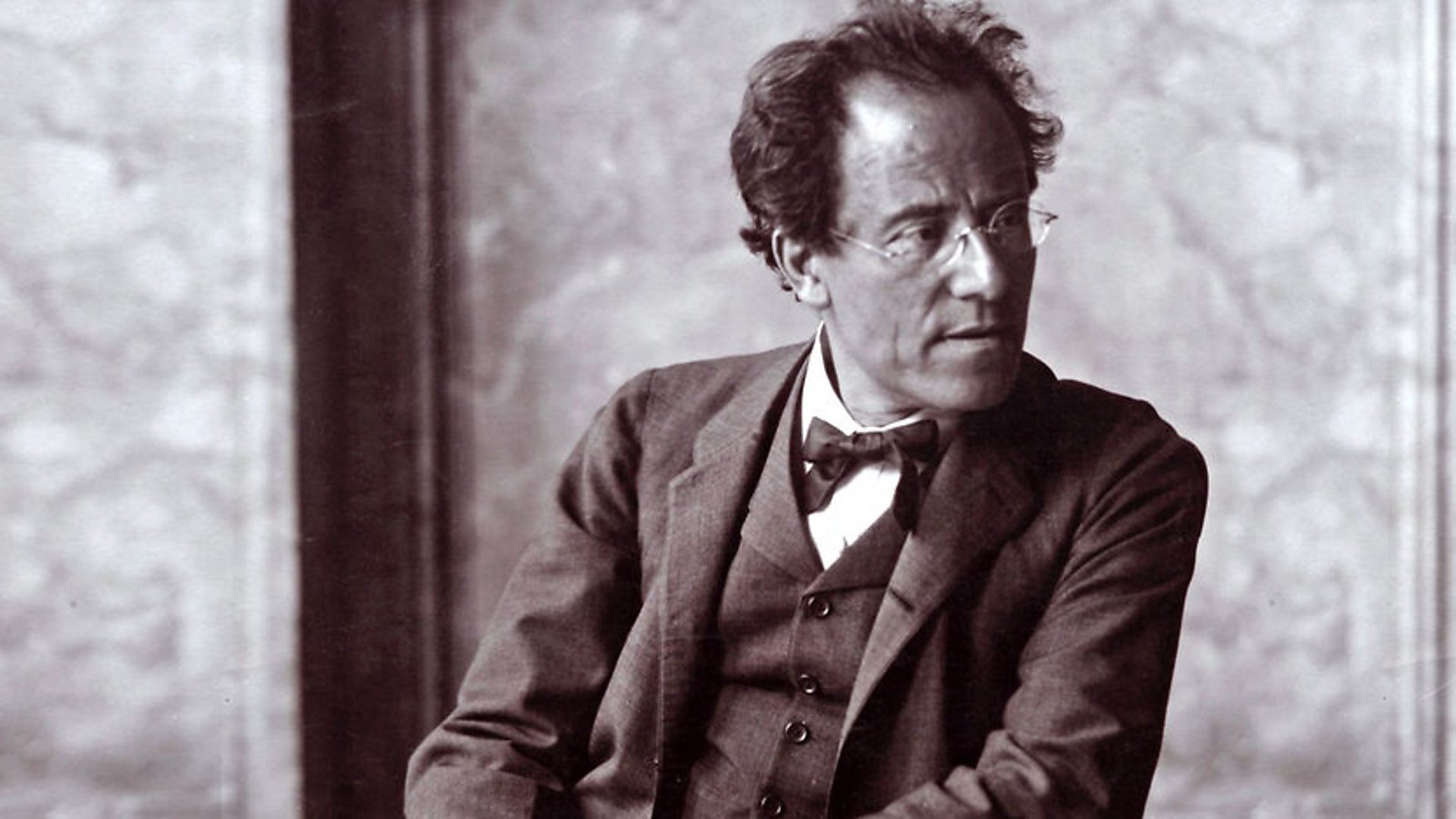

The Seventh may be the most strange and enigmatic of Gustav Mahler’s nine completed symphonies. Its five symmetrically arranged movements take us on a mysterious and haunting journey into the night. This is music that attracted the young Arnold Schoenberg, who heard the crumbling of romanticism in the Seventh Symphony’s daring and sometimes disquieting modernism. Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony, completed in 1906—a year after Mahler completed the Seventh Symphony—contains many themes built on the interval of the perfect fourth, something we hear throughout Mahler’s Seventh. Understanding the forward-looking nature of the Symphony, Mahler delayed the premiere until 1908. With anxiety, he anticipated the audience’s bewildered response.

There is something delightfully raw and disjointed about this music. It’s as if an array of previously repressed “Powers”—some familiar from Mahler’s earlier symphonies—have burst forth, suddenly and chaotically. Within the work’s progressive tonality (in this case, beginning in B minor and ending in C major), we have a sense of continuous and unpredictable modulation. Major and minor are in constant conflict. The line between darkness and light, the genuine and the ironic, the birdsongs of nature and human alienation, is razor thin.

According to Mahler, the “rhythm and character” of the Symphony’s opening came to him, suddenly, with the first stroke of the oars during a boat ride on Austria’s Wörthersee. Indeed, as with the plying of oars, the Symphony begins with an unrelenting and ominous sense of forward motion. It’s a steadily progressing funeral march. Mahler described this first movement as “a tragic night without stars or moonlight.” We can feel the darkness and foreboding in an extended solo for tenor horn, an instrument rarely used in the orchestra. A faster march (Allegro con fuoco) ushers in a series of mercurial adventures. In the middle of the first movement, we enter a new, nocturnal soundscape with the sound of echoing trumpet fanfares. An upward harp glissando opens the door to a sensuous, shimmering dreamscape. It’s a place of celestial repose, far removed from everything that came before. Yet, this scene ultimately evaporates, and we return to the haunting darkness of the opening. This time, it comes with a harsher edge. The movement concludes with a blazing march, punctuated by cymbal crashes. A glimmer of triumph is overpowered by an ultimate sense of heroic struggle.

Mahler composed the second and fourth movements during the summer of 1904, a year before the completion of the other three movements. Both are entitled, Nachtmusik (“Night Music”). This might conjure up images of soft, moonlit serenades. Yet, as Leonard Bernstein commented, something darker is afoot:

The minute we understand that the word Nachtmusik does not mean nocturne in the usual lyrical sense, but rather nightmare—that is, night music of emotion recollected in anxiety instead of tranquility—then we have the key to all this mixture of rhetoric, camp, and shadows.

The first Nachtmusik begins with two plaintive horn calls, one close and another seemingly echoing in the distance. A stiff, steadily advancing march breaks the quiet tranquillity, suggesting a kind of night “patrol.” Parallels have been made between this music and Rembrandt’s darkly veiled 1642 painting, The Night Watch. Deryck Cooke writes that this movement is filled with “the indeterminate noises of night.” We hear the sounds of nature and the bucolic clanging of cowbells. The final bars bring the searing transformation of a triad from major to minor—a terrifying motif which emerges throughout Mahler’s Sixth Symphony.

The third movement is a grotesque Scherzo, which Mahler marks Schattenhaft (“shadowy, ghost-like”). It begins with the same low grunts and groans which open the similarly ghoulish final movement of contemporary composer Christopher Rouse’s Phantasmata. The previous movement was filled with things that go bump in the night. Now, the wispy demons are here, swirling around us in a way similar to the terror of Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique, or perhaps Schubert’s Erlkönig. The musicologist José L. Pérez de Arteaga suggests that this music can be heard as “the most morbid and sarcastic mockery of the Viennese waltz.” The same sardonic voices return in the symphonies of Shostakovich.

All of the demons evaporate with the second Nachtmusik (the fourth movement). We find ourselves in the middle of a serene and intimate midnight serenade, with the magical and atmospheric addition of a guitar and mandolin. The entire movement is a work of chamber music, made up of small groups of conversing instrumental voices. In this way, it anticipates the witty, chamber-oriented pieces of later twentieth century composers such as Schoenberg and Stravinsky.

The Seventh Symphony emerges into bright daylight with the “riotous” Rondo-Finale. Boisterous timpani set the stage for a triumphant, celebratory proclamation in the brass. While many of Mahler’s previous symphonies lead to a clear moment of transfiguration, this finale plunges us into something more chaotic, outrageous, and disjointed. Fanfares, rustic dances, allusions to Italian opera, and neo-baroque fragments blend with parodies of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow. All of this turns into a vast Postmodern collage that doesn’t seem far off from the late twentieth century music of the Soviet composer, Alfred Schnittke. Postmodernism is rich in signifiers, or symbols. As the critic Michael Steinberg points out, Mahler’s reference to the third act of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger serves as “an easily recognizable symbol for a good-humored victory finale.” It’s hard to know how to take this crazy, ever-changing, ever-modulating music. Is it all humor and irony? Perhaps it enters the same jubilant world as the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its drinking song and inexplicable allusions to opera. Tricks and jokes are at the heart of this final movement. You’ll hear the “surprise” chord that lurks behind, and disrupts, a key resolution. One of these tricks even upstages the Symphony’s final resolution, ringing in our ears long afterwards.

I. Langsam-Allegro:

II. Nachtmusik (Allegro moderato):

III. Scherzo:

IV. Nachtmusik (Andante amoroso):

V. Rondo-Finale (Allegro ordinario-Allegro moderato ma energico):

Five Great Recordings

- Mahler: Symphony No. 7, Riccardo Chailly, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amazon

- Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony

- Claudio Abbado and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Pierre Boulez and the Cleveland Orchestra

- Otto Klemperer and the New Philharmonia Orchestra

The finale is one of the first Mahler movements that really captivated me. As I read more about Mahler and expanded my exposure beyond 1, 3, and 7, I learned that this was a bad movement, and didn’t follow the rules well enough. How ironic that die Meistersinger, the obvious inspiration was about breaking the rules so that Walther could win over the pedantic Beckmesser. I continue to love this work, and even got to perform it about 10 years ago on 4th horn!