I don’t mind telling you that I have written a tiny, tiny pianoforte concerto with a tiny, tiny wisp of a scherzo.

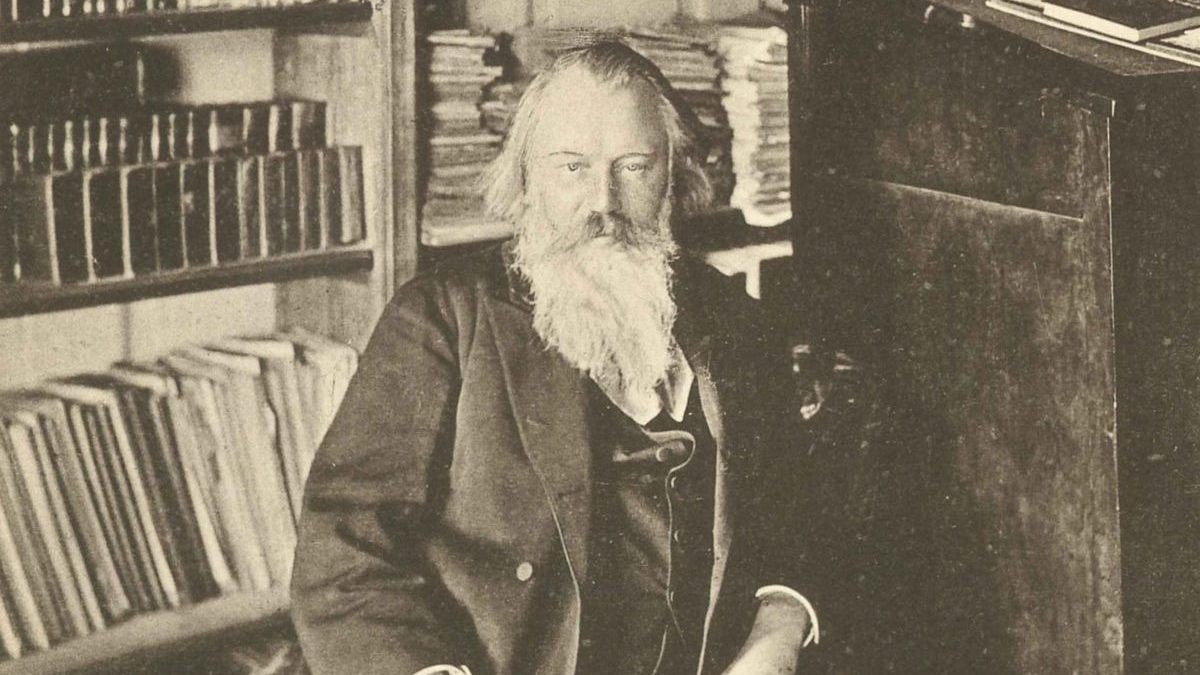

This is how Johannes Brahms jokingly described the newly completed Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major in a letter to his friend and former student, Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, dated July 7, 1881. In another letter, written around the same time, he referred flippantly to “some little piano pieces.” In fact, over the course of three years, Brahms had written a profound and monumental work which stretched the concerto form from the customary three movements to four. Arriving 22 years after the poorly received First Piano Concerto, the new piece was described by the influential Viennese critic, Eduard Hanslick, as a “symphony with piano obbligato.” Yet, for all of its dramatic weight, this is music which is intimate and autumnal. The pianist Stephen Hough has said that it is “like a massive chamber work, where the musical ideas are an exchange rather than a confrontation.”

This sense of free, conversational musical “exchange” is evident from the Concerto’s opening bars. A serene, majestic horn call emerges out of silence and is answered by a nostalgic statement in the piano. The theme is extended by the gradually awakening winds and strings. The piano springs to life, interrupting with a sudden, fiery cadenza which leads to the orchestra’s exposition. We embark on one of Brahms’ most expansive first movements. This music, worked out meticulously by a composer who described its composition as a “long terror,” unfolds with the ultimate freedom and inevitability. The final moments of the development section are infused with hushed anxiety. The recapitulation brings the ultimate repose, with the reassuring return of the horn call. The coda concludes with celebratory trills in the piano and winds, followed by a mighty final chord.

Brahms’ “tiny wisp of a scherzo” is ferocious and turbulent. Set in the tragic key of D minor, it erupts with wild passion. Long, unpredictable, irregular phrases evoke rising tension and pathos. The trio section brings a sudden move to sunny D major, with the sound of celebratory hunting horns. For a moment, we seem to have arrived in the middle of Handel’s Water Music. The opening of the Scherzo is a tempestuous conversation between the solo piano and orchestra. When this music returns following the trio, the roles are reversed, with the orchestra initiating the dialogue.

The third movement drifts into a dreamy, autumnal world. It begins with the tender, nostalgic voice of the solo cello, which is later joined by the bassoon and oboe. The cello’s achingly beautiful melody later provided the motivic kernel for Brahms’ song, Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer (“My Slumber Grows Ever More Peaceful”). This principal theme is never heard overtly in the solo piano. Instead, the piano’s entrance brings mysterious shadows which open the door to a turbulent drama. Set in a slow 6/4 meter, Brahms’ trademark cross-rhythms push and pull unpredictably. For a moment, the music floats into a hazy, distant, serene sea. It is almost hypnotic in its stasis. Then, with the return of the solo cello, we are pulled back to reality. Following adventurous harmonic wanderings, the final chord returns to the “home” key of B-flat, with a sense of quiet transcendence.

The final movement is a carefree and jubilant rondo which casts aside all of the seriousness of the previous movements. The trumpets and timpani, only heard in the Concerto’s first two movements, are noticeably absent. Heroism is replaced with playfulness and the joyful exuberance of Brahms’ Hungarian Dances.

Brahms dedicated the Second Piano Concerto to his teacher, Eduard Marxsen (1806–1887), with whom he studied at the age of seven. Marxsen, who had been a personal acquaintance of Beethoven and Schubert, influenced the young Brahms profoundly. The Concerto was premiered on November 9, 1881, with Brahms appearing as soloist with the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra. This Grammy-winning 2005 concert recording features Nelson Freire with Riccardo Chailly and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra:

I. Allegro non troppo:

II. Allegro appassionato:

III. Andante—Più adagio:

IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto:

Five Great Recordings

- Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83, Nelson Freire, Riccardo Chailly, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra deccaclassics.com

- Rudolf Serkin with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra (1966 recording)

- Claudio Arrau with Bernard Haitink and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1969 recording)

- Sviatoslav Richter and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with Erich Leinsdorf (1960 recording)

- Emmanuel Ax, Bernard Haitink, and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (2011 concert recording)

It’s the first version I heard when it came out. Still stunning! I wonder if Brahms himself would have liked it?

Other great historical recordings: Toscanini and Horowitz, Furtwängler and Fischer, Abbado and Pollini.