…Here a new world is opened up to view, one is raised into a higher ideal region, one senses that the sublime life dreamed of by poets is becoming a reality.

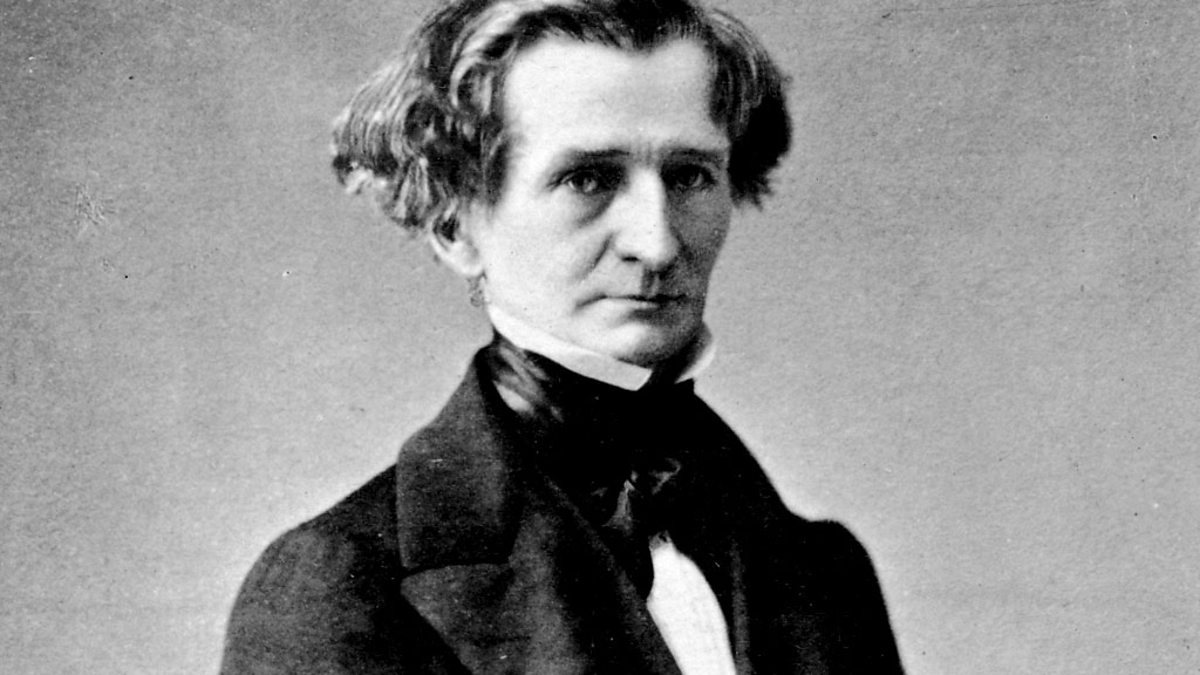

This is how Hector Berlioz described the dramatic potential of a bold new kind of symphonic music- a free-spirited Romanticism born out of the earth-shattering monumentality of Beethoven’s Ninth, which left behind classical balance and order to enter dark, new psychological territory. It’s an aesthetic realized in Berlioz’ Roméo et Juliette, a sprawling, seven-movement-long, genre-defying hybrid which attempts to encapsulate “the sum of passion” of one of Shakespeare’s most powerful plays. I say, “genre-defying” because Roméo et Juliette seems to fall somewhere between opera and symphony. Its adventurous libretto by Émile Deschamps re-shapes the story and includes a surreal line in which Shakespeare is mentioned by name. Dueling choruses represent the Montagues and Capulets. Only in the final movement are they heard together, overcoming their ancient feud. But it’s the orchestra, alone, that depicts the two title characters in the dramatic interior of the work. Language and literal meaning fade into the nocturnal shadows of the Capulet garden and the distant sounds of the ball. We hear the seeds of Wagner, whose operas develop symphonically with long orchestral interludes. Amid all of this formal ambiguity, Berlioz included these ironic lines in the score’s preface:

There will doubtless be no mistake as to the genre of this work. Although voices are frequently employed, it is neither a concert opera nor a cantata but a choral symphony.

Berlioz was 23 when he attended a performance of Shakespeare’s play in 1827. The Irish actress Harriet Smithson (who inspired Berlioz’ infatuation as well as Symphonie Fantastique) played the role of Juliet. In his memoirs, Berlioz describes the impact of the performance:

.. to steep myself in the fiery sun and balmy nights of Italy, to witness the drama of that passion swift as thought, burning as lava, radiantly pure as an angel’s glance, imperious, irresistible, the raging vendettas, the desperate kisses, the frantic strife of love and death, was more than I could bear. By the third act, scarcely able to breathe—it was as though an iron hand had gripped me by the heart—I knew that I was lost. I may add that at the time I did not know a word of English; I could only glimpse Shakespeare darkly through the mists of Letourneur’s translation; the splendour of the poetry which gives a whole new glowing dimension to his glorious works was lost on me. … But the power of the acting, especially that of Juliet herself, the rapid flow of the scenes, the play of expression and voice and gesture, told me more and gave me a far richer awareness of the ideas and passions of the original than the words of my pale and garbled translation could do.

Considering how modern this music sounds, it’s amazing to think that Roméo et Juliette was completed in 1839, just twelve years after Beethoven’s death. While Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony suggests “feelings” of the country, Berlioz fuses music and programatic literary elements in a deeper and more intrinsic way. Individual instruments, with their distinct personas and psychological attributes, combine in innovative new ways which anticipate the deeply psychological music of Mahler. Berlioz writes for an orchestra that is bigger and louder than what came before- augmented with two harps, two tympani, trombones, tuba, triangle, cymbals, and more.

In his 1973 Norton lecture, The Delights & Dangers of Ambiguity (part of The Unanswered Question series), Leonard Bernstein discusses the adventurous, chromatic harmony of Berlioz’ Roméo et Juliette and the way it anticipates the music of Wagner, who attended the premiere. Bernstein demonstrates the way the atmospheric, solitary “love-sick sighs” of the opening of the second movement (Romeo Alone) shamelessly found their way into Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, written twenty-five years later. (Wagner presented Berlioz with a score of Tristan, bearing the inscription, “To the dear and great author of Romeo and Juliet, from the grateful author of Tristan and Isolde.”)

This week I’m experiencing Berlioz’ Roméo et Juliette from the violin section. Glance at the score, or look at one of the individual orchestral parts, and you realize that there’s an endearing touch of insanity in this music. For example, listen to the crazy fugue that develops in this passage. It’s a fugue that seems to behave in all the wrong ways, eventually devolving into a continuous descending line. This is just one example of the free-spirited Romanticism of this remarkable piece.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5MJDd8zEOM

Part I

1. Introduction: Combats (Combat) – Tumulte (Tumult) –Intervention du prince (Intervention of the prince) –Prologue – Strophes – Scherzetto

Part II

2. Roméo seul (Romeo alone) – Tristesse (Sadness) –Bruits lointains de concert et de bal (Distant sounds from the concert and the ball) –Grande fête chez Capulet (Great banquet at the Capulets)

3. Scène d’amour (Love scene) – Nuit serène (Serene night) -Le jardin de Capulet silencieux et déserte (The Capulets’ garden silent and deserted) –Les jeunes Capulets sortant de la fête en chantant des réminiscences de la musique du bal (The young Capulets leaving the banquet singing snatches of music from the ball)

4. Scherzo: La reine Mab, reine des songes (Queen Mab, the queen of dreams – the Queen Mab Scherzo)

Part III

5. Convoi funèbre de Juliette (Funeral cortège for the young Juliet): “Jetez des fleurs pour la vierge expirée” (“Throw flowers for the dead virgin”)

6. Roméo au tombeau des Capulets (Romeo at the tomb of the Capulets) -Invocation: Réveil de Juliette (Juliet awakes) – Joie délirante, désespoir (Delirious joy, despair) –Dernières angoisses et mort des deux amants (Last throes and death of the two lovers)

7. Finale: La foule accourt au cimetière (The crowd rushes to the graveyard) –Des Capulets et des Montagus (Fight between the Capulets and Montagues) –Récitatif et Air du Père Laurence (Friar Lawrence’s recitative and aria) Aria: “Pauvres enfants que je pleure” (“Poor children that I weep for”) –Serment de réconciliation (Oath of reconciliation) Oath: “Jurez donc par l’auguste symbole” (“Swear by the revered symbol”)

Recordings

- Charles Dutoit and the Philadelphia Orchestra, Ruxandra Donose, Gregory Kunde, David Wilson-Johnson, The Philadelphia Singers Chorale: This recording was released in 2010. Listen to an excerpt here. iTunes

- John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique: Listen to an excerpt of this period performance here. iTunes

- Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony: Listen to an excerpt here.

- A rehearsal clip with Leonard Bernstein

Hi Tim , music videos for Berlioz Romeo and Juliet on YouTube are marked as private only. Can you please make it available for me?

Thanks