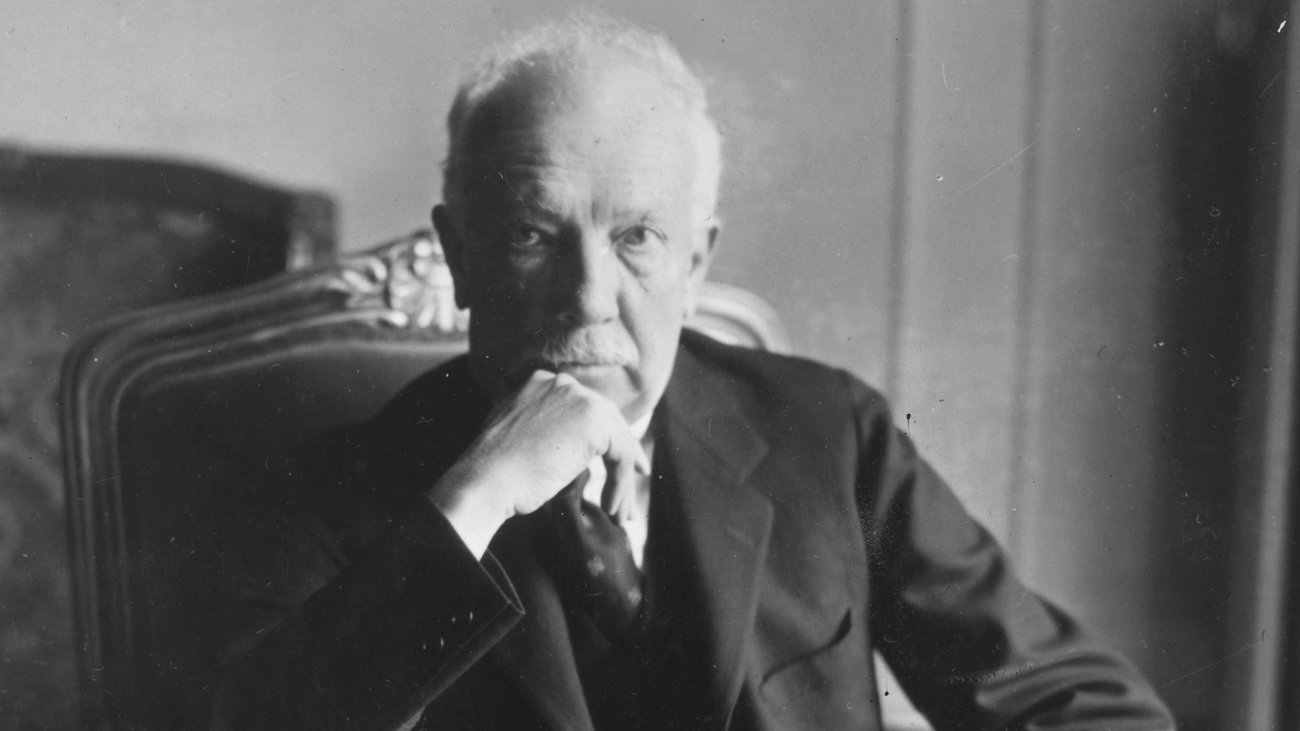

On one level, Richard Strauss’ 1898 tone poem, Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40 (A Hero’s Life), is a musical autobiography. Filled with unflinching bravado, it ventures where few pieces dare to go, casting the composer as hero. In terms of sheer volume and virtuosity, it pushes the orchestra to its limits. (At one point, the violins must tune the lowest string down to G-flat to artificially extend the instrument’s range a half step below the open G string). It centers around E-flat major, the same key as Beethoven’s “Eroica” (“Heroic”) Third Symphony, originally dedicated to Napoleon. (In a letter, Strauss wryly remarked that he found himself “No less interesting than Napoleon.”) While working on the piece in a Bavarian mountain resort in the summer of 1898, the 34-year-old Strauss wrote with less than subtle irony,

Since Beethoven’s “Eroica” is so unpopular with our conductors today and hence rarely performed I am filling the void with a tone poem of substantial length on a similar theme. It is entitled ‘A Hero’s Life,’ and while it has no funeral march, it does have lots of horns, horns being quite the thing to express heroism.

Perhaps it’s no wonder that, following the premiere, one critic savaged the work and its composer as

a monstrous act of egotism, and as revolting a picture of this revolting man as one might ever encounter. He is, then, honest.

Ein Heldenleben is set in six movements which unfold without interruption:

[ordered_list style=”upper-roman”]

- The Hero –Ein Heldenleben’s larger-than-life character is evident from the expansive, swashbuckling opening phrase, which hints at adventure and Nietzschean struggle to come.

- The Hero’s Adversaries -Incessantly prattling woodwinds suggest the small-mindedness of music critics, while the name of the nineteenth-century Viennese music critic Doktor Dehring is outlined in a recurring leitmotif in the two tubas which seems simultaneously ominous and brain-dead. This leitmotif employs parallel fifths- the mother of all voice leading errors.

- The Hero’s Companion -An extended violin solo depicts Strauss’ wife, the singer Pauline de Ahna. He described her as, “very complex, very feminine, a little perverse, a little coquettish, never like herself, at every minute different from how she had been a moment before”.

- The Hero at Battle -This movement begins with the distant sounds of offstage trumpet fanfares. One critic wrote, “The climax of everything that is ugly, cacophonous, blatant and erratic, the most perverse music I ever heard in all my life, is reached in the chapter ‘The Hero’s Battlefield.’ The man who wrote this outrageously hideous noise, no longer deserving of the word music, is either a lunatic, or he is rapidly approaching idiocy.

- The Hero’s Works of Peace -Quotes from Strauss’ earlier tone poems emerge and intermingle in this movement, including Don Quixote, Don Juan, Death and Transfiguration, Macbeth, Also sprach Zarathustra, Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks.

- The Hero’s Retirement from this World and Completion –The opening motive is now heard in the pastoral serenity of the English horn. After so much harmonic turmoil, Ein Heldenleben closes with some incredibly transcendent music. Listen to this noble moment of resolution which reaches ever higher with perhaps music history’s most sensuous use of the major seventh (that expansive surprise at 38:52). A nostalgic duet unfolds between the horn (representing Strauss) and the solo violin (his wife). In the last bars, we hear echoes of the opening of Also sprach Zarathustra in the trumpets. The final chord ranges from the lowest to highest voices of the orchestra.

Now, forget the program…

In my opinion, the best way to experience Ein Heldenleben is to forget about its somewhat trite program. This piece endures because, like all great music, it transcends the literal. Strauss and the imagery of his story fade into the background and a deeper drama begins to unfold. As Wallace Stevens writes in The Snow Man,

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony opened Musikfest Berlin with this performance on August 31, 2013:

Five Recordings

- Strauss: Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40, Pittsburgh Symphony, Manfred Honeck Amazon

- Mariss Jansons and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra iTunes

- Gerard Schwarz and the All-Star Orchestra Arkiv Music

- Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (recorded in 1969)

- Richard Strauss and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra (recorded in 1926)