Last Thursday marked the 60th anniversary of the Broadway opening of Leonard Bernstein’s Candide, a work based on the novella by Voltaire, which falls somewhere between musical theater and operetta. It isn’t often that an overture stops the show, but that’s one of the details Barbara Cook, who played the role of Cunégonde, remembers from the night of December 1, 1956.

I am extremely proud to have been part of the original cast of Leonard Bernstein’s Candide. I have two distinct memories of opening night in New York, December 1, 1956 at the Martin Beck Theatre. First is that the overture stopped the show — people loved it, and to this day it’s one of the most frequently played pieces by symphony orchestras around the world. My second big memory from opening night was Lenny coming backstage to wish me luck. He was just about to leave when he added, “Oh yes, Maria Callas is out front.” I said, “Oh my God, I could have done without knowing that.” Lenny laughed and said “Don’t be ridiculous. She’d kill for your high E-Flats.” The show did great things for my career. More than any other show, Candide has given me a certain musical credibility I wouldn’t have acquired otherwise, especially within the classical music world.

Barbara Cook’s vocal range is on display in her performance of Glitter and Be Gay on the original cast album. It’s one of Candide‘s most enduring excerpts, along with The Best of All Possible Worlds, Oh Happy We, and Make Our Garden Grow. Listen carefully to the melody and the persistently ascending scale lines in this final number, Candide‘s finale, and you’ll hear a not-so-subtle reference to the finale of Stravinsky’s The Firebird.

The Candide Overture is one of music history’s most thrilling, humor-filled romps. It’s a wild ride in which clownish characters practically leap out at us, unleashing one prank after another, right down to the final cadence. The irregular sense of rhythm amid constantly changing meters never allows us to catch our bearing, instead pulling us along, feverishly. (Listen to all the dizzying cross-rhythms in this passage, allowing your ear to focus on each individual part). Sly historical influences were constantly creeping into Bernstein’s music. Towards the end of the Candide Overture, he pays tribute to the long, gradually building crescendo which closes a typical Rossini opera overture. It’s a device so exhilarating that it never gets old.

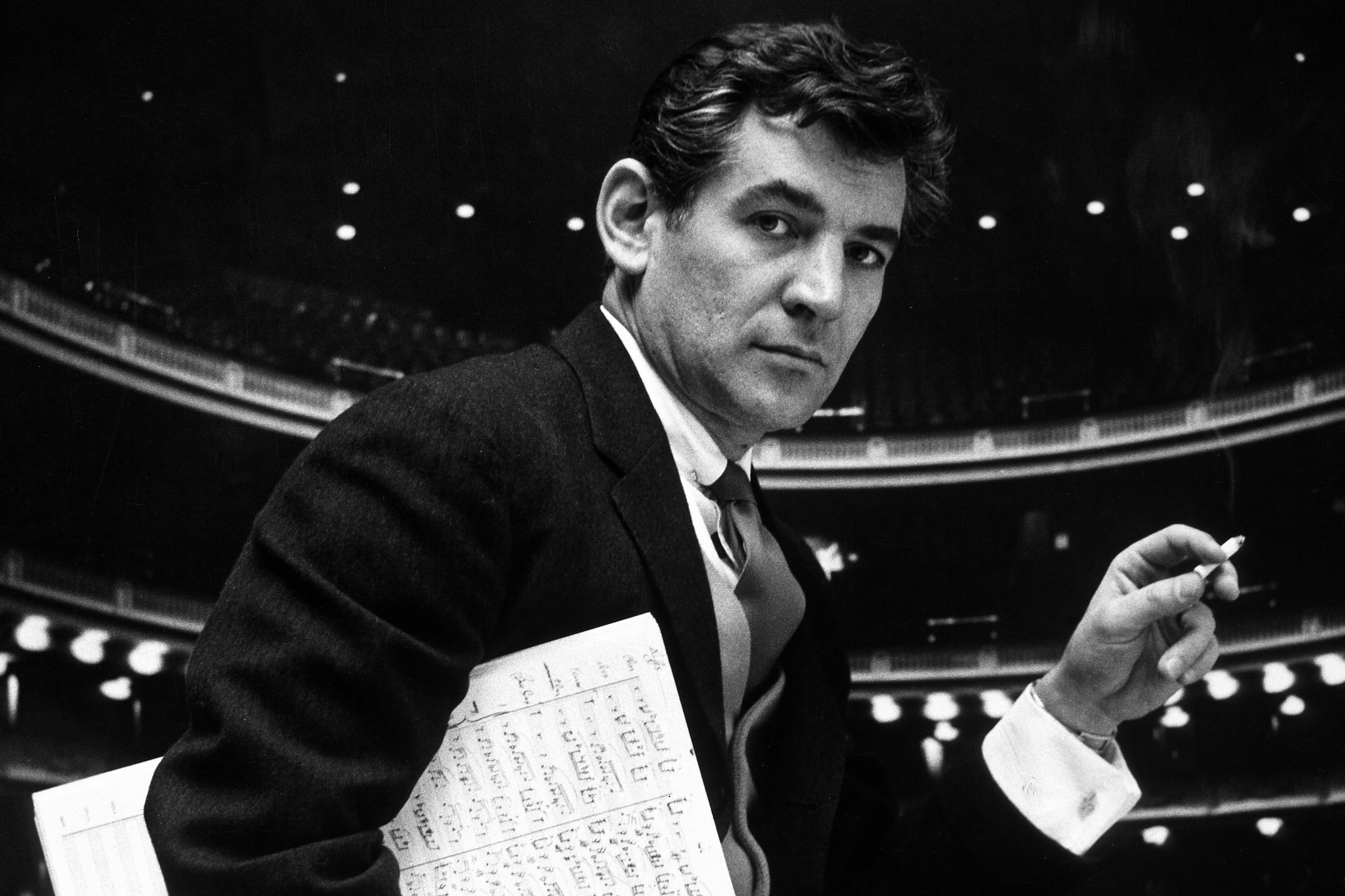

Here is my favorite recording of this piece, from a live concert in the early 1980s. Leonard Bernstein is conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic:

The original production of Candide was a commercial flop, closing after only two months and seventy-three performances. The show has found popularity through a series of revivals which have occasionally moved it into the opera house. Here is a brief description of Bernstein’s revisions of Candide over a series of years.