended meditation” on the “Royal Theme” from Bach’s Musical Offering. In the opening bars, the theme is presented in its entirety, with the exception of the final note. (It is cut off by the entrance of the solo violin). As the variations unfold, the theme breaks into increasingly short fragments and eventually disintegrates into a free rhapsody. Structurally, the Concerto is set in three sections which flow together without interruption. The final moments drift into something akin to a lamenting Russian Orthodox chorale. Against a shimmering backdrop, the theme re-emerges in retrograde.

Here is Oleh Krysa’s recording with James DePreist and the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra:

Recordings

- J.S. Bach: Musical Offering, BWV 1079, Gustav Leonhardt , Robert Kohnen, Barthold Kuijken, Sigiswald Kuijken, Wieland Kuijken, Marie Leonhardt Amazon

- J.S. Bach: Musical Offering, BWV 1079, (Orch. Anton Webern) – Fuga (Ricercata) a 6 voci, Pierre Boulez, Berlin Philharmonic Amazon

- Gubaidulina: Offertorium, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Oleh Krysa, James DePreist, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra BIS Records

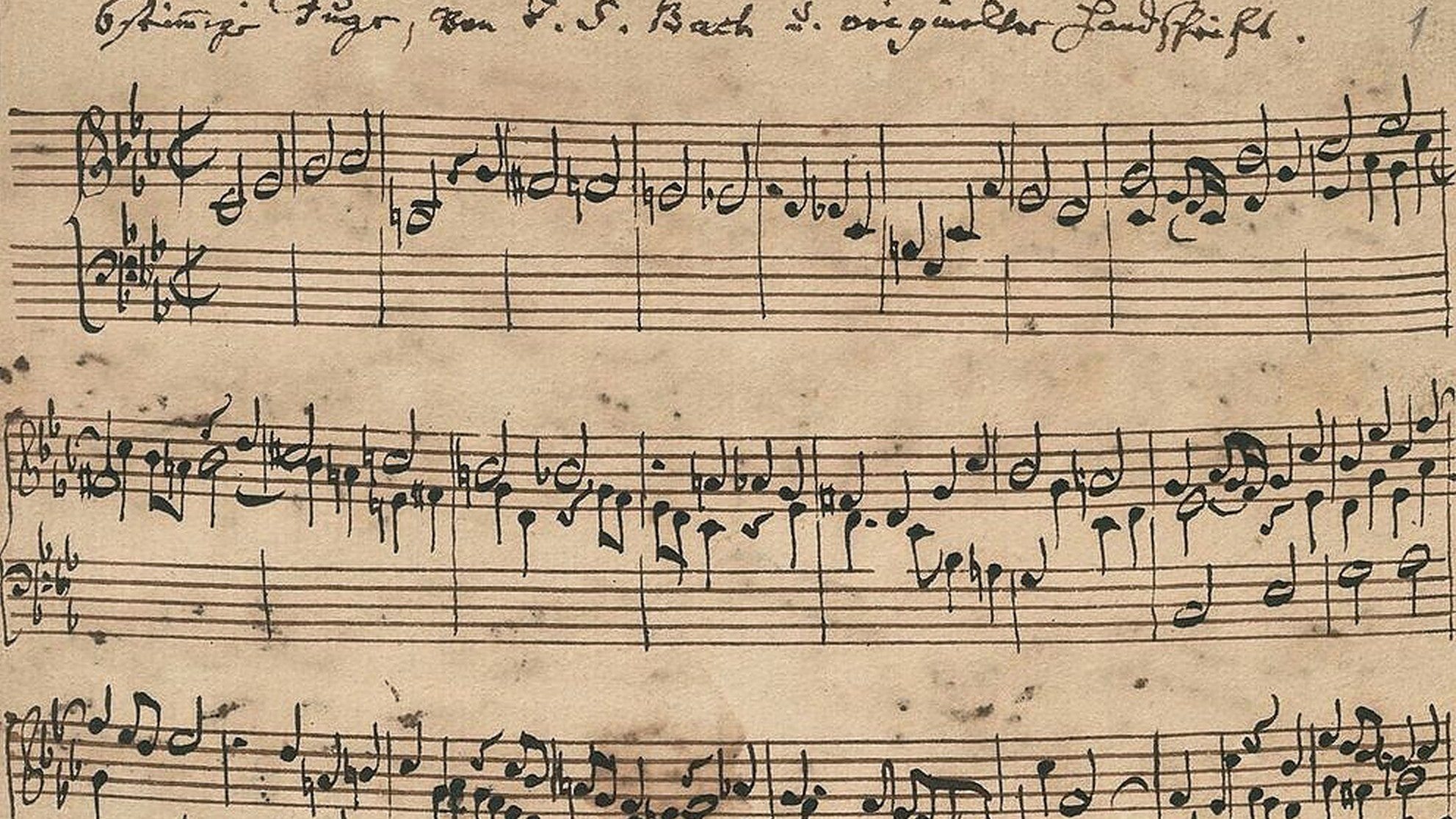

Featured Image: a manuscript copy of Ricercar a 6