In his 1998 book, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, the late literary critic Harold Bloom made the bold argument that Shakespeare “went beyond all precedents (even Chaucer) and invented the human as we continue to know it.” According to Bloom, Shakespeare’s complex and multifaceted characters “take human nature to some of its limits, without violating those limits” and open up “new modes of consciousness.” The drama that unfolds in the lines of Shakespeare is so profound and revelatory that “no one yet has managed to be post-Shakespearean.” The work is so strong that we have no sense of the author’s individual voice or point of view, only the sense of a higher power at work.

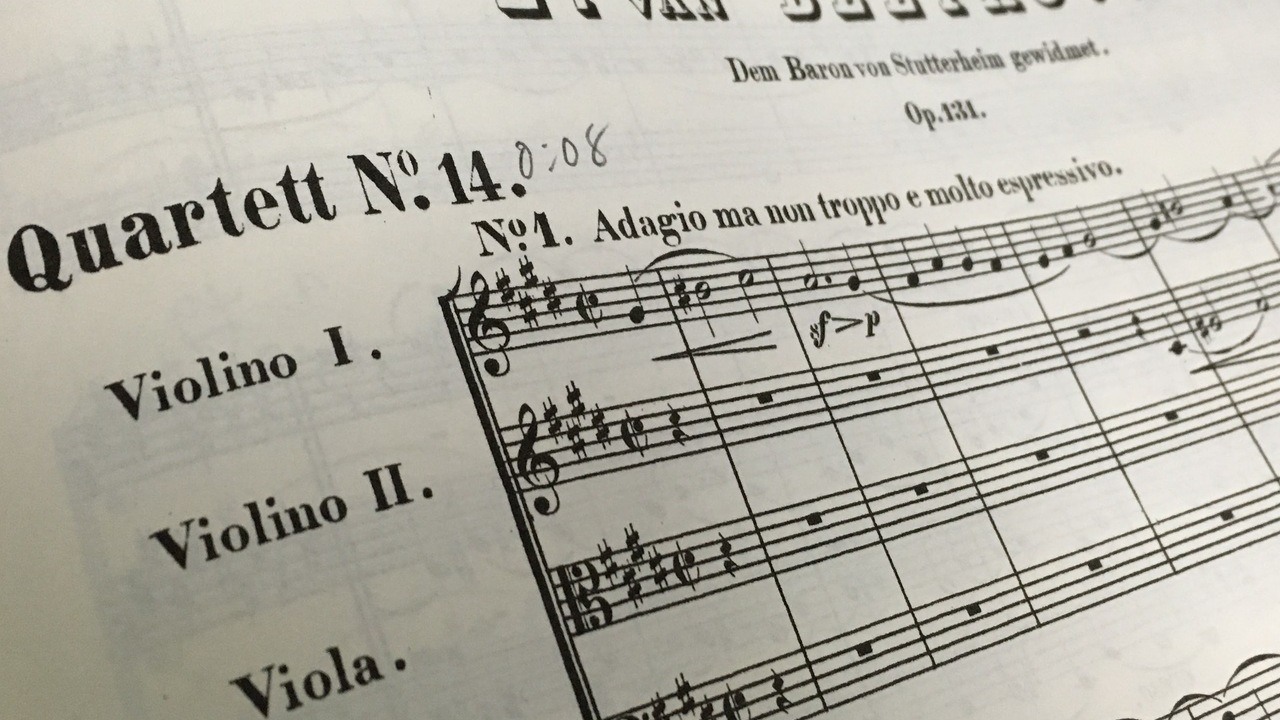

Listening to Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131, we get a similar sense of transcendence and lack of precedent. Written in 1826, a year before the composer’s death, this work is one of Beethoven’s mysterious and revelatory late string quartets—music that was considered so strange and radical at the time that it prompted one perplexed musician to say, “we know there is something there, but we do not know what it is.”

This is music which moves into a new dimension. I can’t think of any other music which so profoundly negates all sense of style and previous influence. It leaves behind everything which came before, including Beethoven’s earlier works. Standing outside of any time period, it feels eternally “contemporary.” It was Beethoven’s favorite Quartet. The composer remarked to a friend, “a new manner of part-writing and, thank God, less lack of imagination than before.” These four conversing voices come to life with a unique sense of freedom and divine inevitability. Although this music was not heard publicly until 1835, Schubert requested a private performance five days before his death in 1828. After hearing the Quartet he remarked, “After this, what is left for us to write?”

Set in seven movements which flow together in a continuous musical stream, the Op. 131 Quartet turns the traditional string quartet form on its head. It opens with a gradually unfolding fugue (Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo) which Wagner described as “the most melancholy sentiment ever expressed in music.” The writer J.W.N Sullivan called this “the most superhuman piece of music that Beethoven has ever written.” It occupies the same mystical territory as parts of Beethoven’s Missa solemnis. Musical phrases break down and overlap in a way which keeps pulling our attention to the moment. Some commentators hear this first movement as a vast exposition section out of which the rest of the Quartet develops.

The second movement (Allegro molto vivace) begins abruptly, stepping from C-sharp up a half step to D and bringing a euphoric joy and gratitude. The third movement (Allegro moderato-Adagio) lasts for only eleven bars. Listen to the way the instruments converse in this wordless operatic recitative.

The fourth movement (Andante ma non troppo e molto cantabile) occupies the expressive heart of the Quartet. It is a series of seven far-reaching variations which grow out of a sublimely simple melody. At moments, we hear foreshadowings of Mahler adagios to come. Beethoven was a composer who worked out ideas in extensive sketches, as if struggling to wrap his arms around such monumental ideas. In his book, Beethoven and the Creative Process, musicologist Barry Cooper points out that “This variation movement was so extensively altered that one or more complete leaves had to be removed from the score in every variation except for one, while what began as the final score in the finale gradually degenerated into the status of a sketch.”

The fifth movement (Presto) is a wildly boisterous scherzo. This is that mix of ferocity and humor we often hear throughout Beethoven’s music. At one point, all four instruments intone a ghostly pianissimo sul ponticello (a raspy sound created by playing close to the bridge). This sound of the twentieth century came into the ear of a composer who had been completely deaf since 1816.

The Presto fades into the solemn and mysterious sixth movement (Adagio quasi un poco andante), which serves as an introduction to the final movement (Allegro). The finale opens with a startling ferocity that grows more intense as the music develops. A quote of the opening movement’s fugue theme brings us full circle. Yet this final movement is filled with unpredictable turns and ambiguity. When we reach the final cadence in C-sharp major, it feels strangely inconclusive and open-ended. It’s as if the sublime drama which unfolds throughout the Op. 131 Quartet cannot be fully contained or resolved, and its voices continue into eternity.

Here is the Takács Quartet’s landmark 2003 recording:

Five Great Recordings

- Beethoven: String Quartet No. 14 I C-sharp minor, Op. 131, Takács Quartet Amazon

- Jasper String Quartet

- Quartetto Italiano

- Alban Berg Quartet (live concert recording)

- Budapest String Quartet (1961 recording)

Dear Timothy,

I love your programme notes on Beethoven 131, I’m playing this soon in a music society’s series, would you mind if I quoted you in the programme?

Thank you,

Joana

Hi Joana,

Feel free to quote any part of these with attribution. Best wishes for your upcoming performance!

Many thanks, Timothy!

All the best,

Joana