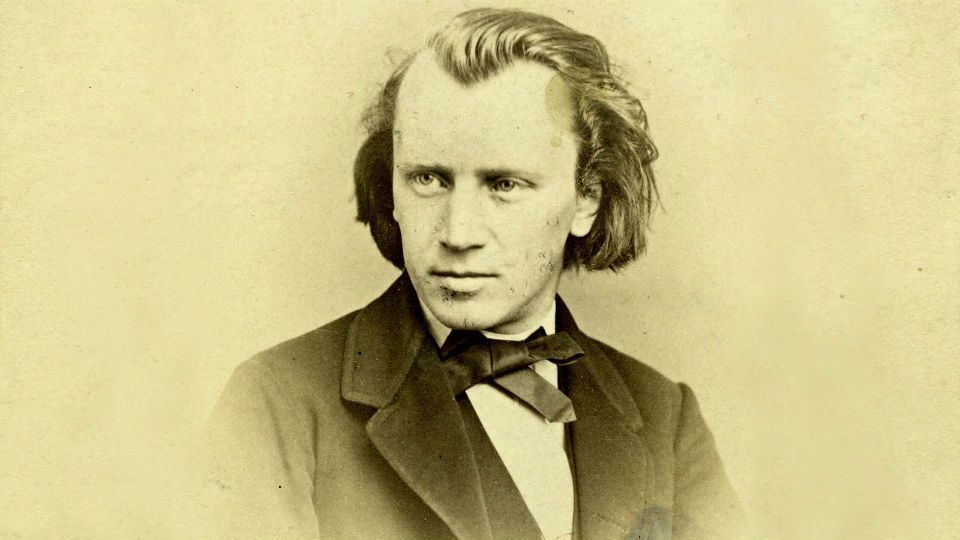

A ferocious, stormy intensity is unleashed in the opening of Johannes Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor. With an ominous inevitability, the expansive opening theme growls, snarls, and lashes its teeth, rising up like some kind of awesome supernatural power. Immediately, we’re drawn into music which is bold and monumental- a kind of symphony with solo piano.

For nearly four years, beginning in 1854, the young Brahms wrestled with the form of this music. It began as a symphony, then turned into a massive sonata for two pianos which Brahms played with Clara Schumann. Finally, it emerged as a piano concerto. But this isn’t the kind of Romantic concerto where a virtuosic solo line is set against a backdrop of orchestral accompaniment. Additionally, we don’t get the sense of “piano versus orchestra.” Instead, we get a work conceived in classical form on a symphonic scale in which piano and orchestra are equals- a vast drama in which an array of voices come alive and converse. In an 1857 letter to the violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms wrote, “I have no judgment about this piece anymore, nor any control over it.”

When the First Concerto was played at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, the audience reacted by hissing. The critic for the Signale described it as,

Three-quarters of an hour of laboring and burrowing, of straining and tugging…Not only must one take in this fermenting mass; he must also swallow a dessert of the harshest dissonances and most unpleasant sounds.

That ominous opening theme, at first filled with harmonic tension and ambiguity, returns throughout the first movement as an inescapable presence. When the piano first enters, we find ourselves in a much different world of quiet, restless melancholy. A second theme is filled with passionate warmth. Listen to the way the piano’s statement is echoed in a distant horn call. As the commentator, Thomas May, notes,

The first movement is of vast proportions and is defined by extremes. It encompasses both the titanic, elemental landscape of the opening theme and the reflective lyricism represented in the theme that the piano first introduces. Somehow Brahms holds these countervailing tendencies in a persuasive balance.

The Adagio awakens amid quiet, serene majesty. Listen to the way the instrumental personas come alive, from the weaving lines of the bassoons and strings to the oboe. As the second movement unfolds, we’re pulled deeper into a world of solemn mystery. It’s a complex mix of lament and warm embrace. At moments, the music seems to hesitate, losing its way, only to find the reassurance of the opening theme. The piano’s elaborate trills open the door to final statements in the orchestral voices and the distant drumbeat of timpani.

The final movement, Rondo. Allegro non troppo, pays homage to the rondo of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. In a rondo form, a principal theme alternates with a series of adventurous episodes. Brahms’ music surges forward with spirited momentum, while taking us on musical side trips which include a string fugue along with sudden modulations. The coda brings this massive, “symphonic” concerto to a transcendent close filled with warmth and gratitude. There are hints of Brahms’ yet unwritten First Symphony. The spirit of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony seems to be lurking just beneath the surface, especially in the jubilant innocence of this quirky, short-lived march.

In a previous Listeners’ Club post, we explored Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto, music which takes on a much different atmosphere, written twenty years later.

Five Great Recordings

- Krystian Zimerman, Sir Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic (This 2006 recording is featured above). iTunes

- Emil Gilels, Eugen Jochum, Berlin Philharmonic iTunes

- Hélène Grimaud, Andris Nelsons, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks

- Nicholas Angelich, Paavo Järvi, Orchestre de Paris

- Leon Fleisher, George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra

I completely agree with your selection of suggested recordings (in fact, I’m listening to the Zimerman CD now — I had forgotten how electrifying the partnership with Rattle and the Berliners was!) May I also add both recordings by Stephen Hough, the one on Warner and the recent one on Hyperion. The former can be sampled on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/album/502kv6NiOwZK7dLDEbkbbc?si=4kQ-jsL1TRGh5E4vWlSxVQ