Richard Strauss’ tone poem, Tod und Verklärung, Op. 24 (“Death and Transfiguration”) grapples with the most fundamental questions of the human experience. What is the nature of life? What lies on the other side of death? What happens in that serene moment of ultimate repose as the soul melts into “the infinite reaches of heaven?”

Ironically, this cosmic musical drama, concerned with the twilight of life, was completed in 1889 by the 25-year-old Strauss. Already celebrated for the blazing tone poem Don Juan, the young composer spent the summer of 1888 working as a répétiteur (a vocal coach) for a Bayreuth Festival production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. As with Wagner’s Tristan, Strauss’ tone poem takes a cosmic journey in which intense struggle finds release in a final, transfiguring harmonic resolution. For Strauss, the tone poem becomes a kind of opera without words. It’s music filled with bursts of ferocious struggle, longing, lament, wistful nostalgia, mystery, and quiet acceptance. On one level, it can be experienced as a shifting kaleidoscope of vivid color, or an intricate, dizzying contrapuntal dialogue. Its motifs undergo the thematic transformation developed by Franz Liszt. For an extensive analysis of these motifs, I recommend Richard Atkinson’s recently released deconstruction.

Strauss described the dramatic outline of Death and Transfiguration in an 1894 letter to his friend Friedrich von Hausegger:

It was six years ago when the idea came to me to write a tone poem describing the last hours of a man who had striven for the highest ideals. The sick man lies in bed breathing heavily and irregularly in his sleep. Friendly dreams bring a smile to the sufferer; his sleep grows lighter; he awakens. Fearful pains once more begin to torture him, fever shakes his body. When the attack is over and the pain recedes, he recalls his past life; his childhood passes before his eyes; his youth with its striving and passions and then, while the pains return, there appears to him the goal of his life’s journey, the idea, the ideal which he attempted to embody, but which he was unable to perfect because such perfection could be achieved by no man. The fatal hour arrives. The soul leaves his body, to discover in the eternal cosmos the magnificent realization of the ideal that could not be fulfilled here below.

Following the premiere, Strauss asked his friend, the poet Alexander von Ritter, to write a descriptive program for the work, which unfolds in four uninterrupted sections. You can read Ritter’s interpretation of the music below. But if you are new to this music, I recommend that you first listen without regard to a literal program. As with opera, this is music with overtly dramatic origins. Yet, its real magic and enduring quality lie beyond the literal in the world of pure music.

Death and Transfiguration begins with a weak, failing rhythmic “heartbeat” which gives us a visceral sense of the passage of time. As the piece develops, you will hear this “heartbeat” motif return with haunting persistence. It lurks in the shadows in the timpani, leaps out at us as a taunting interruption in the trombones (11:38), and grows into a terrifying, titanic power. Soft “sighs” in the strings alternate with conversing woodwinds and the celestial tones of two harps—a prominent voice throughout the piece. Following a ferocious battle in which motifs representing “life” and “death” become interlocked in struggle, we hear the first fragments of the famous “transfiguration” motif in the brass (7:49). John Williams paid homage to this motif with the “love theme” of his score for the 1978 film, Superman. The theme’s upward sweep can be heard prominently during the film’s shimmering “Flying Sequence.” You will hear the similarity immediately as Strauss’ theme, now appearing in its full glory, emerges into the sunshine a few minutes later (13:03).

Around the work’s structural Golden ratio, the music seems to evaporate into the ether with an upward-floating chromatic scale. We enter the hypnotic dreamscape of the final section. A stark funeral procession grows out of primal elements—a “C” in the depths of the orchestra which seems to anticipate the opening of Strauss’ later tone poem, Also Sprach Zarathustra, followed by open fifths and the quiet tolling of a gong. Gradually, the “transfiguration” motif takes shape. As the music drifts ever higher towards its celestial goal, the motif takes the form of an angelic presence, simultaneously comforting and lamenting. In the afterglow of the climax, the final bars give us a glimpse of eternal mystery before the serene, final resolution in C major—the purest of all keys.

The “transfiguration” motif returns as a passing ghost in Strauss’ Four Last Songs, written 61 years later. In the fourth song, Im Abendrot (“At Sunset”) it accompanies the soprano’s final line, “Ist dies etwa der Tod?” (“Could this then be death?”). In 1949, as the composer lay on his deathbed, he remarked to his daughter-in-law, “It’s a funny thing Alice, dying is just the way I composed it in Tod und Verklärung.”

Alexander von Ritter’s program for Death and Transfiguration, written following the work’s June, 1890 premiere:

I. (Largo) In a dark, shabby room, a man lies dying. The silence is disturbed only by the ticking of a clock – or is it the beating of the man’s heart? A melancholy smile appears on the invalid’s face. Is he dreaming of his happy childhood? II. (Allegro molto agitato) A furious struggle between life and death, at whose climax we hear, briefly, the theme of Transfiguration that will dominate the final portion of the work. The struggle is unresolved, and silence returns. III. (Meno mosso ma sempre alla breve) He sees his life again, the happy times, the ideals striven for as a young man. But the hammer-blow of death rings out. His eyes are covered with eternal night. IV. (Moderato) The heavens open to show him what the world denied him, Redemption, Transfiguration – the Transfiguration theme first played pianissimo by the full orchestra, its flowering enriched by the celestial arpeggios of two harps. The theme climbs ever higher, dazzlingly, into the empyrean.

Five Great Recordings

- Strauss: Tod und Verklärung, Op. 24, David Zinman, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich Amazon

- Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (1983 recording)

- James Levine and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra (1995 recording)

- George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra (1959 recording)

- Mariss Jansons and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (2014)

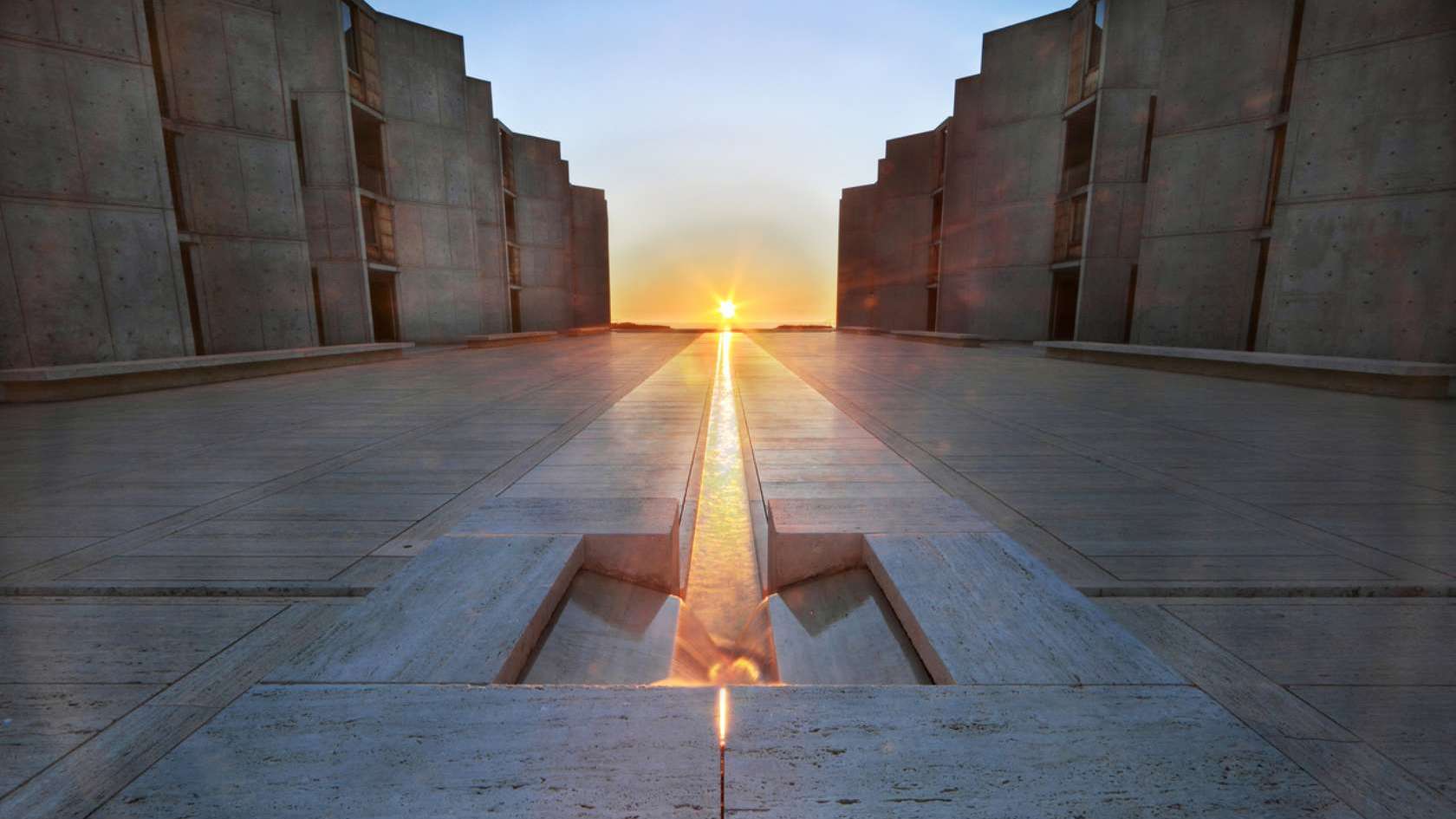

Featured Image: The sun sets into the Pacific Ocean at California’s Salk Institute, designed by Louis Kahn.

Great insight into a great piece of music

I was interested to know the name of the actor who read the poem at the San Diego Symphony on Sunday?