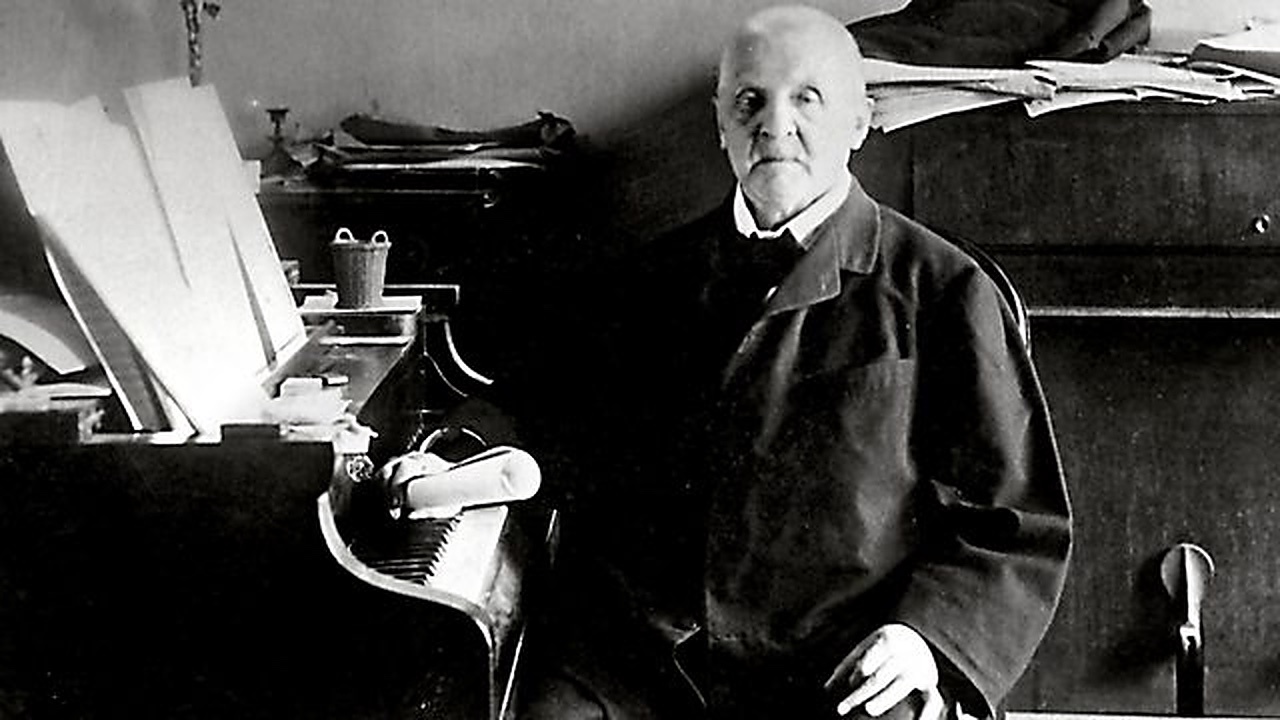

The premiere of Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3 in D minor stands as one of music history’s most infamous disasters.

The performance took place in Vienna on December 16, 1877. It was to have been conducted by Johann Herbeck, an Austrian maestro who had led the posthumous premiere of Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony in 1865. But Herbeck died suddenly, and Bruckner—an accomplished organist and choral director but an inexperienced orchestral conductor—decided to take his place on the podium. The musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic treated the score with disrespect and heckled Bruckner throughout the rehearsals. The performance was met with laughter and catcalls from the audience, many of whom walked out in between movements. By the end, only around 25 dedicated fans remained to offer support to the inconsolable composer. Among them was the young Gustav Mahler.

Beyond Bruckner’s incompetence as a conductor, a number of factors led to the disaster. The Vienna Philharmonic had so disliked Bruckner’s Second Symphony that they turned down a dedication from the composer. The original version of the Third Symphony had been rejected by the orchestra in 1873. Additionally, in Vienna’s politically charged musical environment, the Third Symphony’s occasional quotes of Wagner’s music inspired ridicule. Most importantly, Bruckner’s music offered new and bewildering revelations.

Bruckner’s Third Symphony attempts to enter the mysterious, cosmic world of Beethoven’s Ninth—intimidating territory almost every previous nineteenth century composer avoided. In a way similar to Schubert’s final two symphonies, it develops with a circular inevitability. Its structure is like a vast, majestic cathedral. Rather than spinning towards a far-off goal, this music forces us to stay rooted in the moment. We must approach Bruckner as we might the music of Palestrina, Alan Hovhaness, or Arvo Pärt. (This string passage from the Third Symphony’s first movement could be mistaken for one of Pärt’s meditative, repeating lines). With each of his symphonies, Bruckner ventured into the same mystical territory, as if searching for some kind of ultimate truth. The Third Symphony, completed when Bruckner was nearly 50 years old, begins this journey. It’s the first of the nine symphonies to represent Bruckner’s full and mature mastery of the form.

As with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the first movement begins with hushed, mysterious open fifths. A distant trumpet call announces the principal motif over a ghostly rhythmic motor. Filled with shivering anxiety, these opening bars seem to emerge out of silence. The shadowy strands build into a frightening, cacophonous crescendo. As the music unfolds, the orchestra seems to transform into a mighty pipe organ, with single thematic lines occurring in expansive octaves. Silence becomes as important as sound. In a way similar to Schubert, the orchestra is divided into sonic blocks of sound, creating string, wind and brass “choirs.” Slow down, close your eyes, and listen carefully to this majestic symphonic edifice, filled with heroic statements, haunting mystery, and reverence.

The second movement begins with a noble chorale. Momentary echos of the chromatic lines of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde blend with music which speaks with an almost Baroque clarity. It is simultaneously expansive and intimate. Vast sonic vistas, filled with shimmering colors, open in front of us. Gradually building in intensity and then halting in silence, we get the sense that we are entering into an intimate musical prayer. Every moment seems to be searching and arriving at the same time. The final bars emerge suddenly out of hushed tremolo, bringing the ultimate sense of celestial repose.

The Scherzo third movement begins with a single, snaking melodic strand. “Scherzo” translates as “joke,” but here the humor has a dark, ominous tinge. An initial ghostly whisper grows into an awesome titanic power. We are swept into a terrifying demonic dance. Gentler music lulls us into complacency, but soon the exhilarating ferocity returns. The movement’s Trio section takes us to a completely different world. It feels like a bucolic Austrian peasant dance, with occasional hints of birdsongs.

The opening of the Finale springs to life with the same explosive energy which began the Scherzo. A four note ascending chromatic line begins as a tiny cell and then explodes throughout the orchestra. Open fifths recall the mystery-shrouded beginning of the first movement. The main theme, stated by the brass choir, mirrors the trumpet’s opening theme rhythmically. The tension dissipates with the second theme, a return to the kind of rustic dance we heard in the Scherzo’s Trio section. This theme has been described as the meeting of two disparate elements, a polka (in the strings) and a chorale (in the brass and winds). Bruckner’s biographer, August Göllerich, recounts a conversation he claims to have had with the composer during a walk in Vienna. Joyful dance music drifted out of the windows of one of the houses, while the deceased body of the architect Friedrich Freiherr von Schmidt lay in the house across the street. “Listen!” said Bruckner. “In that house there’s dancing, while over there the Master lies in his coffin. That’s life. That’s what I wanted to show in my Third Symphony. The polka represents the fun and joy in the world, the chorale its sadness and pain.”

In the Symphony’s final moments, the orchestra is transformed into a mighty, cosmic pipe organ. The strings “shadow” the brass in a way which seems to evoke the multiple second-long acoustical delay in a vast cathedral. There is a brief memory of the first movement’s second theme. (The Symphony’s original version “bids farewell” to themes from each movement in a way similar to Beethoven’s Ninth). In the final bars, a blazing fanfare announces the trumpets’ triumphant statement of the first movement’s opening theme, now transformed into heroic D major. As I listen to this thrilling apotheosis, punctuated by the Chicago Symphony brass section in the 1993 recording below, I can’t help but think that Bruckner’s Third Symphony has been vindicated by time.

I. Gemäßigt, mehr bewegt, misterioso (Moderate, more animated, mysterious):

II. Adagio: Bewegt, quasi Andante (With motion, as if Andante):

III. Scherzo: Ziemlich schnell (Fairly fast) (also Sehr schnell):

IV. Finale: Allegro (also Ziemlich schnell):

The Original 1873 Version

There are at least six versions of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3. The recording above, featuring Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, is the 1877 version, edited by Leopold Nowak. In this version, most of the Wagner quotations were removed and a coda was added to the Scherzo. (In the autograph manuscript the coda was marked, “not to be printed.”) It was this version that Mahler used to create a transcription for two pianos, and there is some evidence that Bruckner may have considered it “definitive.” Yet, controversy remains regarding the preferred version of this symphony.

In some ways, the original version, not published until 1977, is like a sketch of the later music. Yet, it is also the most shocking and audacious. In the opening of the first movement, the sustained dominant crescendo takes on extraordinary power. At moments, it’s like listening to a completely different piece. Here is a recording of the original 1873 version, performed by Eliahu Inbal and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony:

Five Great Recordings

- Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1877 version) Amazon

- Eliahu Inbal and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony (original 1873 version) Amazon

- Roger Norrington and the Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR (original 1873 version)

- Eugen Jochum and the Staatskapelle Dresden (1889 version)

- Günter Wand and the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester (live recording)

Lovely work, as always, Timothy! Thanks!

Just heard a rockin’ performance by Scott Yoo and the Featival Mozaic orchestra (SLO CA) so I turned to other sources of insight- your comments were very complementary. I must confess I was dubious going in that this was the right piece for the Festival finale as the soloist was Helene Grimaux performing Schumann concert- mesmerising, enchanting, exciting. Yoo sold the 3rd!

I just love this symphony, the 1877 version, which has a power beyond the sound. I love it as much as the eighth and can’t understand why Simpson and others are so critical of it. Bruckner deliberately goes sparingly on that strong opening theme which keeps its overwhelming strength as it reemerges in the finale. No to mention that startling climax of the slow movement which has a wonderful effect and could not be imitated.

Szell Cleveland

Wonderfully paced