The introduction which opens the first movement of Mozart’s String Quartet No. 19 in C Major, K. 465 foreshadows the mystery and Romantic pathos of late Beethoven. At moments, it even flirts with the twentieth century atonality of Arnold Schoenberg.

In the first bars, the viola and two violins enter, one at a time, over a pulsating “C” in the cello. Their chromatic lines wander across a haunting and barren landscape, shrouded in harmonic ambiguity. Searching for a way forward amid mounting tension, the four hushed voices collide in wrenching dissonances. Gradually, order is established out of chaos. By the end of the introduction, darkness has receded and the exposition launches forward into the sunlight of C major.

These initial 22 measures earned the piece the nickname, the “Dissonance” Quartet. At the time of its completion in January of 1785, this music was so shocking that Mozart’s publisher is said to have returned the score to the composer under the assumption that there were multiple copying errors. Later, an irate Hungarian count accused his musicians of incompetence before shredding the score. Franz Joseph Haydn, who had yet to write his oratorio, The Creation, with its similar depiction of chaos coalescing in the purity of C major, declared, “if Mozart wrote it, he must have meant it.”

Haydn, 24 years Mozart’s senior, published the six groundbreaking Op. 33 quartets in 1781. With these revolutionary works, the string quartet matured into a drama of four equal conversing voices, rather than a virtual first violin solo with accompaniment. Inspired by Haydn’s example, Mozart set to work on the six “Haydn” Quartets (Nos. 14-19). The musicologist, Alfred Einstein, observed that, in following Haydn’s example,

Mozart did not allow himself to be overcome. This time he learned as a master from a master; he did not imitate, he yielded nothing of his own personality.

Mozart dedicated the collection to Haydn and sent him the scores, along with an affectionate letter which included the following words:

Behold here, famous man and dearest friend, my six children. They are, to be sure, the fruit of long and arduous work, yet some friends have encouraged me to assume that I shall see this work rewarded to some extent at least, and this flatters me into believing that these children shall one day offer me some comfort. You yourself, dearest friend, have shown me your approval of them during your last sojourn in this capital.

Concluding the set, String Quartet No. 19 is the sixth “child.” Beyond the first movement’s introduction, it is music filled with tenderness and sunshine. Only in the turbulent development section are there hints of darkness and lament.

In the second movement (Andante cantabile), the cello’s pulsating heartbeat returns. This time, it moves between the quartet’s voices amid a tender and passionate musical conversation.

The Minuet is the farthest thing from the simple, elegant courtly dance we might expect. It opens the door to a dramatic contrapuntal conversation in which the prevailing 3/4 meter is challenged by jarring interruptions and irregular phrases. Set in C minor, the trio section is ghostly and tempestuous, with melancholy echoes of the Minuet’s concluding bars.

The final movement (Allegro molto) is a virtuosic combination of rondo and theme and variations. It seems to pay homage to the musical humor of Haydn. Mark Steinberg, the first violinist of the Brentano Quartet, observes that

At two points the music gets stuck in a furiously repeating pattern, from which Mozart escapes simply by lifting up above a stalled note as one lifts above cloud cover to see the perennially blue skies. Just as in the opening of the piece, he escapes trouble by levitating above it. Just as the piece readies itself to say goodbye, Mozart reintroduces the chromatically yearning idea from the introduction, but now it simply teases and is tossed aside.

I. Adagio – Allegro:

II. Andante cantabile:

III. Menuetto. Allegro:

IV. Allegro molto:

Five Great Recordings

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C Major, K. 465, “Dissonance,” Hagen Quartet Amazon

- The Gewandhaus Quartet

- The Emerson String Quartet

- Alban Berg Quartet

- Quatuor Van Kuijk

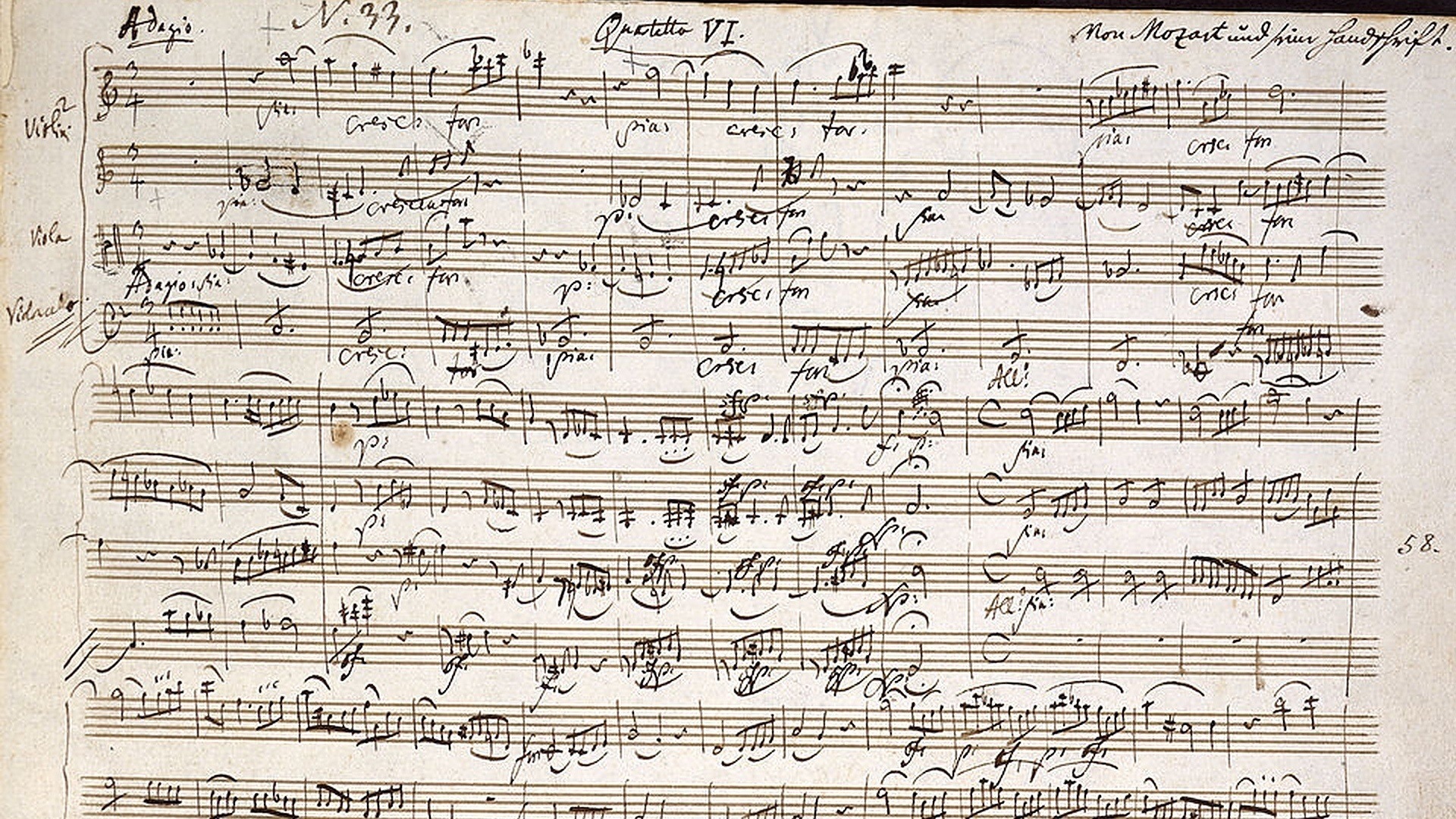

Featured Image: Mozart’s manuscript for String Quartet No. 19