Johannes Brahms wrote the Four Pieces for Piano (Klavierstücke), Op. 119 during the summer of 1893 in the Upper Austrian spa town of Bad Ischl.

The brief character pieces are among the final, autumnal works of a composer who had announced his official retirement three years earlier. They inhabit an introspective world, at times filled with wistful nostalgia. The Klavierstücke, Op. 119 are preceded by three similar cycles (Op. 116, 117, and 118) which stand as the composer’s final works for piano. Perhaps the impetus for all of this music was Brahms’ deep, long standing friendship with Clara Schumann. Brahms sent the works to Clara in installments at a time when her health was deteriorating. “In these pieces I at last feel musical life stir once again in my soul,” she wrote, after playing the Op. 117 collection. A later diary entry includes the words, “It really is marvelous how things pour from him; it is wonderful how he combines passion and tenderness in the smallest of spaces.” Brahms died 11 months after Clara’s passing, in May of 1896.

The Klavierstücke, Op. 119 emerged in the sunset of Brahms’ career. Yet, they are filled with forward looking revelations. We are reminded of Arnold Schoenberg’s famous and provocative essay, Brahms the Progressive, which puts forth the thesis that Brahms, a composer usually regarded as a classicist, opened the door to innovations of the twentieth century. The opening Intermezzo in B minor (Adagio) comes as close as Brahms ever got to the dreamy impressionism of Claude Debussy. It begins with wispy, descending strands which are filled with harmonic ambiguity. In a May, 1893 letter to Clara Schumann, Brahms described the haunting and melancholy B minor Intermezzo:

I am tempted to copy out a small piano piece for you, because I would like to know how you agree with it. It is teeming with dissonances! These may [well] be correct and [can] be explained—but maybe they won’t please your palate, and now I wished, they would be less correct, but more appetizing and agreeable to your taste. The little piece is exceptionally melancholic and ‘to be played very slowly’ is not an understatement. Every bar and every note must sound like a ritard[ando], as if one wanted to suck melancholy out of each and every one, lustily and with pleasure out of these very dissonances! Good Lord, this description will [surely] awaken your desire!

The E minor Intermezzo which follows is marked, Andantino un poco agitato. Its single theme begins as a sequence of jumpy, irregular fragments. As the piece unfolds, the theme is transformed with each repetition. In the middle section, it finds sunny repose as a tender waltz-lullaby (Andantino grazioso). Following the repeat of the A section, the final bars drift off as a dreamy recollection of the waltz.

The brief third Intermezzo (Grazioso e giocoso) is a frolicking scherzo set in C major. It is a celebration of delightfully irregular phrases and hemiola (a rhythmic juxtaposition which gives us the sensation of shifting between triple and duple meter).

The Op. 119 set concludes with the boldly triumphant Rhapsody In E-flat Major (Allegro risoluto). It begins as a heroic march. The commentator, Donald G. Gíslason, has pointed out the irregularly structured “Hungarian-style 5-bar phrases” and the “amboyant gypsy-style coda.” Following a series of musical adventures, the coda moves, surprisingly, to E-flat minor, to arrive at a thrilling and suddenly tempestuous conclusion.

I. Intermezzo in B minor:

II. Intermezzo in E minor:

III. Intermezzo In C Major:

IV. Rhapsody In E-Flat Major:

Five Great Recordings

- Brahms: Four Pieces for Piano (Klavierstücke), Op. 119, Radu Lupu Amazon

- Julius Katchen (recorded between 1962 and 1966)

- Grigory Sokolov (a live recording, released in 2020)

- Murray Perahia (released in 2010)

- Nelson Freire (released in 2013)

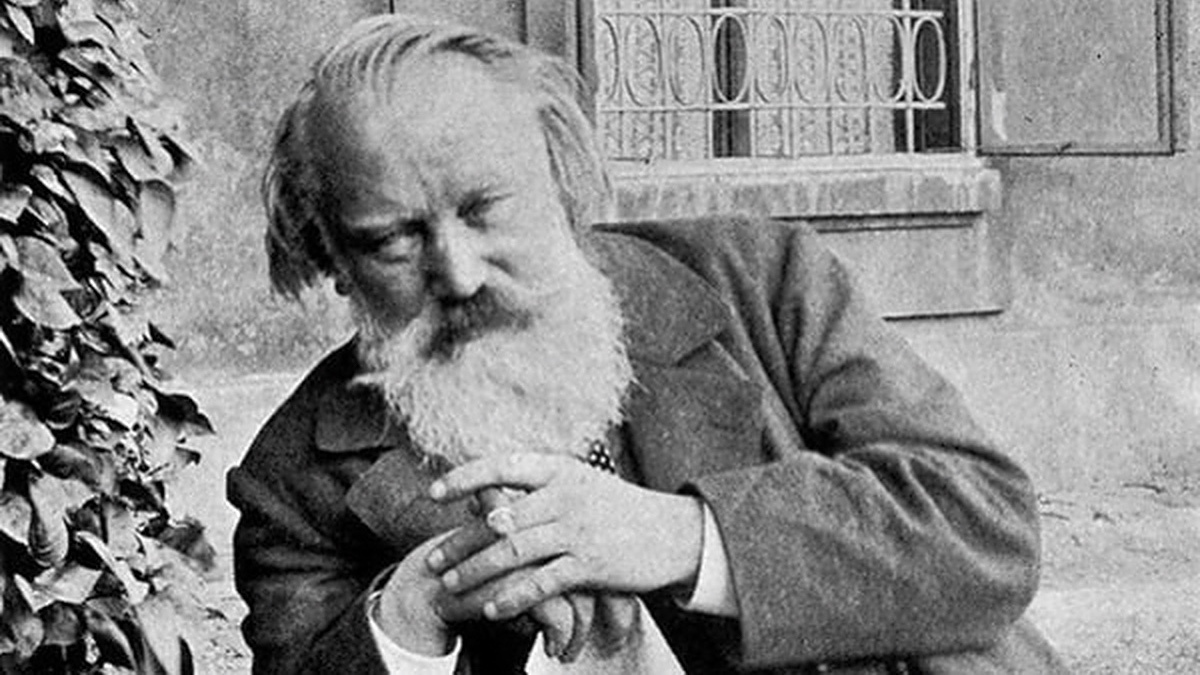

Featured Image: a photograph of Brahms taken during the summer of 1896