In the final movement of Robert Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 in C Major, an unassuming but persistent motivic cell emerges which propels the Symphony towards its majestic and triumphant culmination. Around three minutes in, all of the music’s forward momentum comes to a halt on a somber C minor cadence. Then, this motive is introduced by the woodwinds. It repeats in other voices throughout the orchestra and develops into an exalted and joyful proclamation. These final moments of Schumann’s Second Symphony seem to encapsulate fully echoes of the monumental Ninth Symphonies of Beethoven and Schubert while foreshadowing the Brahms Symphonies to come.

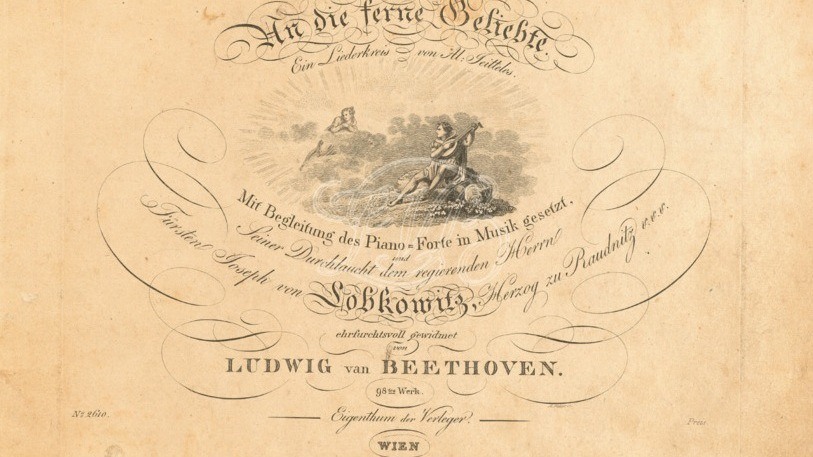

Beethoven: “An die ferne Geliebte“

Interestingly, this warm and noble motive has its origins in the sixth and final song of Beethoven’s 1816 An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved), Op. 98, which is considered to be the first true song cycle. The song’s title is “Nimm sie hin denn, diese Lieder” (“Accept, then, these songs”). A synopsis of the text, written by Alois Isidor Jeitteles, evokes love’s longing:

So he will send her the songs he has written, and she will sing them to the lute when the red of sunset falls across the blue sea and behind the distant mountain: she will sing what he has sung, artlessly, from the fullness of his heart, out of his longing, and these songs will vanquish what keeps them so far apart, and will join one loving heart to the other.

You’ll recognize the motive immediately in the introduction of the song. Here, it seems poignant and lamenting. Listen to the movement of the inner voices and the beautifully unexpected chord at 0:14:

Schumann: Fantasie in C Major, Op. 17

As it turns out, this distinct motive from Beethoven’s “Nimm sie hin denn, diese Lieder” emerges in three other Schumann works which preceded the Second Symphony. The first example comes in the first movement of Schumann’s Fantasie in C Major, Op. 17 for solo piano, completed in summer of 1836 at a time when the composer was unhappily separated from Clara Wieck, who would become his wife the following year. The opening bars of the Fantasie‘s first movement contain the famously recurring, descending four-note “Clara theme,” as well as echoes of our “longing” Beethoven motive. Dedicated to Franz Liszt, the complete Fantasie in C Major was Schumann’s contribution to fundraising efforts to build a monumental statue honoring Beethoven in Bonn.

This rhapsodic and tempestuous music embodies a full-blown Romanticism which stretches and bends classical sonata form almost to its breaking point. Like an unfolding dream, it moves erratically from one place to another. Everything seems slightly disconnected. We are pulled into the passion of the moment and everything else evaporates. In the final moments of the first movement, the full motive from Beethoven’s Nimm sie hin denn, diese Lieder emerges suddenly (10:47), melting into the “Clara theme,” and bringing with it the movement’s first real affirmation of C major. Listen to the way it is repeated with an obsessive persistence. Time seems suspended. Longing meets serene acceptance. This is music which is trying to hang on and let go, simultaneously.

Schumann: Frauen-Liebe und Leben

The “Beethoven motive” returns in the sixth song from Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben (A Woman’s Love and Life), Op. 42, written in 1840 and based on a collection of poems by Adelbert von Chamisso. The text of “Süßer Freund, du blickest mich verwundert an” (“Sweet friend, you gaze”) is a dreamy mix of blissful joy and longing. You will hear the motive in the piano around 2:45. Just as we heard in the Fantasie in C Major, it emerges with striking suddenness and disappears just as quickly.

Schumann: String Quartet No. 2 in F Major, Op. 41, No. 2

Our final example can be found in the brilliant and mercurial final movement (Allegro molto vivace) of the String Quartet No. 2 in F Major, Op. 41, No. 2, written in 1842. Here, it comes in fleeting, dolce fragments, yet the haunting presence of the motive can still be felt. Here is the complete String Quartet. The final movement begins at 16:10.

Finding Resolution in the Second Symphony

All of this brings us back to the final movement of Schumann’s Second Symphony, completed in 1846- ten years after the “Beethoven motive” found its way into the Fantasie in C Major. In Friday’s post, we’ll listen to the complete Symphony. You’ll hear the way the “Beethoven motive” emerges as an indispensable thread which opens the door to the Symphony’s majestic and triumphant resolution. A restless, recurring ghost finally finds peace.

Recordings

- Beethoven: An die ferne Geliebte, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Jörg Demus Amazon

- Schumann: Fantasie in C Major, Op. 17, Leif Ove Andsnes Amazon

- Schumann: Frauenliebe und Leben, Op. 42, Barbara Bonney, Vladimir Ashkenazy Amazon

- Schumann: String Quartet No. 2 in F Major, Op. 41, No. 2, Cherubini Quartet Amazon

I’ve been aware of several of these links for many years, but not for all of them. Thanks so much for pulling this all together!

The end of the Beethoven is also quoted blatantly in the last piece of Schumann’s Intermezzi, Op. 4.

Thank you for pointing out another example. Can you help us hear the quote by citing the timing? Here it is: https://youtu.be/JH2isllNT_Q

your blog is so great! i’ve learned so much from it and have sent others to sign up too! thank you

Thank you, Jenny! So glad you found The Listeners’ Club!