“For several days, drums and trumpets in the key of C have been sounding in my mind,” wrote Robert Schumann to Felix Mendelssohn in a September, 1845 letter. “I have no idea what will come of it.”

These recurring musical reveries were the seeds of Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 in C Major, Op. 61, sketched over the course of two weeks in December of 1845, and completed a year later. As he worked, Schumann suffered bouts of depression and failing health, which included ringing in his ears. Nine years later, he would be admitted to the Endenich psychiatric asylum where he would spend his tragic final days. Schumann recalled the C major Symphony as a “souvenir of a dark period,” complaining to Mendelssohn, “I lose every melody as soon as I conceive it; my mental ear is overstrained. Everything exhausts me.”

What emerged from this inner darkness was some of the most majestic, triumphant, and life-affirming music ever written. It follows a transcendent path similar to that of Beethoven in the wake of his suicide-contemplating Heiligenstadt Testament.

Echoes of Beethoven can by heard throughout the Symphony. But another influence–one that offered a new way forward for composers daunted by Beethoven’s shadow–is even more evident. It is Schubert’s “Great” Ninth Symphony, also in C major, which remained unplayed for ten years after the composer’s death, and was finally premiered by Mendelssohn and Leipzig’s Gewandhaus Orchestra on March 21, 1839. There is also the influence of J.S. Bach, whose timeless counterpoint Robert and Clara Schumann studied together extensively, beginning nine days after their wedding in 1840. For the first time, Schumann composed away from the piano, commenting that “Not until the year 1845, when I began to conceive and work out everything in my head, did an entirely different manner of composition begin to develop.”

The first movement (Sostenuto assai- Allegro, ma non troppo) begins with a mystical trumpet call (an ascending fifth heard in octaves in the horns and trumpets), which forms the symphony’s motivic motto. Reminiscent of the opening motif of Haydn’s Symphony No. 104, it is accompanied by mysterious, hushed undercurrents in the strings. It is this motto which marks the Second Symphony’s cyclic journey, returning in the coda sections of the first, second, and third movements, and growing into a joyful and celebratory proclamation at the end of the final movement.

The exposition arrives with a first theme which is simultaneously regal and dancelike, and which is made up of obsessively repeated dotted rhythms. There is something delightfully deranged about the wildly exuberant instrumental conversations which follow. At moments, there are foreshadowings of yet-to-be-written Brahms symphonies.

As with Beethoven’s Ninth, Schumann places the Scherzo (Allegro vivace) second in the movement lineup. The scurrying and virtuosic violin lines develop organically from passages in the preceding movement (11:43). Set in duple rather than the standard triple meter, the Scherzo has two trio sections. The second trio is built on a musical cryptogram which spells the name of B-A-C-H in the German notation (B-flat-A-C-B). In 1845, just before composing the Symphony, Schumann explored the same motif in his only work for organ, the Six Fugues on the Name BACH, Op. 60.

Unfolding with expansive, longing phrases, the third movement (Adagio espressivo) is sensuous, melancholy, and hauntingly mysterious. It is filled with sudden, transcendent harmonic turns. Solo instruments, such as the oboe and clarinet, emerge to pull us deeper into this dreamy musical “story.” There are moments of pure Bach counterpoint. Nocturnal echoes of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream merge with the yet-to-be-written sonic waves of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde.

The opening bars of the final movement (Allegro molto vivace) erupt with a joyful flourish. Spirited and feisty, the winds state the main theme in the “wrong” key before being forcefully “corrected” by the full orchestra. The theme seems to be a subtle homage to the beginning of Mendelssohn’s sunny “Italian” Symphony. (It was Mendelssohn who would lead the Gewandhaus Orchestra in the premiere of the Second Symphony on November 5, 1846).

In several works, Schumann quoted the final song from Beethoven’s cycle, An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved), Op. 98. In the Symphony’s final moments, following a shadowy C minor cadence, a quote of Beethoven’s song, the title of which is Nimm sie hin denn, diese Lieder (“Accept, then, these songs”) returns. It begins as a quiet epilogue, and propels the Symphony to its triumphant conclusion. The motto which began the symphony rings out, and the “drums and trumpets” which played in Schumann’s mind are set free.

This performance, recorded on June 14, 2008, features Christoph von Dohnányi and Hamburg’s NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra:

Five Great Recordings

- David Zinman and the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra Amazon

- Wolfgang Sawallisch and the Staatskapelle Dresden

- Christoph von Dohnányi and the Cleveland Orchestra

- Leonard Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic (concert clip)

- Heinz Holliger and the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln

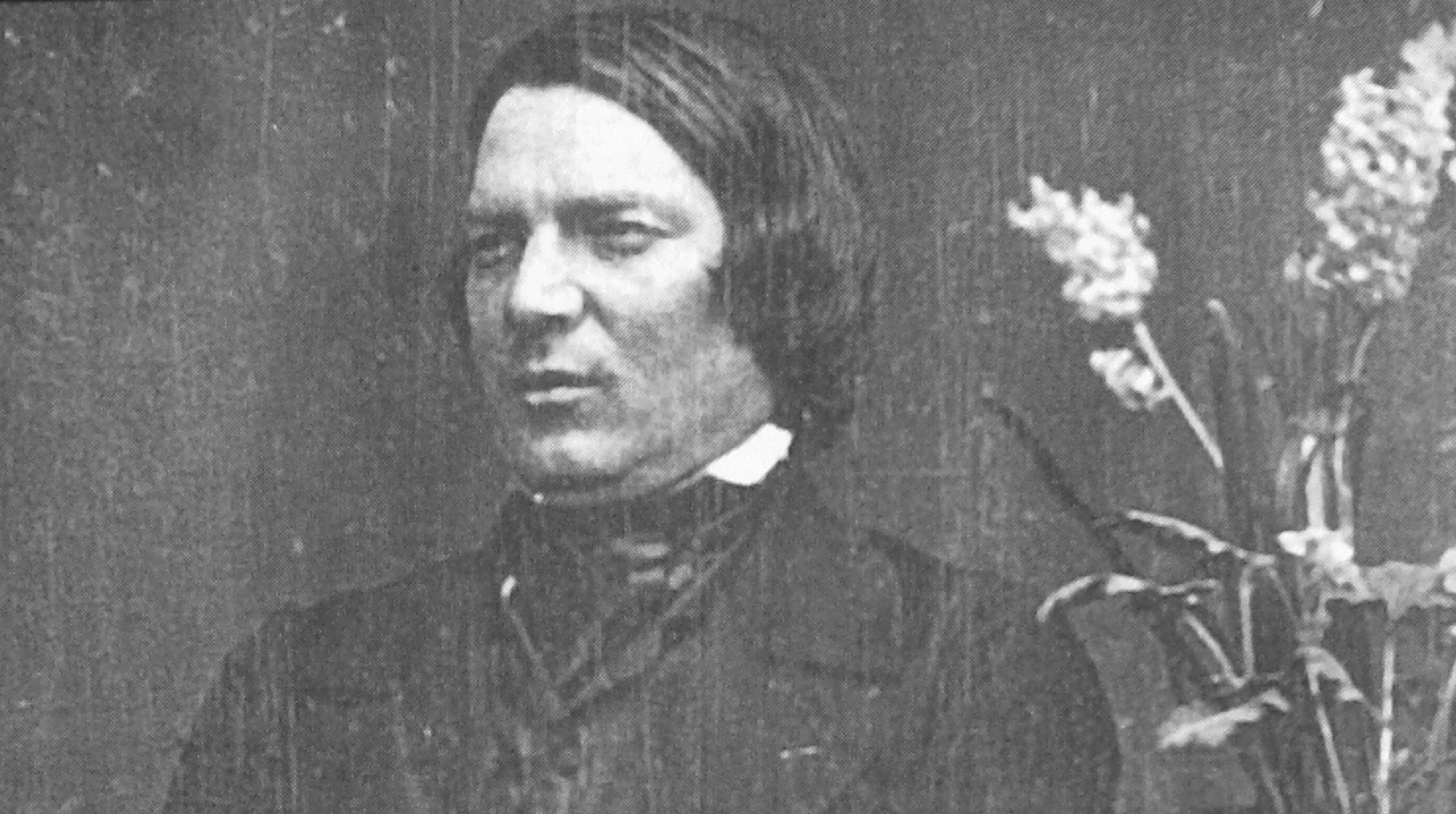

Featured Image: an early photograph of Schumann