Following the completion of his Third Symphony in 1886, Camille Saint-Saëns made the following statement:

I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again.

Indeed, Symphony No. 3 in C minor takes us on an extraordinary dramatic journey which scales a mighty summit. It augments the sound world of the traditional orchestra with the addition of piano (four hands) and organ. The presence of the later is so significant that this piece is often nicknamed the “Organ Symphony.” Yet, this is a misleading label. Numerous French composers wrote works for solo organ that are titled “organ symphonies.” More appropriately, Saint-Saëns called this a Symphony “avec orgue” (with organ). A child prodigy pianist, Saint-Saëns was also one of the greatest organists of his time. Throughout the Third Symphony, the orchestra and organ blend in a tapestry of unending sonic color. The composer Charles Gounod summed this up when he wrote of Saint-Saëns, “He plays, and plays with the orchestra as he does the piano. One can say no more.”

The Third Symphony is dedicated “to the memory of Franz Liszt,” who died two months after the premiere at London’s St. James Hall. Structurally, the work continues in the tradition of Liszt’s music, with its innovative stretching and bending of symphonic form. Saint-Saëns wrote to his publisher, “You ask for the symphony: you don’t know what you ask. It will be terrifying…there will be much in the way of experiment in this terrible thing…”

Saint-Saëns set the Symphony in two large blocks which encompass and blur together the traditional four movements we would expect. The opening Adagio-Allegro moderato breaks off without a recapitulation, flowing into the serene Poco adagio. The Scherzo-like Allegro moderato-Presto which opens the second block serves as a similar introduction to the final movement (Maestoso-Allegro). Following the model of Liszt’s tone poems, Saint-Saëns wrote that he avoided “the interminable reprises and repetitions which more and more are tending to disappear from instrumental music under the influence of increasingly developed musical culture.”

Liszt and Berlioz developed the compositional technique of thematic transformation, in which a theme or motif recurs throughout a large-scale work, evolving and changing in various ways. Saint-Saëns’ Third Symphony develops in this way. In the opening bars, we can hear the motif taking shape through a series of disjointed fragments. Then, with the arrival of the Allegro moderato, it emerges fully formed (1:18). The motif, which is infused in the musical DNA of the entire piece, contains echoes of ancient liturgical chant, most notably the Dies irae (the Mass for the Dead). This is music filled with a shivering sense of ghostly mystery. There are eerie similarities to equally haunting passages from Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony. Notice the way this opening passage creates a rhythmic blur, with spirited, effervescent voices dancing around downbeats while gleefully defying them.

All of the sweeping forward motion of the Allegro moderato fades into night shadows, with a spectral dialogue between the bassoon and bass pizzicato. The organ’s first entrance emerges out of silence, ushering us into the warm, quiet serenity of the Poco adagio (10:45) and the distant, veiled key of D-flat major. The expansive theme unfolds as an intimate, prayerful chorale.

The Allegro moderato-Presto, which opens the second movement, gives us a sense of Saint-Saëns “playing with” the orchestra. It’s a ferocious and exuberant dance made up of fragments of the Symphony’s opening. The Trio section suggests the wild, chirping woodwind insanity of Berlioz with the addition of playful scales in the piano. Saint-Saëns described the sudden return of the Trio section at the end of the movement as “a struggle for mastery, ending in the defeat of the restless, diabolical element.” A celestial new theme emerges in canonic counterpoint in the strings and, in the words of the composer, “rises to the orchestral heights, and rests there as in the blue of a clear sky.”

A towering C major triad in the organ announces the beginning of the final section (Maestoso-Allegro). In a way similar to arrival of the final movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (a piece which also moves from C minor to a transcendent C major), it feels as if the entire symphonic journey has been leading to this moment. In the music which follows, all of the Symphony’s disparate threads are woven together. The first movement’s shadowy opening motif is now transformed into a majestic chorale amid shimmering, celestial arpeggios in the piano and triumphant brass fanfares. A vigorous fugue launches the Allegro into motion. It’s the kind of celebration of counterpoint that we might expect in the most dazzling organ improvisation.

Saint-Saëns’ zany zoological children’s suite, Carnival of the Animals, was written the same year as the Third Symphony. Publicly, the composer distanced himself from this lighthearted work out of concern that it would damage his “serious” reputation. Yet, in the final moments of the Third Symphony, while the organ’s mighty bass line steps down the full expanse of the C major scale, joyful ascending scales are unleashed in the strings and winds of the orchestra. In this moment, the spirit of Carnival of the Animals seems to shine through, with all of its wild fun and frivolity.

This live recording features Paavo Järvi and the Orchestre de Paris at the 2013 BBC Proms:

Five Great Recordings

- Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra (Michael Murray, organ)

- Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Berj Zamkochian, organ)

- Christoph Eschenbach and the Philadelphia Orchestra (Olivier Latry, organ)

- Paul Paray and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (Marcel Dupré, organ)

- Jean Martinon and the ORTF National Orchestra (Bernard Gavoty, organ)

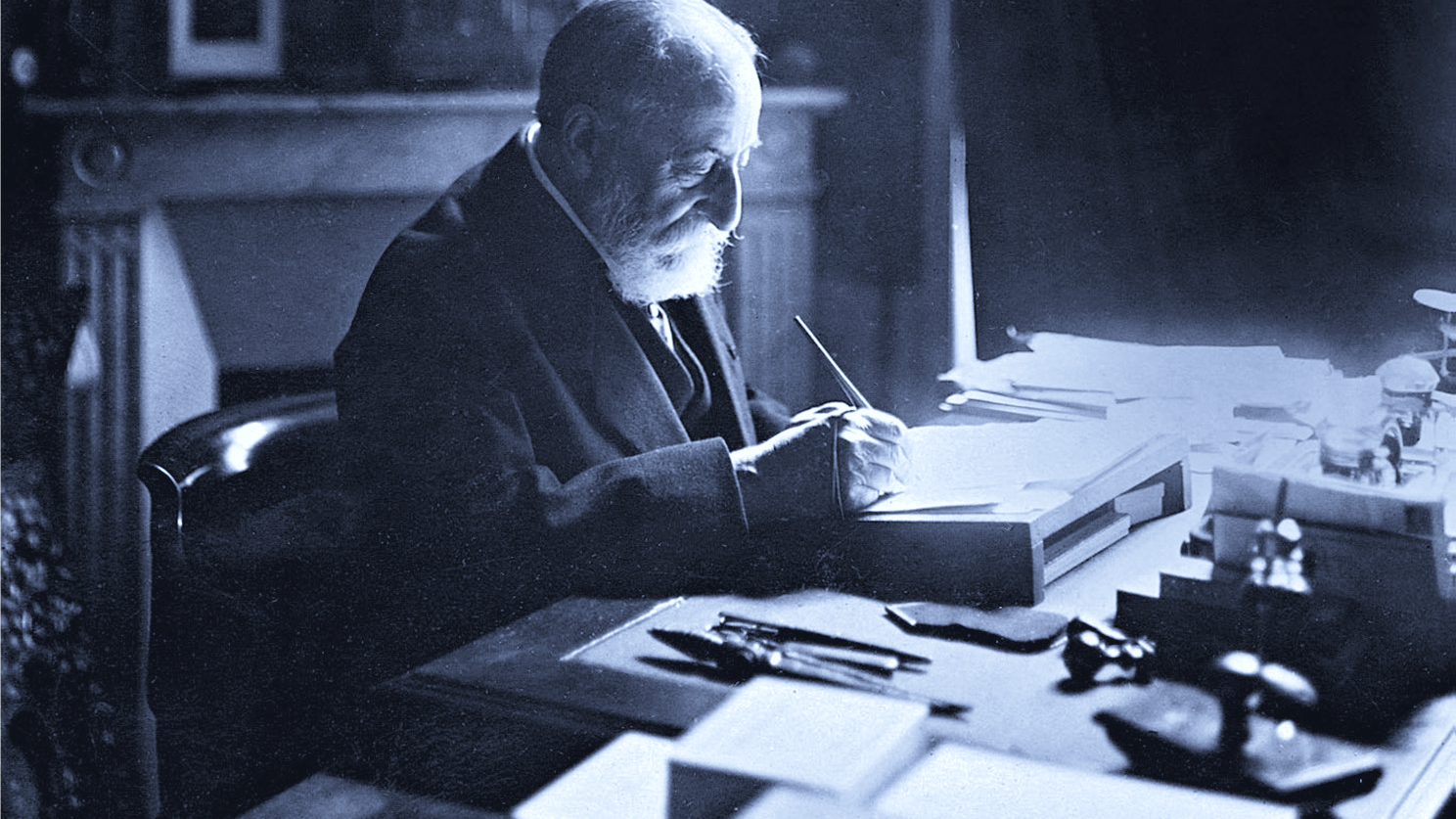

Featured Image: Camille Saint-Saëns

Hello! I’d like to introduce this work to a friend who has essentially no familiarity with classical music. I’m on a mission to find the best performance possible—the music deserves no less, and neither does my friend.

The recordings referenced here strike me as reasonably standard recommendations. I wonder, does there exist a performance that transcends others, even if it’s out of print? ~Thanks!

Hello!

I would recommend three perfomances:

– the rendition of Zubin Mehta and Perlman, the perfomance of Rozhdestvensky and the Pappano version.

For me they are outstanding. Excellent sound as well.

Carlos,

Thanks for your suggestions; I’ll give them a listen!

No mention of Francois-Xavier Roth’s period instrument orchestra Les Siecles with his father Daniel Roth on the famous organ of St. Sulpice. The lack of string vibrato makes Saint-Saens orchestration bloom into sheer delight. This is by far the best recording.

It is such a great piece! It must have been quite a triumph for him personally, to be able to feature the organ in his ‘peak’ symphony.

Don’t forget the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Charles Munch with Berj Zamkochian, organ.

The recording dates from 1958, part of the Living Stereo series, but it’s still an excellent recording… performance and sound. Boston’s Symphony Hall has some of the finest acoustics in the world and the organ there is fantastic.

I once heard the Saint-Saëns Symphony from the second row center. The pedal notes in the 2nd movement absolutely mind blowing. No volume, every thing shakes.

Also included on the disk are Debussy’s “La Mer” and Ibert’s “Escales”.

Be sure to get the remastered SACD version. I listened just the other day and it’s a fantastic disk!

I’m 68. I suppose over that time I must have been moved to tears by music. If so I can’t remember when. I am not an aficionado by any measure. So I am now moved to write that I’m glad I was alone when I listened to this. I laughed, I cried, I roared like a big-assed lion and truly I will never be the same. Imagine being able to create such work. Every note is perfect and it gets created in exactly the right time and place. And the expressions on Paavo Jarvi’s face at the end. He could barely contain. He knew they’d nailed it. Bravo

In case you wonder how I got here I watched a movie called Coffee and Cigarettes. That led me to Mahler and becoming lost to the world and Tim Judd and in turn to this moment. It is all bit of “joy of life” for me. Next up, Paris in the 1920’s, Josephine Baker and the Moulin Rouge. Heh

I second the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Charles Munch (with Berj Zamkochian, organ) on RCA.

It’s sad that more people do not appreciate classical music and will never experience this brilliant piece of music!

Well Mr Judd you fail to mention that 90% of commercial recordings play the opening incorrectly