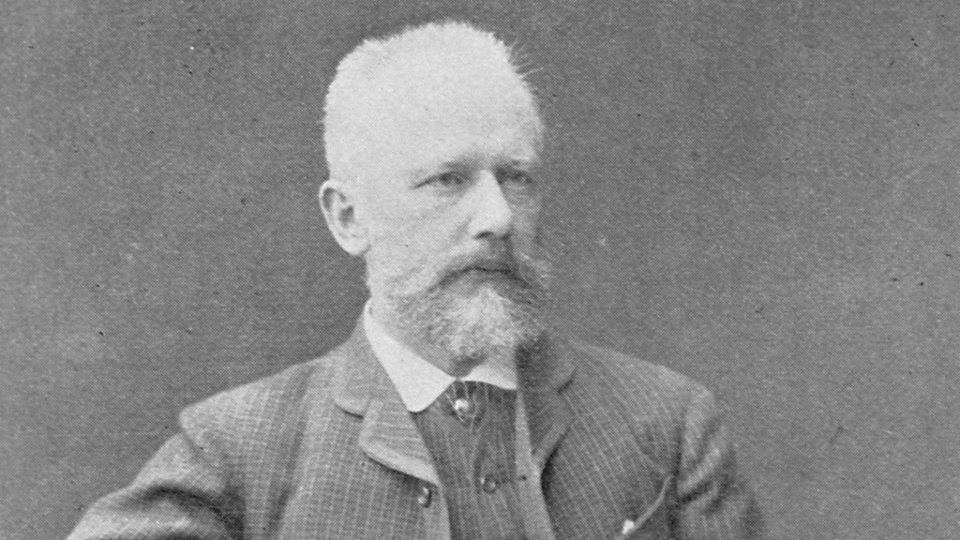

A romantic myth has grown up around Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony. The composer’s final work has been cast as a kind of despairing musical suicide note.

It is true that Tchaikovsky died just over a week after conducting the Symphony’s premiere on October 28, 1893, probably as a result of drinking cholera-infected water. But while Tchaikovsky’s personal battles and bouts with depression have been well-documented, he completed the Sixth Symphony on an emotional upswing. Tchaikovsky told his younger brother, Anatoly, “I am very proud of my symphony, and think that it’s my best composition.” In letters to friends he wrote, “I think it will be successful; it is rare for me to write anything with such love and enthrallment,” and “I can honestly say that never in my life have I been so pleased with myself, so proud, or felt so fortunate to have created something as good as this.” Even the Symphony’s subtitle, “Pathétique,” which was suggested by the composer’s younger brother, Modeste, is deceptive. Its Russian translation is closer to “passionate” or “emotional” than “sad.”

Yet, in the “Pathétique” Symphony, a dark, lamenting, and sometimes terrifying drama unfolds. Its journey ends in resignation and ultimate death rather than transcendence. It follows a much different course than perhaps any symphony which came before. Gone is the journey towards transcendence we hear in Tchaikovsky’s preceding symphonies, in the triumphantly-concluding symphonies of Beethoven, or the Schumann Second Symphony we explored last week. Instead, the “Pathétique” Symphony delivers a haunting farewell. It anticipates another “farewell” symphony which fades into silence- Mahler’s Ninth, as well as similar disquieting symphonic conclusions by Sibelius (the Fourth and Sixth Symphonies).

The first movement (Adagio – Allegro non troppo) begins in the lowest, cloudiest depths of the orchestra with primal open fifths in the divided double basses and a rising melody in the bassoon. Every time I hear this opening melody, I’m struck by its shadowy resemblance to the serene horn solo in the second movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Descending scales are a recurring motive in this Symphony- they occur at the end of each movement. Early in this opening introduction, as if to negate the aspirations of the tentatively-rising woodwind lines, a bitter descending line in the strings sinks back into the gloom. This unfolds into the exposition’s first theme, which features an interplay between rising and falling scales. We hear the grace, elegance, and buoyancy of Mozart- a composer whom Tchaikovsky greatly admired- as well as Tchaikovsky’s ballet music. Immediately in this exposition, there is an explosion of counterpoint, conversations between groups of instruments, and restless and relentless motivic development. The second theme, again built on falling scales, begins with hushed sensuosity in the muted strings before soaring passionately. Even at its most climactic moments it is tinged with sadness. Notice the way this theme comes out of, and returns to, silence.

The ferocious development section begins with a sudden eruption which some listeners have compared to the opening of the Infernal Dance of Stravinsky’s The Firebird. During a Richmond Symphony rehearsal earlier in the week in which I heard only the wind and brass lines in this passage, I was struck by the absence of any tonal center. Heard alone, these voices could easily be mistaken for a twentieth century twelve tone composition. A few moments later, notice the way our sense of the underlying pulse is broken down into dizzying rhythmic ambiguity, something we hear throughout Tchaikovsky’s ballet music. The exposition’s graceful opening theme now becomes a deranged game of imitation between the strings and winds. What follows may be the most terrifying and awe-inspiring moment in all of Tchaikovsky’s musical output. Amid growing layers of sound building above the timpani’s rumbling pedal tone, a vast, inescapable Power rises up before us. A fateful statement rises in the trombones, with their supernatural connotations. Earlier in the development section, the trombones intone a brief but solemn quote from this section of the Russian Orthodox Requiem Mass.

The first movement ends with a resigned march into the sunset. Listen to the way the chorale voices meet the unwavering descending pizzicato scales at just the moment that causes a suspension of bittersweet dissonance. In the last seconds, listen closely for those final timpani beats which fade off into the distance.

The second movement (Allegro con grazia) is a graceful but strangely limping waltz set in the highly irregular meter of 5/4 time. Listening to the underlying bass pizzicato, its hard to imagine music which keeps us more delightfully off balance. This is unchoreographed ballet music, with its magical and visceral sense of motion. In the second theme, a descending scale fragment emerges once again and the music takes an ominous turn. Notice the way the original theme enters the woodwind lines as a seeming embellishment. This “embellishment” takes over and becomes a conversation between instruments which then, sneakily, melts back into the original theme.

“Exhilarating” is the best word to describe the march-like third movement (Allegro molto vivace). It begins with an array of sparkling colors and a flurry of moving lines. Then, a spirited march theme emerges. Throughout this Scherzo there is an almost frightening sense of continuously-building tension. All of this pent-up energy is released in an explosion of triumph and euphoria. The end of this movement rides so high that it almost becomes a “false” finale. “Why couldn’t Tchaikovsky have ended here?” we ask.

The final movement (Finale: Adagio lamentoso) feels even more heart-wrenching because of what precedes it. The opening theme is a cry of anguish, yet there is also an underlying sense of nobility and acceptance. If you look at the score, you won’t find this melody in any one instrumental line. Instead, it is divided in alternating notes between the first and second violins. In the days when violin sections were seated facing each other this must have produced a fascinating “surround sound” effect that may be lost today. The dissonant tension of the suspensions in the coda of the first movement return more expansively here. We’re plunged back into the murky world of the low strings and bassoon which opened the Symphony. The second theme is a majestic statement built on the descending scale motive. It grows, reaching higher toward an unattainable climax. The fateful voice of the trombones emerges in a canonic dialogue with the strings.

This is music which tries desperately to find a way forward to ultimate resolution but fails, repeatedly. Instead, we are swept into the stormy ferocity of this passage, with its snarling, stopped horns, followed by a sombre trombone and tuba chorale which feels like a musical prayer of last rites. The final descending scales sink into the depths of the orchestra, where the Symphony began. Instruments drop out successively as the music moves below their range. In a particularly poignant example, the violins conclude with B- A- G and are left hanging, unable to finish the line to F-sharp. The final bars die away, finding resolution only in the silence which follows the last note.

Five Great Recordings

- Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 In B Minor, “Pathétique,” Op. 74, Charles Dutoit, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal Amazon

- Evgeny Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra

- Michail Pletnev and the Russian National Orchestra

- Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic

- Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic

Modest Tchaikovsky was the YOUNGER brother of Pyotr Tchaikovsky by almost exactly ten years. Modest was also a twin of Anatoly Tchaikovsky.

Thank you very much for this insightful, well-written analysis of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony. Tchaikovsky is one of my very favorite composers, whether it is a symphony, opera or ballet!