On Monday, we explored five monumental scherzos from nineteenth and twentieth century symphonies. These ferocious works leave behind the original lighthearted concept of the “scherzo,” which means “joke” in Italian. The dynamic, sometimes terrifying, drama unleashed in this music is anything but a joke.

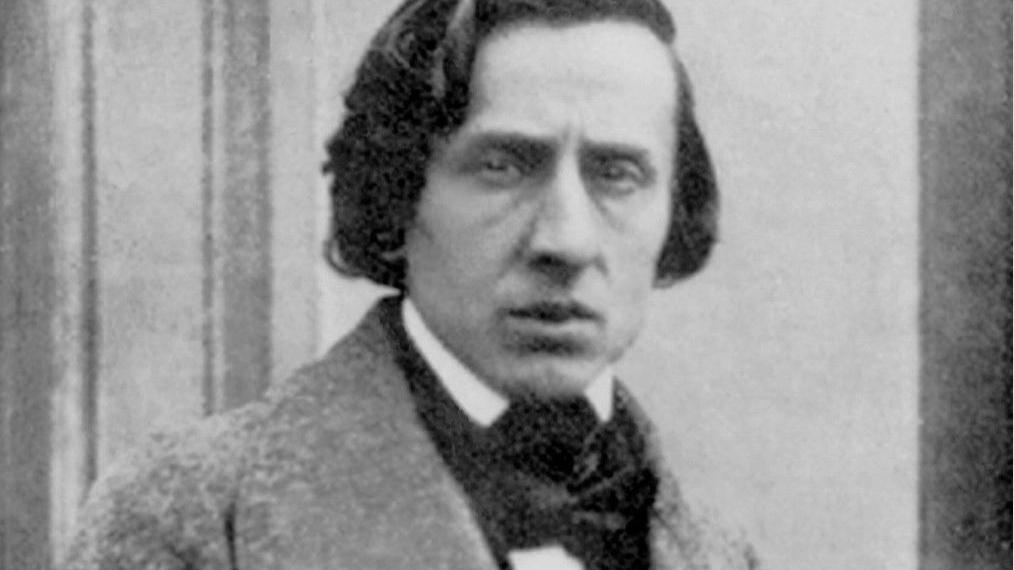

Fryderyk Chopin’s four Scherzos for solo piano are similarly definition-shattering. They are filled with moments of haunting mystery, turbulence, soaring Romantic fervor, and intense drama. In his review of Scherzo No. 1 in B minor, Robert Schumann commented on the seeming contradiction between this dark, fiery music and its title, asking,

How is ‘gravity’ to clothe itself if ‘jest’ goes about in dark veils?

Scherzo No. 1 in B minor, Op. 20

The B minor Scherzo begins with a terrifying cry of anguish. This jolting, tension-filled opening chord comes out of nowhere, unleashing a fiery torrent of virtuosic sparks which fly up and down the keyboard. Just as suddenly, this dissolves into a quietly brooding dialogue between treble and bass. The middle section (molto più lento) quotes the old Polish Christmas song, Lulajże Jezuniu. (As Chopin composed this music in Vienna in 1831, the November Uprising against the Russian Empire was raging in his native Poland). The dreamy nostalgia of this middle section is rudely interrupted by a return of the ominous opening chord. But listen to the way the quiet music lingers, as if unaffected as the two “worlds” clash.

Here is Sviatoslav Richter’s live 1977 recording:

Scherzo No. 2 of B-flat minor, Op. 31

The second Scherzo opens with a ghostly “bump in the night.” This opening “question” is answered by a bold, heroic statement. Harmonically, the piece begins in B-flat minor, but finds resolution in D-flat major. Even without paying attention to the conflict between these two keys, you can feel the underlying sense of restlessness right down to the final bars of the coda. For Schumann, this mercurial Scherzo brought to mind this line from a Byron poem:

so overflowing with tenderness, boldness, love and contempt

Here is a performance by Krystian Zimerman:

Scherzo No. 3 in C-sharp minor, Op. 39

The third Scherzo begins in a dense fog of rhythmic and harmonic ambiguity. There is something almost demonic about the opening statement with its tonality-defying chromaticism. Gradually, the music finds its tonal center while searching for a way forward. Perhaps the insecurity of this opening makes the noble D-flat major chorale melody of the Meno mosso all the more powerful, with its cascading arpeggios. You can hear intimations of the music of Wagner throughout this piece, completed in 1839 (four years before the premiere of The Flying Dutchman). For example, listen to the extraordinary extended passage beginning around 3:12. Or listen to the expectation-building delay of the resolution around 5:25.

Here is Rafael Orozco’s 1975 recording:

Scherzo No. 4 in E Major, Op. 54

The sun comes out in Chopin’s final Scherzo, completed in 1842. The spirited opening music is contrasted with a beautifully expansive, operatic cantilena melody in the middle section. This is music filled with joyful, almost childlike splashes of color. Just before the final resolution, listen to the way the main motive moves into the shimmering highest register of the piano.

Here is a 2010 performance by Daniil Trifonov:

Five Great Recordings

- Chopin: Four Scherzi and 13 Preludes Sviatoslav Richter Amazon

- Chopin: Krystian Zimerman plays Chopin and Schubert Amazon

- Chopin: The Four Scherzos, The Four Ballades, Rafael Orozco Amazon

- Chopin: Mazurkas Op.56, Nocturne in B Major, Scherzo in E Major, Piano Concerto in E Minor Op. 11, Daniil Trifonov Amazon

- Chopin Scherzi Nos. 1-4, Arthur Rubinstein Amazon