In October, we began working our way through Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos. Today’s post continues the series. Follow these links to revisit the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Concertos.

In each of J.S. Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos, a new and distinctive cast of musical “characters” take the stage. They spring to life and converse in the thrilling drama of the concerto grosso, a popular Baroque form in which groups of solo instruments interact with the full (“grosso”) ensemble. In the Brandenburg Concertos, Bach took this form, developed by Italian composers like Vivaldi, to bold new heights.

Concerto No. 5 in D Major features the bright, virtuosic trio of violin, flute, and harpsichord. One of the most interesting aspects of this piece is the way it shatters our expectations of the traditional concerto grosso. The clearly-defined, back-and-forth dialogue between full ensemble and soloists begins to dissolve as voices break out of their expected roles with a thrilling disobedience. For example, listen to the first movement’s main theme emerging in the bass line around the 1:27 mark in the video below. Perhaps for the first time, the harpsichord leaves behind its usual role in the continuo (the “rhythm section” which provides the foundation) to also step into the solo spotlight. In the middle of the first movement, sparks of brilliant virtuosity fly as the harpsichord embarks on an extended solo cadenza. Musicologists have speculated that Bach wrote this Concerto in 1719 to show off a harpsichord built by Michael Mietke which had been newly acquired for the Köthen court.

The first movement unfolds as an exuberant drama which keeps us on the edge of our seats:

The second movement (Affettuoso) takes us to a more intimate place as the solo violin, flute, and harpsichord are heard without the full ensemble. This beautiful, lamenting melody in B minor is a kind of Italian opera aria without words. Bach quotes a theme by the French composer and organist Louis Marchand. This music may have been written for a competition in Dresden in which Bach was to have entered into an improvisational keyboard “duel” with Marchand. As the story goes, Marchand was intimidated by the prospect of going up against Bach and failed to appear.

Listen for the magical moments when the canonic counterpoint between instruments is replaced with the violin and flute singing together.

The final movement erupts with the joyful, fun-loving dance rhythm of the gigue. The movement opens with each voice entering individually and trading off in a fugue. The harpsichord seems to laughingly leap from note to note in playful ecstasy. Listen for all the delightful surprises, like the sudden, dramatic turn to B minor in the second section and the ensuing harmonic twists and turns.

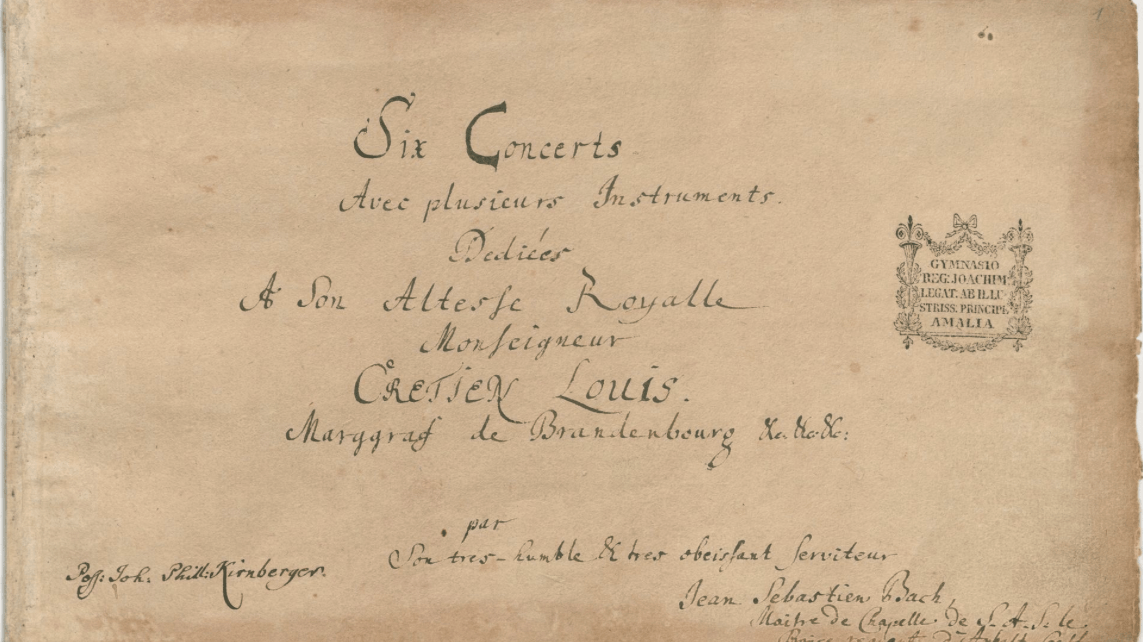

Amazingly, Bach compiled the six groundbreaking Brandenburg Concertos in 1721 as a kind of musical résumé for an unsuccessful job inquiry. Their recipient, Prince Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg, never responded and may not have opened the bundle of scores. The backstory seems inconsequential today, as this music continues to come to life for us.

Five Great Recordings

- Trevor Pinnock and the European Brandenburg Ensemble Amazon (This 2007 recording is featured, above).

- Freiburger Barockorchester (live performance)

- Glenn Gould discusses Bach and plays the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Concentus Musicus Wien

- Shunske Sato and the Netherlands Bach Society